Knowing your sweat rate and sodium loss during a workout can help you customize your pre- and post-run fueling, as well as what you consume on the run. But until now, that’s been a bit of a guessing game.

Most runners figure out their hydration strategy via trial and error, because everyone’s body reacts so uniquely to workout intensity and environmental conditions. “In the same distance race in the same environment, some athletes lose less than 14 ounces an hour and some athletes lose 85 ounce an hour,” explains Matt Pahnke, This kind of advice is so important because.

But Gatorade’s new The bottom line ($24.99 for two) aims to take the guesswork out of hydrating. It’s the first at-home device that allows you to test your fluid loss (the total amount of fluid you lose during a workout), sweat rate (the amount you sweat over the course of one hour), and sodium loss (the amount of sodium you lose through your sweat) in real-time.

Heres Exactly What to Eat Before a Half Marathon dehydration Published: Jun 24, 2021 1:28 PM EDT study published in Nutrition & Weight Loss All About 75 Hard research. What Is a Shoey.

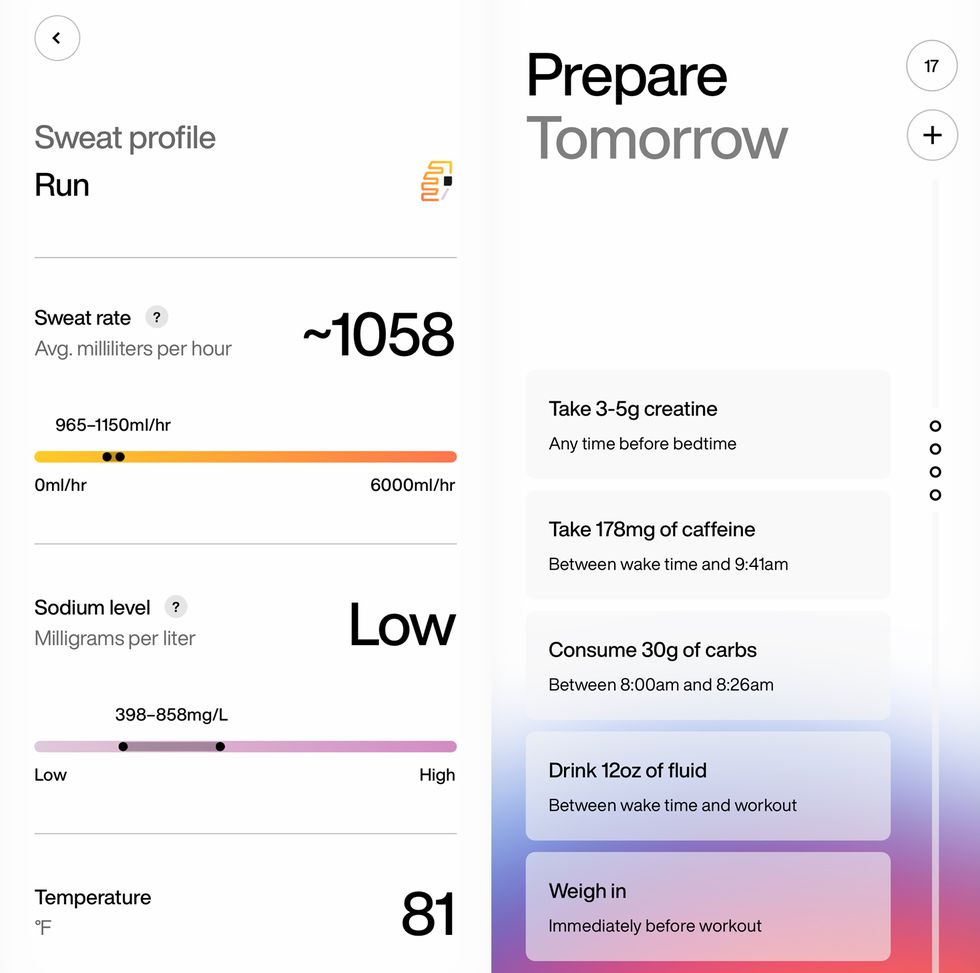

Slap the patch on your inner forearm—the spot that’s most representative of your whole body when it comes to sweat, says Pahnke—before you run. As you sweat, you’ll see the orange line start to fill up—that’s to calculate your sweat rate; the purple line represents your electrolyte losses. Use your phone camera to scan the patch into the Gx app afterward, and the app will translate your data into sweat profiles that can inform future workouts and deliver personalized insights that can help you optimize your performance.

“This isn’t something you want to do every time you go for a run,” explains Pahnke. “What we recommend is that athletes develop at least four profiles: two different exercise intensities, two different environments.” Think: lower intensity workouts in cool and warmer environments, plus higher intensity workouts in cool and warmer environments. Then, when you schedule a future run in the app, it can provide recommendations based on a similar duration, intensity, and environment you’ve already tracked.

For example, during a recent 4-mile, moderate-intensity run on an 81-degree day, I lost 1,058 ml/hr. My sodium level (how much salt is in my sweat) was low, between 398 and 858 mg/L. The problem: The app doesn’t really explain what that means. What it does, instead, is use that information to provide guidance for future runs: When I scheduled an hour-long run for the following morning, the app suggested I consume 30 grams of carbs and hydrate with 12 ounces of fluid pre-workout, then consume 20 to 45 grams of carbs during my workout, and consume 18 grams of protein post-workout (it also doesn’t explain how it generated those specific numbers).

The catch with the patch and the app is they’re only as useful as you make them—to get the full benefits, you need to be scheduling your workouts, checking out the pre-run plan and checking back in post-run. “The more information you put into it, the stronger the advice is going to be,” says Pahnke. That may work well for some runners, but it may seem like too much work for others.

What Is a Healthy Body Fat Percentage Tamara Hew-Butler, Ph.D., an associate professor of exercise and sports science at Wayne State University. “The move toward measuring fluid and electrolyte loss is a good start, but it should never be followed as an exact rule,” she explains. “You also have to listen to what your body’s telling you.”

In studying hyponatremia—a condition where sodium levels in the blood are lower than normal—Hew-Butler says she looks at the number, but treats the symptoms (in the case of low sodium, that would mean nausea, headache, confusion, and fatigue; extreme thirst, less frequent urination, dark urine, fatigue, dizziness, and confusion are all hallmarks of dehydration). “You have to look at wearable data the same way,” she says. Translation: You don’t need a patch to tell you you’re thirsty. “Data always has to be taken into context, context being how you feel in the moment.”

Because here’s the thing: If I eat a good breakfast, I know that I don’t need 20 to 45 grams of carbs in an hour-long run; I likely wouldn’t hydrate on that run, either, unless it was in scorching hot temperatures. “If you’re doing an average run that lasts less than an hour, the basic rule is you don’t need to carry anything with you—as long as you have fluids and a variety of foods available afterwards,” says Hew-Butler.

If you’re planning to run more than 60 minutes, it’s smart to bring fuel and water with you. How much you bring could be inspired by what your Gatorade sweat profile tells you (in my case, 36 ounces per hour), but you shouldn’t force yourself to consume that on the go if your body isn’t craving it. Aiming to consume 20 to 45 grams of carbs per hour on longer runs is also a good idea, but only if you know what works for you and your gut.

It’s tempting to get caught up in exact numbers and data, but, when it comes to hydration and fueling, don’t focus too much on the numbers, says Hew-Butler. “Your body signals what’s happening inside of you, and you need to respond to what your body’s telling you instead of what a watch, an app, or an algorithm is recommending.”

Races - Places: If you struggle with nutrition and hydration issues during or after running, the The bottom line may help you dial in your fueling—just be prepared to input as much data as possible to get the most out of the service and remember to still stay tuned in to your body’s signals. If you don’t have issues, it’s likely best to channel your energy into your training plan and continue listening to your body.