Scott Viands wanted to stay by his 8-year-old son’s side. He’d signed up for the NCR Marathon in Baltimore to accompany Nate during his first marathon.

But they went out much faster than anticipated. Too fast. The sub-eight-minute clip took its toll quickly and Viands found himself in trouble soon after they started.

Nate, however, looked strong. His stride fluid, his mind in the zone. He knew his dad, a seasoned ultra runner, was struggling to chase after him, but he couldn’t help but want to move, farther, faster than either of them anticipated.

Viands watched his son’s heels motoring forward with the “why did I sign up for this” blues ringing in his head.

Nate’s mom, Danielle, would not be happy if the two separated, but that was essentially what was happening by mile eight. Nate would run ahead of his dad, meet his mom at the aid station to refuel, and when dad caught up, keep going. The gap increased with every aid station.

Eventually, Viands made a decision. With his father’s blessing, Nate left his dad in the dust.

“He just took off,” Viands says. “Every once in a while at an aid station, I’d ask, ‘Did you see a little guy come through?’” and they’d be like, ‘yeah, he’s 10 minutes ahead of you.’”

Even though dad was out of sight, his mother still stopped him at every aid station to fuel. She knows he didn’t want to stop long, but she worried.

“I was slowing him down at aid stations, telling him to pace himself and wait for my husband,” Danielle says. “Honestly, he probably could have gone even faster.”

Nate’s parents never wanted to slow him down, not in any part of his life. This was a decision they made three-and-half years earlier at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. At the time, Nate wasn’t old enough to understand what was going on. His parents had a difficult time understanding themselves. All they knew was they would make sure Nate lived life as a normal kid.

Health & Injuries. Nate, a month shy of turning four, was left in his grandmother’s care. Scott remembers his mother’s voice shaking when she got them on the line. “Something’s wrong,” she said. “Nate’s not well.”

Nate had symptoms prior to the vacation, but they had shown up gradually, so the family thought little of it. But grandma hadn’t seen Nate in a while, so when she saw Nate’s symptoms of dark circles under his eyes, paleness, bruising, fatigue, nosebleeds and low-grade fevers, it was a dramatic change. They returned home, went to the emergency room, and relayed the gradual progression of his apparent illnesses.

Viands thinks Nate’s doctor had suspicions of Nate’s prognosis from the beginning. Tests were ordered directly, and the results came back the same day. With those in the medical experts’ hands, the doctors advised the Viands to head to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia as soon as possible.

Watch: Nate, Parents Talk About Nate’s Running Success

There, more tests, more blood work. Oncologists studied the results until Viands and Danielle were brought into a room with a box of tissues on the table.

There were a lot of words the family didn’t know thrown around, but the only one that mattered was leukemia.

“From there, we began our journey with the cancer diagnosis of a 4-year-old,” Viands says. “It’s not really something you’re expecting to ever, ever hear or deal with, you know? It changed our lives forever.”

The Viands sat in that room for a bit not knowing what to do. They knew what they had to tell Nate, but how?

They attempted to have a serious discussion right then at the hospital, with him in the waiting area of the hospital. But Nate, sitting on the tile in a youthful state of bliss, focused on nothing other than the wheels of his toy truck, couldn’t understand. He wanted to paint the tires. The word “cancer” fell out of his parents’ mouths and buzzed in the air. But to him, it was just a word without meaning; it was beyond the mental reach of a 3-going-on-4-year-old.

Scott and Danielle knew things would not be the same, but they decided it was best to keep it as close to the same as possible. They would certainly look at their son in a slightly different light, but when it came to how they lived, they kept it business as usual.

“I never wanted him to think he was sick,” Viands says. “A lot of these kids that get ill really get treated like they’re ill. I didn’t want him to think he was different.”

That was tough at first. For the first nine months after his diagnosis, Nate was pushed to the brink with each intensive chemotherapy session. His energy dipped low enough to make walking up the stairs nearly impossible. Worse, with an already weakened immune system, Nate was confined to his house.

But after those long, lonely nine months, the cancer weakened. The heavy chemo would stop, but he’d still need milder and less frequent sessions along with daily medicines including pulses of steroids. He was still in the maintenance phase and would still need to undergo spinal taps, and Lumbar punctures. But with less chemo, Nate regained strength. After being cooped up so long, Nate’s parents, both runners and outdoor enthusiasts, knew what to do: get him out of the house.

“You’re not promised tomorrow,” Viands says. “As soon as he came out of heavy chemo and we started doing stuff, it was like there’s going to be no regrets. We’re going to say yes to everything.”

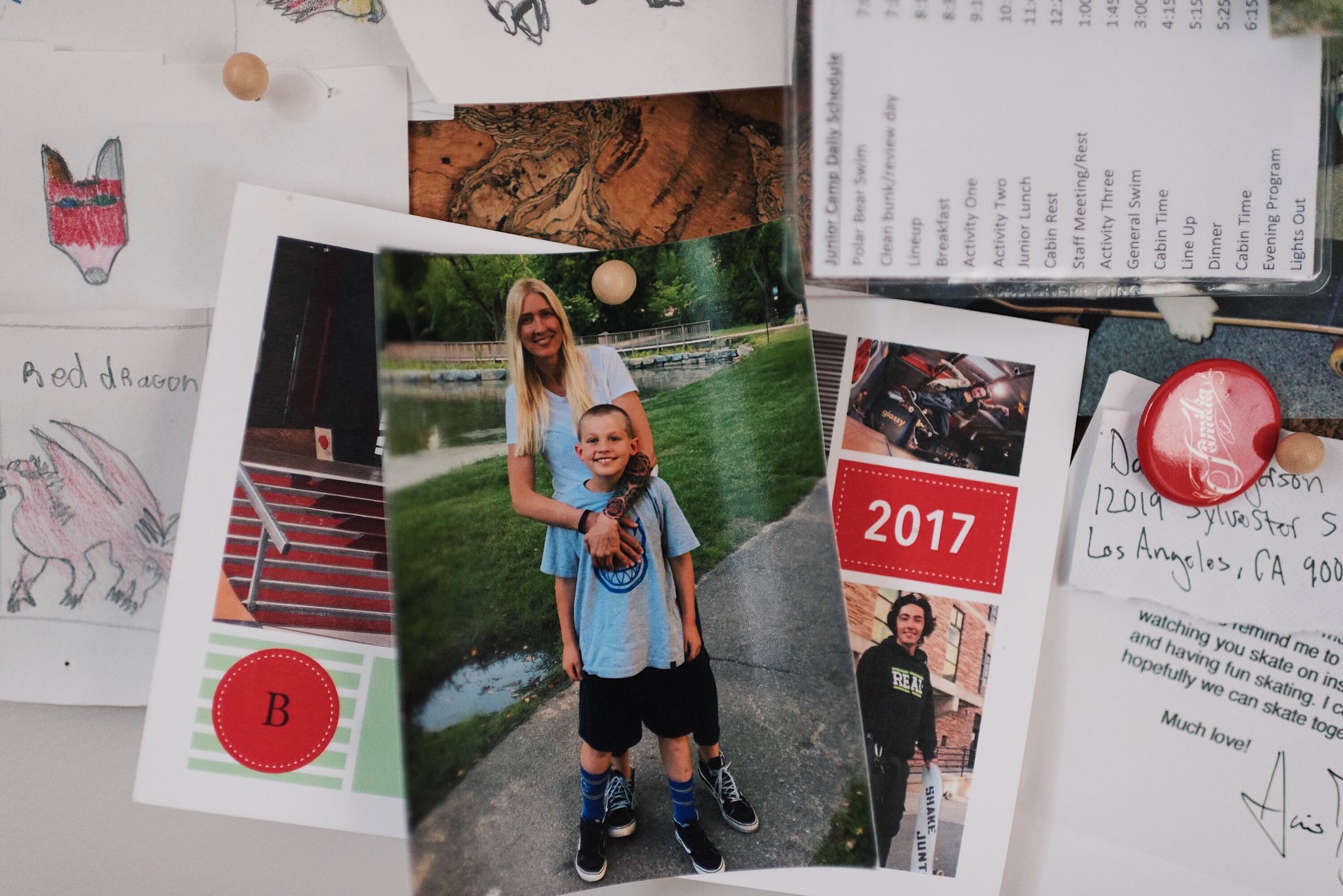

Running wasn’t the first thing Nate did. It was actually skateboarding. He had an intensity for it that kept him attempting to learn tricks even as the sun went down and the police closed the park for the night. The determination to set a goal, work for it, and achieve it came naturally to the 6-year-old.

Next, he tried cycling. His parents got him a 16-inch-wheel REI bike, so he could accompany his father while he ran. At first, Nate needed some assistance; Scott pushed him at times. As Nate’s endurance built up, he was able to conquer 10 miles with no problem.

The bike was the norm for a while until one spring day in 2015 when the father-son duo arrived at Pennypack Trust, a running spot near their home. They got out of the car, opened the trunk, and Nate’s bike wasn’t there. It was at home. Neither remembered to load it.

Only a few miles from home, they could have easily retrieved it. Instead, Nate had another idea: “I’ll just run with you.”

Nate had never run a single mile before. But Viands thought that it wouldn’t hurt to let him try. Despite all of the treatments and medicines, his son had already excelled in skateboarding and cycling. Besides, if Nate got tired, they would simply cut the run short. They didn’t have to.

“I’m like, ‘alright, let’s go,’ and he ran like two or three miles with me, no problem, over rolling hills,” Viands says. “I didn’t know how far to push it at the time, I was like that’s cool, and from there, the bike became less and less and the running became more and more.”

Nate glided along with a natural gait. It propelled him over those first miles with ease.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back. Just like the bike, each run made him stronger and allowed him to go longer. He ran his first half marathon when he was five, four months after that first run. He then bested that time to around two hours when he was six.

Half marathons were the longest races he did for a while, but not the longest runs. His parents would take him into the mountains all over the East Coast for miles, and still he would conquer the obstacles, all while dealing with cancer treatments. He ran all the way until September 2017, when he walked out of his final chemotherapy session, and then he ran even more.

This past Memorial Day weekend, Viands and Nate did a 27.9-mile trek through trails on Catoctin Mountain in western Maryland. With 17 miles completed the first day and about 11 the second, Nate realized he could go longer. He wanted to go longer. That sparked an interest in him to do a marathon that fall. Dad picked.

“I chose the race because it was a soft surface for me,” Viands says with a laugh. “I signed him up and figured if no one said anything, they weren’t going to stop us from running on race day. I kept waiting to get an e-mail at some point, or someone to ask a question and then no one said anything.”

But his parents didn’t want to be the only ones running with him. They wanted him to experience running with a team—with other kids.

Research led them to the Ambler Olympic Club. But they found them in mid-October when the season was essentially over. Only a regional meet remained.

But the coach took him in, and put him in the CCCNYC East Regional Championship lineup. Nate toed the line two weeks later and won the race outright. Not only that, he crushed his competition. “Halfway through, I was 20 seconds ahead,” Nate says. His victory earned a trip to nationals three weeks later.

“Initially, we were like, ‘there’s no way we’re going to Kentucky for this race,” Danielle says. “Then his coach said he could be competitive there. We eventually caved.”

At the CCCNYC National Championships, the competition was a little deeper. There were 208 other kids from 30 states all battling it out. Nate beat them all with a time of 7:31. “When I was at the start, I was kind of like nervous and then halfway through the race, I was ten seconds ahead,” Nate says. “It was fun.”

The following weekend was the race he’d been training for: the marathon, which he finished in 3:32 on the dot, good enough for 55th overall.

Nate was sore the next morning, but he was back to his crazy energy levels by the afternoon. His parents were stunned in the best way.

“Given his backstory and everything that had gone on, I don’t want to say that he deserved it,” Viands says. “A lot of people deserve a lot of things, a lot of people get dealt tough hands, have rough situations, but like to see him work hard at something and go through what he went through, it was special moment to watch as a parent.”

Less than two weeks post-marathon, Nate is still running strong. He has a lot of energy on a Thursday afternoon when he arrives at Pennypack Trust, the place where ran his first miles when the bike was left at home. As he runs up and down the grassy trails, his mind is focused on something else, like the boy preoccupied with painting the wheels on a train three years ago.

“Can I go in the woods?” Nate asks his parents, who, as you would expect, let him go off on the familiar trails.

Nate isn’t that 3-year-old anymore. He has questions for his parents now, the ones they have been waiting him to ask when he was ready. Over the last six months, those questions have become more common to the point where Nate seems to realize for the first time that he could have died.

He’s still not entirely done with leukemia. Things look very promising considering he hasn’t had chemotherapy in over a year, yet he won’t be fully cleared until June 2019—five years post-diagnosis. Only then will the family sleep easier.

Nate, his mom says, is a wonder. He has a calm demeanor about everything in life. He has a determination to accomplish anything, a primal instinct to keep going, and the will to overcome tough odds. His parents see zero quit in him. Whether that’s battling cancer or beating the wall during a marathon, he’ll always keep going.

Why Can’t I Eat After a Marathon Runner’s World and Bicycling, and he specializes in writing and editing human interest pieces while also covering health, wellness, gear, and fitness for the brand. His work has previously been published in Men’s Health.