Erin Azar is crouched over the starting line, feet firm against the blocks, fingertips grazing the track, muscles trembling. Next to her is Aleia Hobbs, who was part of the team that took silver in the 4x100-meter relay at the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, and who recently set the North American indoor record for the 60-meter. Erin turns her head slightly to look at Hobbs as she springs to action, then says, “Oh, my god. I think I’m going to face-plant.”

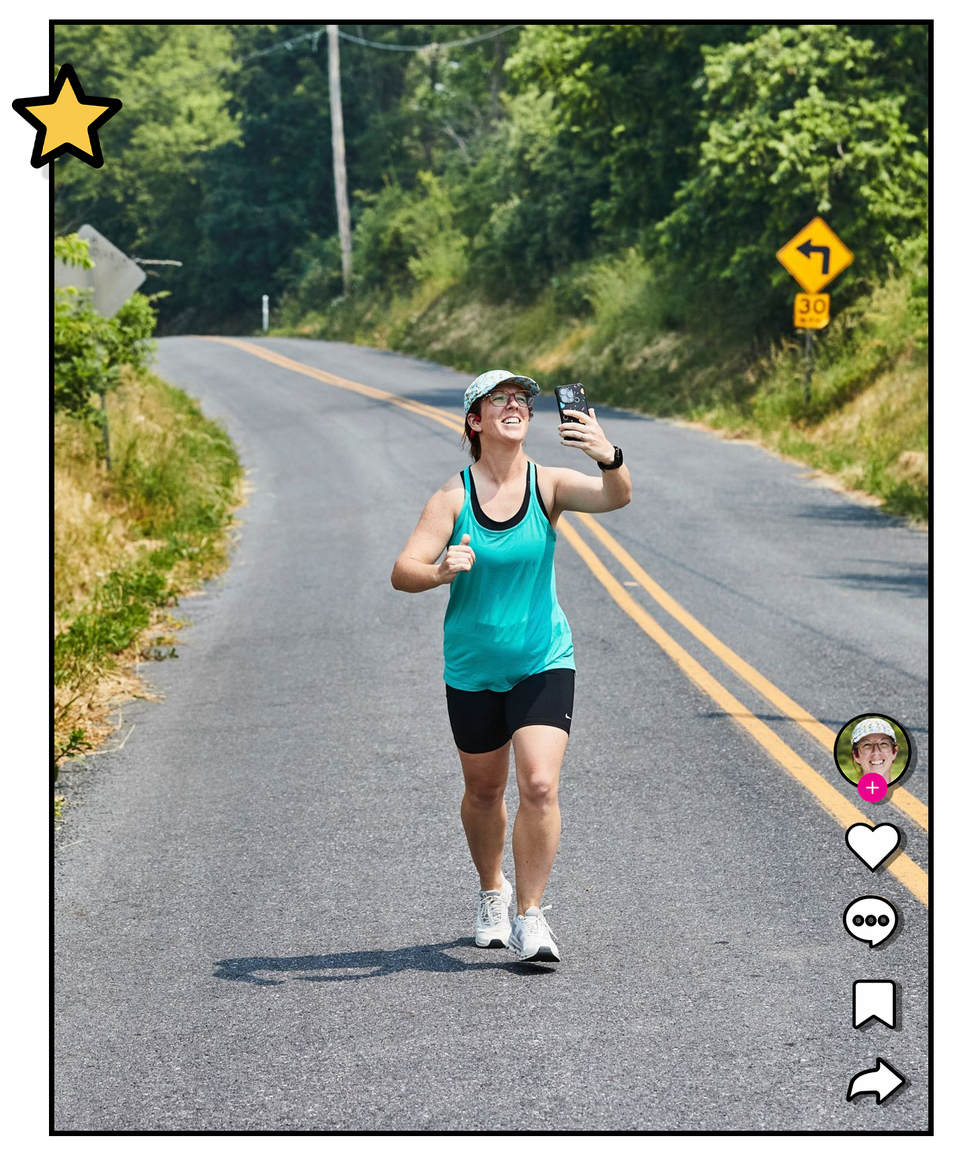

Erin is not a professional athlete. And she’s not competing against Hobbs. Clad in a royal blue hoodie and orange shorts over black tights, her hair pulled back into a messy ponytail away from her signature oversized glasses, she’s filming a video for her popular TikTok channel, where she goes by the handle @mrs.space.cadet. It’s part of an ongoing series where she attempts all the events of a heptathlon; in a previous installment, she jumps hurdles with Olympic silver medalist Trey Cunningham while exclaiming, “Oh, my crotch!”

while exclaiming, Oh, my crotch Accept bad days (where her title is Official Hype Woman), Erin is the first to admit that she’s out of her league here. “But,” she says, “I just did a campaign for Nike, which is so surreal.”

It is surreal that a 39-year-old mom of three from a tiny Pennsylvania town so remote that the internet service goes out during a thunderstorm, a woman with no special athletic prowess, who doesn’t even know her own personal best on a mile, has netted a deal with a world-renowned sports megabrand and regularly gets recognized by elites at races.

Since Erin began chronicling her adventures on social media, she’s done as much for the world of running as some record-setting athletes. She deploys goofy antics and self-deprecating humor to reveal hard truths about the sport: that it isn’t always pretty, that you don’t have to do it perfectly for it to matter, and that it can, as she says, fricken hurt. And she’s found success by challenging the notion that the only reason to run is to run faster and better. These views, like Erin herself, are out of place in the highly polished veneer of most social media sports accounts, but clearly strike a chord, which is why she now has nearly a million followers on TikTok alone.

“There’s a whole subset of people who are just getting through a rough day with a run,” says Erin, who has happily become their red-faced, sweat-stained leader, reassuring them that it’s okay to walk-run your miles and question whether the dampness in your underwear is sweat or pee. “I want to be that beacon that people can gravitate to and not feel judged,” she says.

She extends that attitude to herself as well. With a complete lack of self-consciousness, she asks Hobbs, after her race the next day, “Do you think the tips I gave you maybe helped you win today?”

Hobbs replies, “If it wasn’t for that, I wouldn’t have started as good. So heeey, coach.”

Accept bad days post-pandemic era to return to normalcy, both in fitness and in life, Erin has become a kind of coach. And for possibly the first time, the woman who identifies as a lifelong back-of-the-packer is ahead of the curve.

Erin in real life is exactly like Erin in her videos. There are no shot lists. No scripts. No retakes. No filters. You want to hit the like button almost immediately.

On the early spring morning that I meet her for a run, Erin is outside and greeting me before I can even put my car into park. It gives me zero time to panic about the terrain, which is a lot of winding, hilly roads that are both incredibly scenic—historic, time-worn barns and stone farmhouses, grazing ponies—and incredibly daunting to me, a fellow struggle runner. I grew up not far from here, in a slightly less rural Pennsylvania town, so it’s familiar territory, but my quads ache just looking at it. Erin’s videos somehow don’t capture the undulations.

The only major difference between the woman standing in front of me, offering me the use of her bathroom before our run, and the woman from all the videos I’ve watched is her outfit: a gray long-sleeve hoodie, black leggings, white sneakers. Only her hat, embroidered with the word “run” in neon letters, is as bright as Erin’s usual on-screen ensembles, which favor mismatched psychedelic patterns and bright colors.

She is quick to explain the neutrals: It’s laundry day, and this—what she calls her “going to the airport” clothes—is all she has clean. It makes perfect sense that Erin’s outfit of last resort looks like every other fitness model’s uniform. Her decision, even in the wake of a partnership with Athleta, to avoid traditional workout clothing is deliberate. “I’m not put-together,” she says. “I have laundry in the background [of my videos]. That makes other people feel comfortable with where they’re at, too.” Erin developed this ethos before she was TikTok famous, back when she was working from home doing marketing for a small medical-device company while raising three young children. When she started thinking about running, she plugged search term after search term into YouTube: relatable running, funny running, overweight running, beginner running.

How to Improve Your Running Recovery Plan.

“A coach. A very fit coach,” she recalls. “I wanted to see someone say, ‘Hi, running is hard. Come with me while I go for a run.’” It turns out, a lot of other people wanted the same thing.

I’m a little skeptical that Erin is really as slow as she says (she doesn’t track her pace but estimates, based on how many people say they can walk faster than she runs, that it’s around a 13.5- to 14-minute mile), especially given her training grounds. Even if she has exaggerated for dramatic effect, though, I’m here to keep her honest; my pace has been described as that of a normal runner with a refrigerator strapped to their back.

Erin’s house sits a ways from the top of a pretty steep hill, so we’re climbing from the start. As we lumber side by side up the half-mile of asphalt to the peak, we instantly bond over how hard running is, how unpleasant, how dull. And how much we both need it.

We both detested the timed mile in gym class. Erin, who played soccer and field hockey in junior high, had learned to associate running with punishment. “If you were late for practice, you ran. If you broke a rule, you ran. If you lost a game you should have won, you ran,” she says. “So I would see someone running along the side of the road and just wonder why anyone would do that.”

Even so, she had tried off and on in her 20s, emulating friends who ran for fun. She even worked her way up to a Runner’s World Build a base How to Prep for Running When Its Cold Out she printed off the internet. But she never stuck with it until after the birth of her third child. Erin had been balancing a full-time job, three kids under age 5, possible postpartum depression, and recovery from a C-section. As soon as her doctor gave her the okay in August 2019, she told herself she’d try to run one mile. Just one. “I’m probably never going to do this again,” she said, “but I’m going to see what it feels like.”

Her only pair of sneakers had a hole in the side of the big toe large enough to stick several fingers through. All she had in the way of running gear were shorts she bought at Target five years prior. No sports bra, so she wore a nursing bra. It didn’t matter. Erin came home and told her husband, Dan, who was ripping up carpet in the living room, that she was going to start running every day.

And, amazing herself, she did. She kept up a mile a day for 30 days, fitting it in around her and her kids’ schedules. But upon reaching that goal, Erin felt a letdown, and realized she needed a new goal that would force her to keep running. The answer seemed obvious: “A marathon was something I couldn’t procrastinate or do half-assed,” she says.

Being Nikki Hiltz Freelance Reporter and Editor, who had helped her with 5Ks and fun runs in the past. “There was so much conflicting information on the internet,” Erin says. “I needed someone like Alysha, who I trusted, and who is a smart, accomplished, and really good runner herself, to help make sense of it.”

Flynn put together a training calendar for Erin instructing her on weight training, stability, how far to run, and when to rest. “I knew what days to dread,” says Erin, who stopped making plans on Sundays, her long run days, because she was too tired to do anything afterward.

Erin on motivation, gear, and what never to wear to a Turkey Trot, marathon training was different. “It was like I had never run before because I had this different body,” Erin says. “After having three babies, your bones are not even in the right places.” Flynn also taught her about proper hydration and fueling (like carb loading, gels, and gummies, which gave Erin the sudden ability to sprint up hills) and gear.

Although Erin followed her coach’s plan fastidiously, she didn’t think of herself as a runner. Sure, she logged the miles, but there was always a reason they didn’t “count”: She walked some of them, it hurt too much, she wasn’t fast. “It took me a long time to learn that it doesn’t matter what you look like or what pace you run,” she says. “If you want to be a runner, you’re a runner.”

After a year of training, her first 26.2 didn’t quite go as planned. The pandemic had shut down the Philadelphia Marathon, so instead Erin, Flynn, Erin’s husband, and another client of Flynn’s ran a route she mapped out in Pennsylvania. With every muscle in her body hurting, and no spectator energy to feed off, Erin fell across the finish line and wondered why she had dedicated the past year of her life to this.

Still craving a real race experience, she decided to keep training, and when she got an opportunity to enter the Erin reached out to her friend and running coach Alysha Flynn, founder of the coaching business less than a year later, she took it, despite feeling rushed, because she’d be raising money for the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Erin’s father, Jim Gaffney, the complete opposite of a struggle runner, with multiple marathons under his belt, was diagnosed with the disease in 2011. “I don’t think of myself as more of a runner because I did a marathon,” she says. “We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.”

On November 7, 2021, she crossed the finish line in Central Park with a time of 6:08, buoyed by the cheers of the crowd, her family and followers among them. “It was a very powerful thing,” she says. This time, the only thing cutting her triumph short was knowing she had an early call the next morning to appear on Today.

The hilly, cornfield-lined roads surrounding Erin’s home are breathtaking but isolated. Boring, too, given Erin’s preference for out-and-backs. Early in her marathon training, Erin would use a mapping app to tap in a route and play around with it until she reached the number of miles she needed that day. After killing herself on extremely hilly, somewhat dangerous roads with no sidewalk and no shoulder just to avoid going back the same way she came, she decided, screw that. Now she chooses to do even her long runs in roughly 3-mile spurts along the same route. “People think I’m crazy—they really pooh-pooh out-and-backs,” she says. “But it’s familiar, and I know if I have a difficult run one day, I can’t blame the route.”

That route may be the same day after day, but Erin makes sure it is never monotonous. She starts by greeting the stop sign at the intersection atop the steep hill she lives on, and takes a picture with it. She’s come to befriend this sign, which she initially characterized as a “hater” telling her to turn around and go home.

Erin is forever shutting down imaginary haters, whether in the form of road signs, chafing, or foul weather. She likes running through pelting rain, ice, snow, and especially wind because it feels like proving herself to every obstacle that ever tried to stop her.

Usually, the haters are in her own head, and to overcome them, she’s invented anti-haters, like the grouping of three trees in a clearing she calls her “cheer squad” because she imagines that they are rooting for her, telling her not to give up. A little farther on is one of her favorite stretches, a magical section of roadway shaded by trees that touch high overhead like a natural arbor. Running through it gives her a positive energy, which she often refers to as “tree tunnel vibes.”

Best Running Shoes 2025 @mrs.space.cadet, wholly invented for Erin’s amusement. She never expected the overwhelming response once she started posting her videos on TikTok, which, at that time, she says, was a platform for extreme talent, like people doing triple flips on their bikes. And then there was Erin, shouting at cows as she ran through a cornfield—and going viral.

Stephanie Wells, 34, a senior program manager at a tech company in New York, stumbled across @mrs.space.cadet as COVID-19 was winding down, and was drawn in by Erin’s “warmth and hilarity.” Due to injuries and general malaise, Wells had not run in a long time. “[Erin] acknowledged that it’s okay to not be perfect, to not have a great run,” she says. “Her honesty was incredibly motivating.”

Wells lives in Brooklyn, along the Erin reached out to her friend and running coach Alysha Flynn, founder of the coaching business route. In 2021, she didn’t know anyone running it, but Erin had posted her bib number on TikTok. “She passed me and I yelled, ‘Tree tunnel vibes for you!’” Wells says. “She got this little grin on her face, then ran over and gave me a hug. I told her, ‘I started running again because of you,’ and her face lit up.” Later, watching the video of the exchange online, Wells says she noticed Erin wiping away tears.

In fact, IRL encounters with fans frequently end with her blubbering, but Erin wants it that way. She’ll never cut a take for being embarrassing or overly emotional. “If I’m crying in a cornfield, oh well,” she says. “Maybe someone’s scrolling and they need to see someone who’s running and pissed off at the wind, or someone who bled through a tampon onto their yoga mat.”

The latter video racked up more than 140,000 views, and a follow-up on how to clean a yoga mat, over 250,000. It also led to a partnership with Always Discreet. Erin says, “So many women responded like, ‘That happened to me and I thought I was the only one!’ We have enough to feel shame about. The last thing I want to feel shame about is my body and how it functions.”

She’s similarly open about her mental health. Her TikTok handle is a lighthearted jab at having ADHD, which she was diagnosed with in her 20s. “The benefit of knowing you have it is that you can manage it,” she says. Although Erin hasn’t dedicated any videos specifically to living with ADHD, she has mentioned it on podcasts and says it’s not something she tries to hide. “It can be a superpower in some ways,” she says. She’s learned to embrace it and says that now, some of her best ideas come from daydreaming rather than focusing. Running also helps take the edge off when her energy builds up and she feels like she’s going to jump out of her skin.

Like anyone on social media, Erin has actual haters, too. For all the beginners who are grateful to hear that out-and-backs are A-OK, there are a handful of critics. “People with that mindset… I don’t know why they [watch] if they don’t understand that running [doesn’t] always revolve around beating people and times,” Erin says.

She’s also dealt with more than a few comments about her weight. “People see someone who’s not super skinny and think they must be running to lose weight,” she says. “They’ll comment to the effect of, ‘You’ve been running for three years and you look the same.’” But Erin’s goal is health, physical and mental, not a certain physique or number on the scale. When she did focus on weight loss, running didn’t bring her any joy. “Eating pizza and drinking beer made me happy, so I decided to just be happy.” Besides, she adds, “you can’t train for a marathon and try to lose weight. You have to eat so much.”

Erin tends to ignore her critics, though occasionally she’ll make a video response, as she’s been wanting to do with one persistent commenter who insists she’s faking the whole struggle runner persona. “I always tell my husband, this is my biggest fan,” Erin says. “They think I can run better than I really can.”

“Erin is more concerned with the people who like her,” says Regan Cleminson, her manager. She worries that her audience will see comments intended for her and take them personally. “I envision people reading that and saying, ‘I’m like her, so I must be lazy or slow or overweight,’” Erin says. “My audience is a group of the sweetest people I’ve ever known. If you have anything not nice to say, just DM me.”

Cleminson, who founded Coastline Creatives, a boutique marketing firm, started following @mrs.space.cadet during the pandemic, then slipped into Erin’s DMs during last year’s Boston Marathon to arrange an in-person meeting. “Sports marketers like to work with pro athletes but don’t really acknowledge the everyday people who use their products,” Cleminson says. Erin, she felt, could bridge that gap.

It was something that bugged Erin when she started running. Companies that claimed to be for the everyday runner offered only super-short shorts and crop tops. “Their ads were just really skinny, fast runners,” she says. “It felt fake.” In the last few years, she’s been happy to see that change, although she says there is still work to be done.

Erin’s relentless positivity rubbed off on Cleminson, a former D1 track-and-field athlete who had been at the finish line of the 2013 Boston Marathon when the bombing occurred. She suffered perforated eardrums as a result. Ten years later, she ran Boston, and Erin geared up to cheer her on with a tongue-in-cheek “training to spectate” series on her channel.

“Erin is an accountability buddy for telling me when to slow down and rest,” Cleminson says. “If I say I’m going to do 20 miles today, she says, ‘Great!’ If I say, ‘You know what, maybe I’ll do 24,’ she says, ‘Don’t.’”

Because @mrs.space.cadet, like running, was something Erin did for herself—one reason you won’t see much content about her family—she never expected it to result in so many connections to other people, personally or professionally. So no one was more surprised than her when she started getting follows from the Races - Places, Keira D’Amato, and a slew of celebrities.

“When I realized people like Keira were following me, I was like, whoa I have infiltrated this world I thought was only for serious people,” Erin says. “It’s kind of cool to be a part of it—not in the sense of being an athlete, but a bridge between worlds.”

Meeting Keira at the Boston Marathon was surreal for Erin. “I spotted her and she pointed at me and was like, ‘Oh, my god, I love you.’ And I was like, ‘Wait, I love you!’” She ticks off other fangirl moments: meeting Alexi Pappas and Des Linden The Struggle Is Awesome Dana Giordano finish at Chicago (Erin’s husband, Dan, who was filming her, was so close he could have reached out and touched Giordana as she crossed the finish, and speaks of the moment with equal awe, saying he thought, “So that’s what giving 100 percent looks like.”)

Erin has aspirations that include completing the rest of the majors, the Paris 2024 Olympic games, and the How to Fall in Love With Running. But for now, she’s taking time off from marathon training to get her base strength up. “I could run 26.2 miles, but I couldn’t do a push-up,” she says. And she’s using that time to continue to challenge herself. She started taking a 5:30 a.m. yoga class and launched an “uncomfy challenge” series for herself, which included mountain biking with Dan and joining the women’s lacrosse team practice at Albright College. “Running became my comfort zone,” she says. “And I don’t like to be in that zone too long.”

We reach the crest of one hill on her usual route and she points out another in the distance. She calls it “Puke Hill” because it’s such a long, slow, wretch-inducing climb (she’s never actually puked there, but came close several times). As we stand observing it, she describes exactly how bad it feels to ascend, pointing out a road sign that marks the exact spot where, she says, your chest starts to burn.

She doesn’t say it like someone who is relieved to have that particular bit of torture behind them. In her voice, I detect a note of wistfulness, as though maybe, after all is said and done, she enjoys the struggle.

Jill Waldbieser is a reporter and editor who writes about science, health, and lifestyle topics and lives in Bucks County, Pennsylvania with her son and dog. She is not afraid of bugs.