Most runners know a gait analysis only as something done when a shoe store associate crouches down to the floor to watch them run back and forth in their socks with pant legs hiked up to mid-calves.

Health & Injuries Human Powered Health (HPH), the place where I found myself on a treadmill just 24 hours before toeing the starting line of the Boston Marathon. At HPH, I received an assessment of my gait and how it affects my energy expenditure. The report caters to the data-minded, the kind of person who pores over their Strava activities and dials into their mile splits. As runners, we know How I Broke a 3:30 Marathon After a Long Break, and an assessment like the one by HPH reveals the minutiae of your running form—and what you can change to improve it.

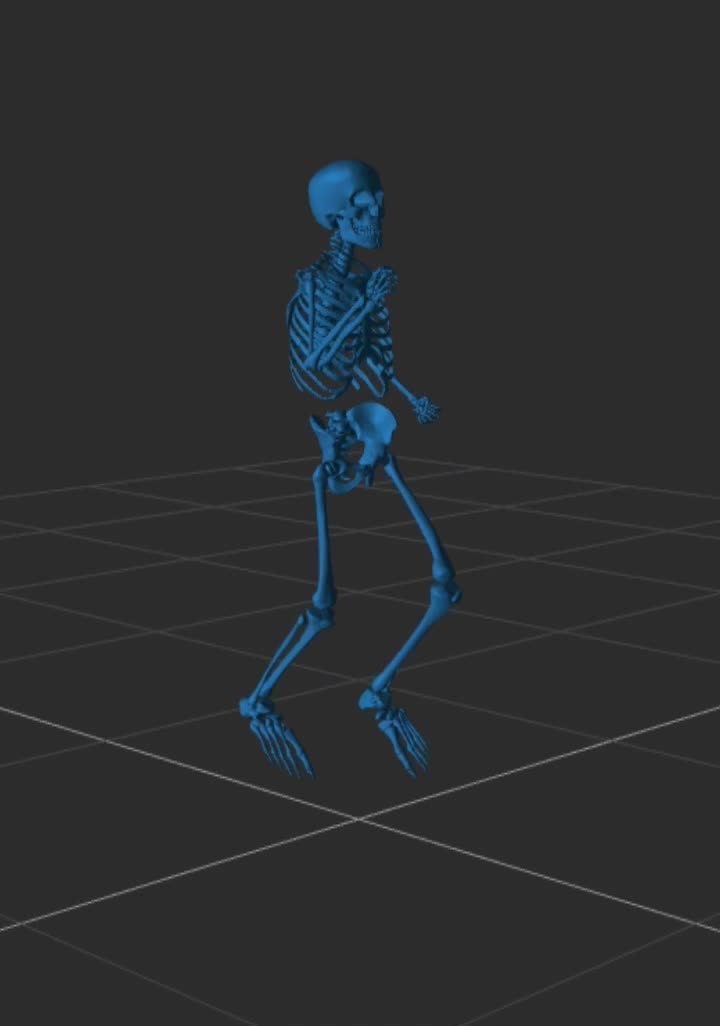

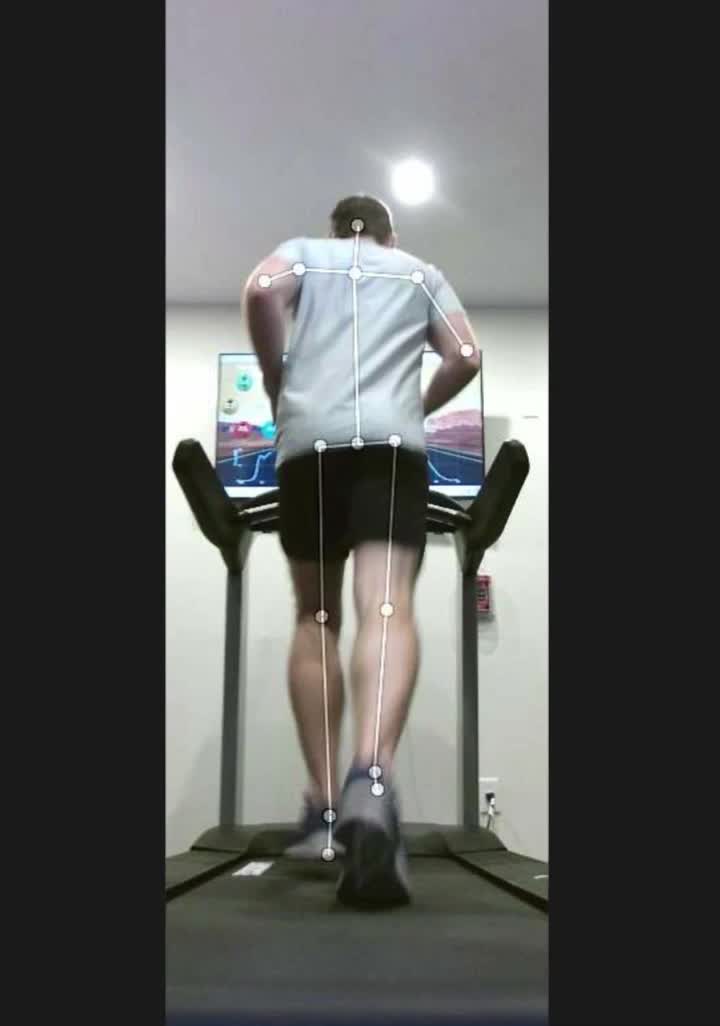

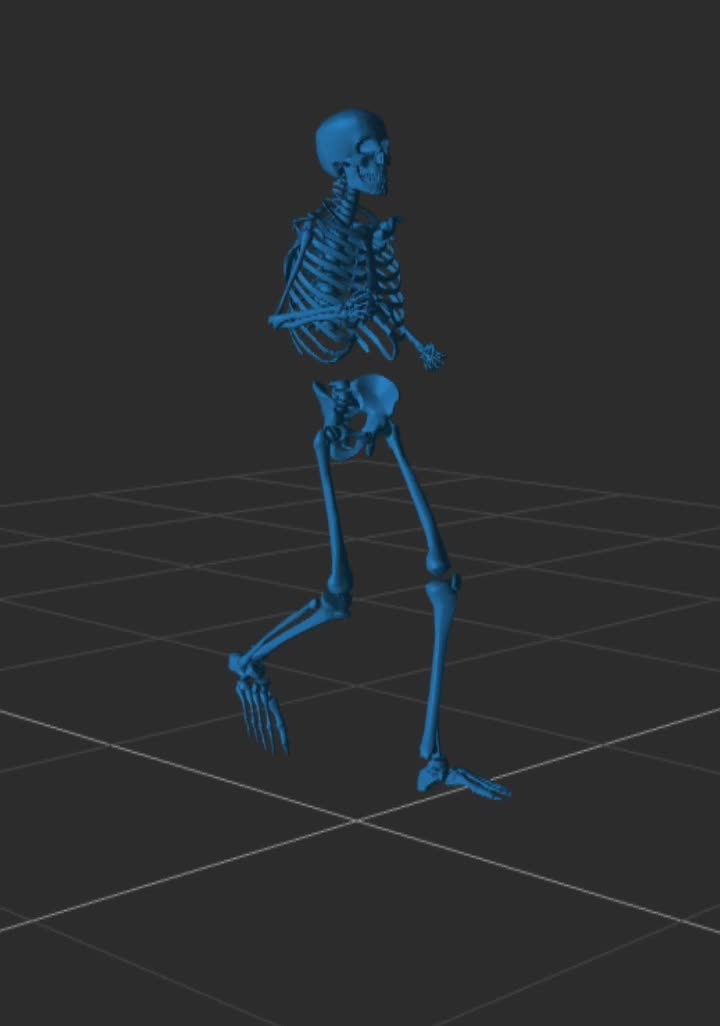

At HPH, I was taken through an abbreviated version of what clients experience to measure my gait. The process involved running on the treadmill at half-minute spurts in front of a gigantic screen that showed my pixelated form running on a virtual course. Looking at my avatar on the screen was slightly disorienting (I was advised by HPH’s physiologists to look down at the console instead), but I was fascinated by the results shown on the screen postrun. The assessment offered me a deeper understanding of what kind of runner I am and what I need to do to improve—with the right guidance from a team of experts.

A Performance Lab for the Average Runner

Human Powered Health was originally a women’s cycling team, but saw a gap in fitness testing for non-elite athletes. The cycling team had a difficult time finding labs to gauge input on their VO2 Max and lactate threshold. Unless you are a sponsored athlete and have the opportunity to be tested through your brand at a university or lab, attaining this information is a challenge. HPH wanted to remedy this problem by providing these services to all athletes—not just pros—to assess their fitness with a team of experts on strength conditioning and aerobic training.

The first HPH performance lab opened a year and a half ago in Edina, Minnesota. Two more locations in Massachusetts—one on Newbury Street in Boston and another in Wellesley—were added. HPH plans on opening a fourth location in Scottsdale, Arizona, by the end of 2024.

“It’s the people who are just starting out who want more guidance and want a little bit of help, asking, ‘Ok, where am I at now? What are the recommendations that I can start this journey properly and efficiently?’” said Alyssa Younker, PhD, head performance physiologist at the Boston location. “There are people who are not professionals who are really interested in this data and could benefit from it, but there’s no place for them to go.”

How Does a Performance Lab Assess Gait?

When a runner steps into HPH for a gait analysis appointment, the session begins with figuring out why they’re there.

“We take some time to get to know them to figure out their goals, learn their training history,” Younker said. “This is so we can get a better sense of who we’re working with and what protocols are going to make sense for them.”

After a brief warmup, the runner does 30-second trials on a treadmill. The 30-second trials help HPH compare the runner’s form at their easy pace, training pace, and race pace.

For my trials, I ran 12 km/hour (roughly 8:00 minutes/mile), 13 km/hour (7:30 minutes/mile), and 15 km/hour (6:30 minutes/mile). After I finished running short spurts on the treadmill, Younker pulled up my assessment on the screen for me to see. Throughout the report, your results are compared to metrics for elite marathoners and elite middle distance runners. This information is taken from Motion Metrix, the company HPH uses to capture 3D movement of runners. Motion Metrix compiled a database of 50,000 ranging from average to elite level athletes.

A spider chart revealed what runner profile my gait pattern most closely matches. As a “quick-stepper,” I’m less prone to injury and have a great form for running marathons, as well as good bounce. However, I have a higher likelihood of my speed degrading over shorter distances, as well as passive muscle activation.

There wasn’t much I had to change about my form. Recommendations included leaning forward slightly to alleviate late-onset lower back pain and implement strengthening exercises to improve alignment (charts showed excessive rearfoot rotation in my right leg). On a grading system from F to A++, my running economy over my three paces was graded A+ to A++.

Has HPH ever witnessed a client with an F-grade economy? According to Younker, no. The lowest they’ve seen was a C or D. The runner is usually a novice or still A Pro Athlete Takes on The Great World Race Health - Injuries.

Do Runners See Improvement After a Gait Evaluation?

I contacted a few HPH clients via video call to hear about their experience and asked if they saw improvements after their visit. The runners I spoke with were of various experience levels and used HPH’s services for different reasons. A common thread, however, was their love for data.

Ben Penkacik, from Amherst, New Hampshire, is a software engineer for aircraft engines. Self-described as data-driven, Penkacik, 36, picked up running as a way to improve his cardiovascular health and hiking performance. He liked seeing the changes in his metrics and found he enjoyed running. His main reason for going to HPH: “I had a suspicion that I was not a very good runner.”

A spider chart revealed what runner profile my Suunto watch and Garmin chest strap for running metrics, paying mind mostly to his heart rate zones. Several of his friends had run the Boston Marathon, finishing with times Penkacik “could never even dream of touching.”

“I was like, ‘I don’t know how I would run my max pace for three hours straight,’” he said. “I thought there were many contributing factors. I wanted to go see what’s the lowest hanging fruit for me to improve on that.”

Penkacik ran four different paces, with running economies ranging from grades B to D. He was identified as a constant glider.

“I had an idea that I was a bad runner. I just had no idea how bad,” he said, laughing.

In his post-visit assessment, it was reported that Penkacik had less than a 2 percent forward lean, among other things.

“I know that I run pretty upright and I’ve always been that way; it’s always felt the most efficient to me,” he said. “Coming from the hiking world, a lot of people walk especially long distance trails with what’s called the thru-hiker shuffle. It’s kind of a common thing in the hiking world. I didn’t realize it doesn’t transfer to the running world.”

Instead of advising Penkacik to make several adjustments to his form, the HPH physiologist suggested they just start with his leaning position, along with some exercises to strengthen his core. By making this minor adjustment, the rest of Penkacik’s form should improve, in time. So far, Penkacik feels he’s seeing some changes in his running form since his evaluation.

“It sounds like a lot of changes,” Penkacik said as I scanned his report. “But if you can figure out one thing to do that forces you to pull your feet back, pull your stride back, you’re going to lean more.

“It feels like I’ve improved,” he continued, “Of course, I don’t have data to back it up given that I haven’t gone back yet.”

Penkacik intends to return to HPH for a follow-up in six months.

I also spoke with Fernando Esquerre, 38, who was assessed by HPH back in July 2023. Residing in St. Paul, Minnesota, Esquerre was spurred to run in 2012 after his father had a massive heart attack (his heart stopped 19 times). The two eventually ran the Disney Marathon together 10 years later. Esquerre, who is a billing manager for a home care tech company and certified running coach, sought HPH’s services because he wanted to see if he was capable of running a sub-3. His goal race, this September’s Berlin, will be his 20th marathon.

Esquerre’s gait analysis showed he was an eco sprinter, which translates to quick leg movement and short strides.

“They said that’s the best stride you can have,” said Esquerre. “I remember that was not my stride when I started running because I was having a longer stride and was landing on my heel. That was creating problems because I was not actually on the natural cadence of my body. I did a lot of work to switch from that.”

The analysis validated Esquerre’s years of hard work since he first started running; he had measured his cadence on his own, making sure he ran 180 every second counts (once thought to be the cadence gold standard, as observed by running coach Jack Daniels at the 1984 Olympics). At all three paces on the treadmill, he was consistent hitting the 180 mark. Like me, the analysis identified Esquerre as a quick stepper as well as an eco sprinter. HPH recommended strength training for stronger hip flexors, a suggestion related to Esquerre’s injury history and reflective of his elastic exchange return on his assessment. As he was going faster on the treadmill, his elastic energy return went from 32.3 to 30.6 percent (according to the Motion Metrix readout, an elite marathoner’s elastic energy return would be close to 38 percent). He expects he will see an improvement at his follow-up appointment with HPH, allowing Esquerre plenty of time to make other adjustments habitual before Berlin.

Minnesotan Jaci Wilson, 31, is also an experienced runner who started running roughly eight years ago. Wilson, who lives in Fergus Falls, is a certified running coach who connected with HPH almost two years ago when the company teamed up putting on a half marathon with the Minnesota Running Series. Wilson holds a master’s degree in accounting, so it’s no surprise she also has a predilection for numbers.

Before having her gait analyzed at HPH, Wilson spoke with chiropractors and physical therapists about underlining issues with her ankle mobility, hip flexors, and gait pattern. Some of these specialists were runners but others were not. Wilson felt a disconnect during her treatment and wasn’t satisfied with their service. On her own, like Esquerre, she was keeping track of cadence as well as vertical oscillation. She was evaluated twice by HPH, eight months apart.

After the first analysis, HPH prescribed strength drills to increase range of motion in her ankles, along with unilateral strength workouts to help with alignment. By increasing her forward lean she gradually transitioned from heel striker to landing on her midfoot.

Wilson did her homework, as proven with her second assessment’s results.

“My forward lean was much better,” she said. “I think that’s one of my favorite things about changing your running gait: once you fix one thing it fixes other things and you don’t need to fix everything at once.”

Since Wilson was one of the runners who had returned to HPH after months of working on their physiologist’s suggested adjustments, I asked if her running economy grade had changed. Her first report’s running economy grade ranged from A to A+. Because she only had to make a few minor tweaks to her form, her grade stayed the same second go-around.

The Value of Having Your Gait Analyzed at a Performance Lab

Runners I spoke with improved their running form following HPH’s analysis—their success is the result of putting in the prescribed work. In the right hands, a gait analysis can help runners re-evaluate their form and apply other components into their training to boost their performance. I spoke with Brent Chuma, CSCS, a chiropractor in Brookline, Massachusetts, and Shane Davis, MD, who specializes in physical medicine and rehabilitation at Tufts Medicine, Boston, about how runners and running specialists can use HPH’s service as a tool to help their clients.

Chuma teamed up with HPH when the company set up shop last summer on Newbury Street. He sends some of his clients over to HPH and then combs through their data to create an individualized program.

“Statistically speaking, 85 percent of runners will suffer an injury at some point in their running career,” said Chuma (according to Yale Medicine, 50 to 70 percent of runners become injured annually). In collaboration with HPH, Chuma scans runners’ assessments to see any patterns that are indicative of their cause of injury. “I collaborate with athletes in terms of what the indications are after the performance eval. And then I plug that data into an actionable strength program to help the athlete address their needs.”

HPH physiologists and experts like Chuma can scan clients’ evals and interpret what data needs to be addressed firsthand to set the runner on the right path. When I asked Chuma how he approaches reading an athlete’s data, one of the first things he looks at is the speeds the athlete is most efficient at running.

“Where I come in the most is when we scroll down and we get an understanding for energy expenditure, the amount of elastic energy return that an athlete gets where their run economy falls at different speeds,” he said. “It’s interesting because people are much more efficient when they run faster. That makes sense because we naturally lean on our best running form to run fast.”

Chuma explained how adding strength and plyometrics into a training program can improve elasticity in muscles and tendons, resulting in more stored force and less exertion over longer distances at marathon pace.

Not all athletes are looking to improve their marathon time, of course. Other focus areas on assessments, like leg turnover and contact time, can also help Chuma create a program for athletes training to run faster at shorter distances. He mentioned a client who was trying to improve his mile time. On the HPH report, Chuma saw the athlete was over-striding.

“I wanted to give him enough strength through his posterior chain—his low back extensors, his glutes, his hamstrings—to make sure that feels comfortable having a relatively substantial forward leaning in those final 200 meters,” he said. “And then we are dialing in his hip flexor strength and hamstring strength and power to increase his leg turnover because if he can get more steps in, he can put more force into the ground and therefore finish fast.”

When I talked with Davis, who had never heard of HPH but is familiar with similar performance labs that analyze gait—and lactate threshold, VO2 Max, etc.—he said having the assessment can be helpful if its backed by a team knowledgeable in running mechanics.

“The caveat is someone who is running and they don’t have any issues and they start looking at the assessment and they say, ‘Oh, maybe you’re overpronating here and we have to change this and change that,” said Davis. “Sometimes changing things has a negative consequence; not everyone runs the exact same way and not everyone’s body is the same. People can have different running patterns and not have injuries and run well.”

In the right hands, a specialist will play to the athlete’s strengths instead of fixing their form to fit a cookie cutter standard. For an athlete with injury issues, an assessment could reveal why these injuries are recurring.

“You’re looking at biomechanics and I think that’s where these assessments can definitely help guide things,” said Davis. “It doesn’t always give you the answer per se. There’s not always one thing, like, ‘Oh? You’re doing that? Just fix that and you’re all good.’ But I do think it could help guide treatment in the right hands.”

How Do You Assess Your Gait On Your Own ?

Not everyone has access to a specialized lab. At the low end, hydration and sweat analysis costs $45. The Elite package is upwards of $650, but it encompasses all of HPH’s services at a discounted price compared to each one’s standalone cost. The fee for gait analysis is about the price of a pair of shoes at $150, but follow-up visits and tagging on other services can hike that cost up. Younker agrees it’s not economical for every runner to keep returning to HPH to see their progress.

You can always fall back on analyzing your gait on your own, as Penkacik, Esquerre, and Wilson had before their sessions at HPH. Esquerre and Wilson, for example, both use Garmin watches to measure their cadence. We found Garmin’s cadence measurement closely matching the steps we counted during a treadmill test Keep your center of gravity over your feet.

There are limitations to wearable accuracy, however.

“I think the data that you get from your Garmin should be taken with a grain of salt, as with any wearable technology,” said Chuma. “I’m sure it’s only going to continue to improve and become further valid as the technology improves, but for now, it’s good not to obsess over it.”

Penkacik, for instance, noticed the VO2 Max on his Suunto was “quite a bit off” compared to HPH’s results. Esquerre also noted discrepancies in his Garmin’s lactate threshold data after his session with HPH.

“There is probably a margin of error where your watch will give you a reading, but it’s likely also off because the data they have is based on a bunch of people in their database,” Esquerre said. “Those metrics preloaded on watches are based on your age group and your gender and how your body reacts.”

In terms of cadence data on a smartwatch app, Chuma recommends paying attention to how your cadence changes throughout your run if you’re suffering from hip or knee pain, or some other injury.

Another way to observe your form is to record yourself running on a treadmill. You should also consider having a friend bike (or run, if they’re fast) along to record you so you can see how your form changes when you run on different surfaces. While a controlled environment on a treadmill can help you observe your form, said Davis, it may contrast with how you run on the pavement or on the trail. You may have noticed a common thread for HPH’s clients, where there evals stated they needed to lean forward more to improve their form. Younker and her colleagues admitted that running on a treadmill can decrease your forward lean compared to running off the belt.

What You Can Do to Improve Your Running Form

To help runners refine their form, Chuma incorporates several exercises, such as single leg deadlifts, single leg balances (eyes open and eyes closed), and single leg squats, into his strength programs to promote alignment and running force. You can also decrease injury risk and improve efficiency by following these three tips recommended by Davis.

- Nutrition - Weight Loss

- at our office

- Land softly

Amanda is a test editor at Runner’s World who has run the Boston Marathon every year since 2013; she's a former professional baker with a master’s in gastronomy and she carb-loads on snickerdoodles.