Does Running Cadence Predict Injury running form comes from a guy with some serious street (or rather, road) cred. Jared Ward, the statistics whiz from Brigham Young University who finished sixth in the Olympic marathon last summer, is co-author of a new paper about the relationship among running efficiency, stride length, and cadence.

The longstanding conventional wisdom among running researchers is that whatever stride length you naturally pick is probably the “best” one for you. (Cadence, which refers to the number of steps you take per minute, is determined by your stride length at any given speed. So talking about “changing stride length” and “changing cadence” is the same thing: you can’t change one without automatically changing the other.)

There are three caveats to that conventional wisdom. The first is how you define “best.” In this case, “best” means “most efficient.” Studies over the years have found that either increasing or decreasing your cadence from your naturally selected one causes you to burn more energy to maintain the same pace. From a performance point of view, that’s bad. However, there may be other reasons to change cadence. You may be willing, for example, to accept a slightly worse efficiency if increasing your cadence reduces your injury risk in exchange.

The second caveat is the difference between short-term and long-term changes. Changing your cadence hurts your efficiency in a one-day lab test; but maybe if you increase it and then spend six months adjusting to the new motor pattern, you’d get different results. Everyone recognizes this possibility, but there’s basically no data (that I’m aware of) confirming that this happens or identifying which form changes might produce long-term efficiency gains.

The third caveat is the role of experience. If you bring a bunch of hardened runners into the lab—the type of subject who often figured into running studies 30 years ago—then it’s not surprising that they’ve naturally converged on an efficient-for-them stride. But what about inexperienced runners? Is it possible that they are much more in need of external “correction” to maximize their efficiency?

It’s this last caveat that Ward and his BYU colleagues, including veteran biomechanics researcher Iain Hunter, decided to investigate. The All About 75 Hard All About the Run/Walk Method (and an accompanying press release is here).

They tested 19 experienced runners, many of whom were competitive college runners, and all of whom averaged at least 20 miles per week over the preceding two years. They also tested 14 “inexperienced” runners, who reported never having run more than 5 miles in a single week in their lives (which seems amazing to me, but maybe that’s just a reflection of the people I hang around with).

Each runner’s energy consumption was measured (via the proxy of oxygen consumption) at a self-selected pace and cadence. Then they were measured again with stride lengths shortened and lengthened by 8 and 16 percent, by running to the beat of a metronome, for a total of five data points.

Join Runner's World+ for unlimited access to the best training tips for runners

The basic finding was that both the inexperienced and experienced runners burned the least energy at their preferred stride, and got less efficient when they either increased or decreased their cadence. There was no apparent difference, within the ability of the relatively small study to detect it, in how far the inexperienced and experienced runners deviated from their “optimal” stride.

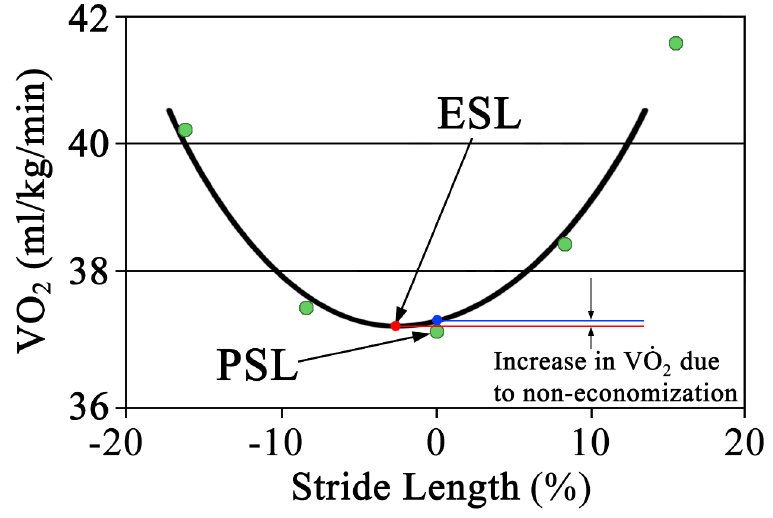

Here’s some sample data, showing how oxygen use varied with stride length:

In this figure, PSL is the “preferred stride length” the runner naturally selected. ESL is the “economical stride length” that produces the lowest oxygen use when a polynomial curve is fit to the data. On average, the PSL resulted in 1.2 percent more oxygen use than the ESL in the experienced runners, and 1.8 percent more in the inexperienced runners. This difference was not statistically significant: The smallest difference they could reliably detect was calculated to be 2.73 percent.

For the most part, the curves were fairly symmetric, but in some runners the curves were steeper for increasing stride length than for decreasing stride length. That means these runners could afford to shorten their stride (and thus increase cadence) while paying a minimal penalty in extra energy burned. Given that increasing cadence is often suggested as a way of reducing impact forces for runners who get injured a lot, this is worth keeping in mind. If you think you’re overstriding, you may be able to boost your cadence without sacrificing much efficiency, even in the short term.

RELATED: How I Broke a 3:30 Marathon After a Long Break?

All About 75 Hard a longstanding debate about how, exactly, we optimize our movements. Do runners learn efficient strides through experience, or are we naturally wired to move in energy-efficient ways? The new results argue for the latter—though, it should be noted, other researchers have reached exactly the opposite conclusion.

That debate will carry on. But for now, Ward sees the new results as evidence that trying to tweak your form to achieve some sort of smooth, beautiful, and energy-efficient perfect stride is misguided. As he put it in the press release: “Enjoy running and worry less about what things look like.”

Speaking of “what things look like,” when we asked Boston Marathon veterans for their course tips for Ward in his first Boston, most didn’t realize they were looking at the guy who placed sixth in the Olympics.

***

Discuss this post on the Sweat Science Facebook page or on Twitter, get the latest posts via email digest, All About 75 Hard Advertisement - Continue Reading Below!