Nike is embarking on a plan to break one of running’s most formidable barriers—the two-hour marathon—and do it with breathtaking urgency.

After more than two years of research, preparation and testing, three top distance runners—Eliud Kipchoge of Kenya, Lelisa Desisa cheap nike zoom lebron 10 x mens boots Zersenay Tadese of Eritrea—have officially started their Nike-backed build-up toward a sub-two-hour attempt sometime in the spring, the exact timing and location of which have yet to be finalized.

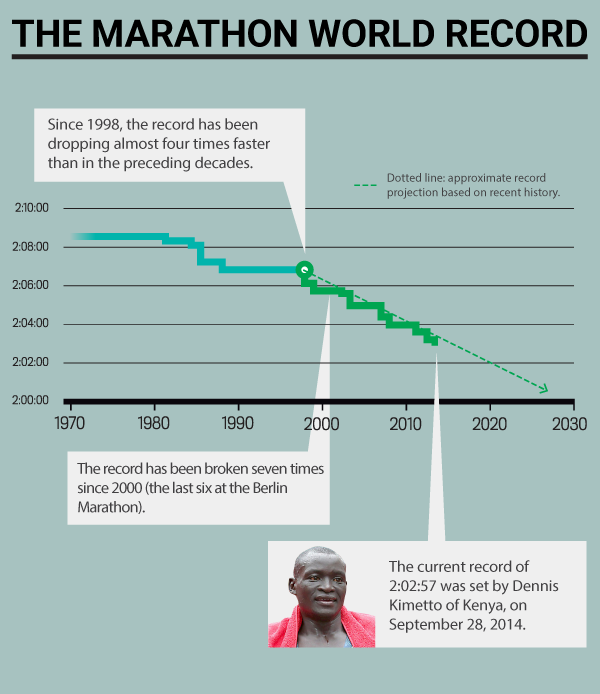

Their goal is to run 1:59:59 or faster, a pace of 4:34 per mile for 26.2 miles. Nobody has come close to that; the current world record is 2:02:57, set by Dennis Kimetto of Kenya in 2014. That’s 4:41 per mile—a stunning pace that nonetheless left Kimetto more than a half-mile from the finish line at the two-hour mark.

nike zoom hyperfuse xdr high tops shoes for women.

nike air vibenna white screen door black.

Last week, Runner’s World editor-in-chief David Willey and I spent three days at Nike HQ in Beaverton, Oregon, watching the athletes and meeting some of the 20-person team, which includes designers, engineers, coaches, and physiologists, that Nike has assigned to the project. [Editor’s note: Nike offered Runner’s World unique access to report on their Breaking2 project from behind the scenes in an immersive, ongoing way. As part of this arrangement, we agreed to keep some of the details confidential until intellectual-property issues are finalized. But we’ll share as much as we can as quickly as we can. In the coming weeks and months we’ll publish additional articles on our website, in the magazine, and on “The Runner’s World Show” podcast, reporting on the progress the athletes and scientists are making toward the sub-two-hour goal.]

For the three athletes involved, agreeing to forgo the lucrative spring marathon season is a calculated risk—but one with a possibly historic payoff. “I know one day [two hours] will be broken,” Tadese told us through an interpreter. “I want to be part of it.” Though the company hasn’t disclosed how much the project will cost, or what financial incentives the athletes will have, it’s a safe bet the sums involved are substantial.

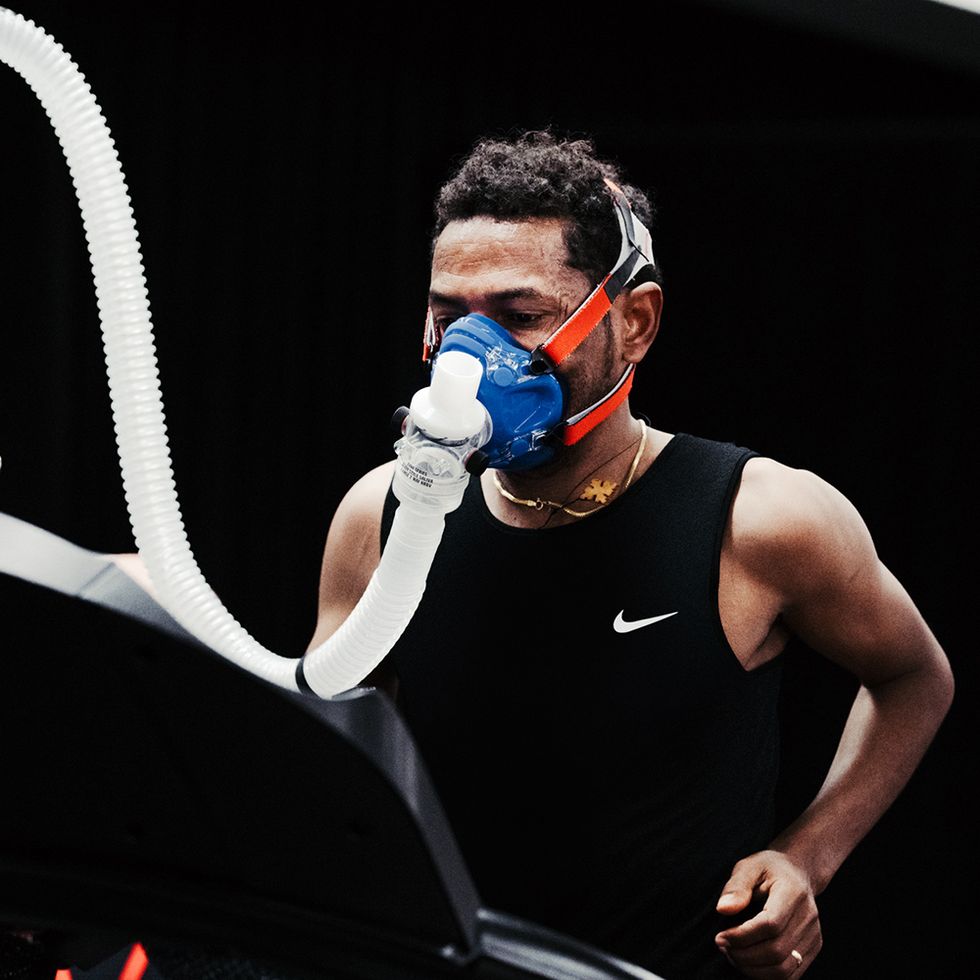

RELATED: Listen to a preview of this week’s “Runner’s World Show,” in which Willey narrates Tadese undergoing a treadmill test at Nike headquarters.

Nike’s announcement will undoubtedly raise eyebrows. Just two years ago, in a data-driven investigation of nike huarache in guangzhou india china america, I concluded that the barrier would be broken in 2075. That admittedly pessimistic prediction was based on the assumption that the record would continue to be shaved down by small margins, in keeping with previous trends.

But Nike is instead looking to carve a full three minutes, or about 2.5 percent, off the record—an unusual, though not entirely unprecedented, leap. Paula Radcliffe lowered the women’s marathon record twice for a total improvement of almost exactly 2.5 percent over the previous record; her record of 2:15:25, set in 2003, still stands.

Still, reverse-engineering such a big breakthrough requires a different approach from the incremental gains that Nike researchers have been pursuing for the last 40 years. “We know that we need to break the two-hour marathon. That’s a defined outcome,” says Brad Wilkins, the director of NXT Generation Research in the Nike Sport Research Lab. “So now let’s take a step back. What do we need to understand scientifically? What are the problems that we need to solve?”

Nike isn’t alone in believing that the barrier is nearly ready to fall. In late 2014, Yannis Pitsiladis, a professor of sports and exercise science at the University of Brighton in Britain, launched his Sub2Hr Project with an initial goal of breaking the barrier within five years. While Pitsiladis’s initiative has struggled to raise the $30 million he estimates will be needed, he is already working with Ethiopia’s Kenenisa Bekele, who ran 2:03:03 in Berlin in September to become the second-fastest marathoner in history.

Pitsiladis’s goal spurred some heated criticism. South African sports scientist Ross Tucker, for example, nike air max silver 2008 chevy tahoe within the current rules of the sport. “[W]hen sports science promises and then under-delivers,” he wrote, “it actually hurts us in the long run.”

Nike is keeping much of the Breaking2 plan under wraps for now, and many of the details are still being finalized. It is unlikely the quest will take place during a traditional, open marathon; rather, it will be held on a closed course, at a time and place believed optimal by Nike. It’s unclear whether the record, if achieved, will be sanctioned by the rule-bodies such as the IAAF or the Association of Road Racing Statisticians.

“The sub-two-hour marathon is one of those epic barriers that people bust through,” Nike’s VP of Footwear Innovation, Tony Bignell, told us. “It’s like breaking 10 seconds for the 100 meters or 4 minutes for the mile. At the end of the day, we just want to show it can be done. We want to show that it’s within the capability of human physiology.”

The company also has not yet announced a plan for drug testing the athletes, but has acknowledged the need to be transparent about its monitoring program.

Five keys

So why does Nike think it can do in a matter of months what many thought was impossible for years, or even decades? For one thing, the company’s size and resources allow it to chase every possible time-saver. In our meeting with the Breaking2 team, they emphasized five key areas that will need to be optimized or improved:

1. Athlete selection: No matter how perfectly everything else is planned, there are probably only a few people on earth who have a chance of breaking two hours.

The team started with a pool of the hundreds of distance runners that Nike sponsors—a large group, but one that notably omits the three most recent marathon record-setters, Kimetto, Wilson Kipsang, and Patrick Makau, who are all sponsored by Adidas. Nike further narrowed the field by looking for sub-2:05 marathoners and sub-60-minute half-marathoners, and then examining their recent performance profiles. Over the past few years, 18 of the most promising candidates visited Nike HQ for a few days of physiological testing. One of the elements: a two-mile run at sub-two-hour marathon pace—4:34 per mile—to see how the athletes looked, followed immediately by an all-out 400-meter lap.

It wasn’t just numbers and PRs. The team also spent lots of time with each athlete, considering who had the most room to improve and searching for the intangibles in attitude and outlook that might make the difference between success and failure. The three athletes who were finally selected are quite different from one other; we take a closer look at each of them below.

2. Course and environment: It’s no secret that the details of the race will make a big difference. Temperature, hills, turns, drafting, and pacing all play a role, and each can be optimized beyond what’s typically seen in big-city marathons. As our sub-two-hour feature noted, just getting the drafting right could shave 100 seconds off an elite marathon time, according to wind-tunnel estimates.

Exactly how Nike will choose to organize the race remains to be seen, but the company has the resources to create circumstances that are as conducive as possible to success.

3. Training and 4. Nutrition/hydration: These are the basic areas that most of us worry about when preparing for a marathon. Nike has a huge scientific staff ready to offer every possible support in these areas; still, over the coming months, each of the three athletes will continue to train with his own coach and in his own environment. Getting this balance right, so that the athletes benefit from extra support without disrupting what has worked so well for them in the past, will be a delicate task.

5. Equipment: Shoes and apparel, of course, are Nike’s bread and butter. Plans in this area remain very much in progress, and aren’t yet public.

The athletes

In the end, of course, none of the science matters without athletes capable of executing the plan. Here, in no particular order, is a primer on the contenders:

Eliud Kipchoge

Country: Kenya

Age: 32

Height: 5’6”

Weight: 115 pounds

Best times: 12:46 (5000 meters), 26:49 (10,000 meters), 59:25 (half marathon), 2:03:05 (marathon)

Quite simply, Kipchoge is the best marathoner in the world right now—the Olympic gold medalist from Rio, 13 years after he burst onto the scene with a surprise World Championship win in the 5,000m as an 18-year-old. He has shown unprecedented consistency in the marathon—with seven victories in his eight career marathons—but remains humble, jual nike sb dunk low nike huarache 2015 white and pink black women blue.

Three weeks ago, Kipchoge won a half marathon in Delhi in 59:44—an impressive time, to be sure. But can he go twice the distance at nearly the same pace? He smiled when we asked him. He’s not in peak condition right now, he explained—but still, he admitted, “it’s really intimidating, mentally.” If there’s one question about Kipchoge, it’s this: Can someone who’s so clearly at the top of his game, and who has been at the top for over a decade, find room to get even better?

Lelisa Desisa

Country: Ethiopia

Age: 26

Height: 5’9”

Weight: 125 pounds

Best times: 27:11 (10,000 meters), 59:30 (half marathon), 2:04:45 (marathon)

When Desisa was a kid, his school was a 50- to 60-minute walk away from his rural home—not far enough for the aspiring runner, so he would give his books to his friends and run a longer way home. These days, he is best known in the United States as the man who won the Boston Marathon in 2013, only to see his triumph turn to tragedy when bombs exploded two hours after he crossed the finish line. He later returned his first-place medal to the city of Boston in a public ceremony, and in 2015 he won again under happier circumstances.

Among the three runners, Desisa is the young gun and potentially the most untapped. His marathon best of 2:04:45 was set in his very first marathon, at just 23, and he feels that with the Nike support team he can improve dramatically. “We see each other as brothers, as friends,” he says of his new teammates. “But when it comes to running, we’re competitors.” In other words, he wants to be the one to break the barrier—and he believes he can: “Yes, God willing, I’ll do it.”

Zersenay Tadese

Country: Eritrea

Age: 34

Height: 5’3”

Weight: 119 pounds

Best times: 12:59 (5,000 meters), 26:37 (10,000 meters), 58:23 (half marathon), 2:10:41 (marathon)

Tadese is both the most obvious and most surprising pick of the three. Let’s start with the pros: He’s the world record holder at the half marathon, and four-time world champion at that distance. He’s also an Olympic medalist on the track and a World Cross Country champion. More intriguingly, physiological testing panther air max nike backpack sale women amazon British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2007 pegged Tadese as having “one of the lowest (if not the lowest) ever published values” for running economy, a measure of efficiency analogous to fuel economy in a car. Lower is better in running economy, meaning Tadese is one of the most fuel-efficient runners ever seen—a very useful trait for a marathoner.

The puzzle, then, is why Tadese’s attempts at the marathon thus far have been so disappointing. His best of 2:10:41 is far from his presumed potential. Moreover, most of his best performances came prior to 2012; his eighth-place finish in the 10,000 meters in Rio marked a return from relative obscurity, but was still far from his best. Based on their assessments, the Nike team clearly believes that Tadese has what it takes—and that they can help him finally unlock his considerable marathon potential.

My take

I’ll be honest: When I first heard about the project and timeline, I laughed. And having had a peek behind the scenes, the goal still seems wildly audacious.

Still, I left Oregon feeling it’s possible. I don’t think I’d go so far as to call it probable. In the marathon, after all, the smart betting advice is to always take the over, simply because the event is so arduous and unpredictable. Nike will be doing its best to control every variable that is controllable, but the race is still 26.2 miles long. That said, if all goes well over the next five or so months, I expect to see the first serious attempt at a sub-two—and if it succeeds, I won’t be totally shocked.

* * *

Alex Hutchinson is a contributing editor at Runner’s World who writes The Fast Lane and Sweat Science columns.