Editor's Note: This article was adapted from First Ladies of Running: 22 Inspiring Profiles of the Rebels, Rule Breakers, and Visionaries Who Changed the Sport Forever, by Amby Burfoot.

No marathoner has ever been less well prepared than Roberta Gibb—not even Pheidippides, is my guess. After rising early on April 19, 1966, Gibb, then 23, had no clue what to eat, how to dress, or how she would get from her parents’ home in Winchester, Massachusetts, to the Boston Marathon starting line in Hopkinton.

After eating “something light” (she can’t remember what), she scrounged through the laundry room to find a navy-blue hooded sweatshirt and a pair of her brother’s Bermuda shorts. She pulled these over her normal running gear—a black one-piece bathing suit. The shorts drifted south, so she cinched them around her waist with a length of—no kidding—twine.

When her father stormed from the house declaring her “delusional,” Gibb had to cajole her only slightly less dubious mother into a ride to Hopkinton. It was about 90 minutes before the noontime start when she was dropped off on the outskirts of town. Gibb, then living in San Diego, had never been to Hopkinton, had never run a track meet or road race, and had no idea what to expect.

She recognized only this: Her planned activity was verboten, perhaps even illegal. She had to avoid detection. As she ran up Route 135 toward the Hopkinton Town Common, she kept tugging the hoodie high over her blonde ponytail and glancing around furtively. She could have been mistaken for a petty thief scoping out the neighborhood.

At the Town Common, Gibb smelled coffee, popcorn, and fried dough. Vendors peddled balloons and other trinkets to hundreds of kids giddy over their day off from school. “It was a pure celebration of spring, and I wanted to enjoy it,” Gibb recalls. “But I was too concerned. Every time I saw a policeman, I would slink away. I thought they might arrest me and throw me in jail.”

The west side of the Town Common was bordered by Hayden Rowe Street, site of the starting line in 1966. There she spotted a stream of runners jogging toward her. They were coming from Hopkinton High School, a half-mile distant, where they had received cursory physicals and picked up their race numbers. Now they were all lining up. Danger! Danger! Boston Red Sox Manager Completes Half Marathon.

Gibb retreated and found a spot behind several roadside forsythia bushes 150 yards in front of the starting line—the perfect place to crouch and hide. She waited…and waited. There was too much time for thinking. Could she avoid confrontation? Could she go the distance? “I wondered, Why am I doing this? Does it really matter?” she says. “No one but my mother knew I was in Hopkinton, so there was no price to pay if I changed my mind.”

Two months earlier, she had written from her home in San Diego to the Why am I doing this? Does it really matter to request a marathon application. Race director Will Cloney sent her a terse reply, essentially: No, she could not enter. The Boston Marathon is sanctioned by the Amateur Athletics Union, and AAU regulations prohibit women from racing more than 1.5 miles. Besides, the reply went, women are not physiologically capable of covering 26.2 miles on foot.

“At first I just laughed, it was just so ridiculous,” Gibb says. “I was running two or three hours a day, and it made me feel so wonderful. I thought, If only everyone else could feel as good as I feel when I’m running, it would probably solve most of the world’s problems. Then I got angry. It was a classic catch-22. How could women prove that we could accomplish something if we were never given a chance to try? That’s when I realized that if I ran the marathon, I could explode one of the false beliefs about women’s limitations.”

Four days before the marathon, Gibb rode her motor scooter to downtown San Diego, where she bought her very first pair of running shoes, men’s size 6 Adidas—a considerable change from the soft-soled nurse’s shoes that she usually ran in—and boarded a Boston-bound bus. She arrived Monday evening, April 18, at 6 p.m., then grabbed a taxi to her parents’ home in Winchester, nine miles north. (The Boston Marathon did not move to its now-familiar Monday race day until 1969.) Famished, she wolfed down the roast beef dinner her mother put in front of her.

At precisely noon the next day, Gibb heard the starter’s gun, sensed the excited buzz of nearby spectators, and picked out the staccato slap-slap of hard, thin-soled shoes. When about half the runners had passed, she emerged from the forsythia, walked to the road’s edge, and broke into a relaxed run. Freedom.

Gibb had, so far, escaped the authorities. But she now faced a bigger threat—the roughly 500 runners around her. Men alone had ruled the Boston Marathon since 1897. They would eventually discover her ruse and probably wouldn’t be pleased; she kept picturing a phalanx of guys bulldozing her off the road.

For the first mile, everyone seemed excited to be under way, and she heard happy chatter on all sides. Then an eerie quiet fell. Without looking around, Gibb was certain she was being checked out. Now what?

On a dazzling afternoon last October, Roberta Gibb leads me on a long, rambling tour of Rockport, Massachusetts, her “root home,” as she calls it. It’s a small fishing village turned arts and tourist hangout 32 miles northeast of Boston.

Gibb, the oldest of two whose father was a professor and mother a frustrated homemaker (herself a Swarthmore College grad), spent her childhood summers in the New England town. Its beaches and ever-changing waters have cast a spell of sorts on her; they are never far from her thoughts and actions. She bought her own narrow, ramshackle home here three decades ago.

She takes me first to scruffy Old Garden Beach, so covered by seaweed and boulders that it’s hard to find any sand. This doesn’t bother Gibb, who eases down a stone stairway and walks through the sea foam. She’s wearing jeans, a plum-colored sweater, and an olive cap that does little to tame her thick, frizzy hair. She’s 73, but looks 20 years younger. In appearance and speech, Gibb is like a primal incarnation of some mythological creature.

“I remember listening to the waves while my grandmother told me bedtime stories about local sea monsters,” she says. “My father would take me to the beach and challenge me to figure out where the ripples in the sand came from. I felt transported by the beauty of everything I saw, and I’m still trying to piece together the miraculous patterns of life.”

In high school in Winchester, Gibb found herself out of sync with girl talk and social pressures. “I wasn’t interested in clothes or the latest hairstyles or who was going to the prom with whom,” she says. She preferred tramping through the woods with five neighborhood dogs.

In the early 1960s, she attended Tufts University and took night classes at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, drawn to sculpture and its required knowledge of human anatomy. After that, she graduated from the University of California, La Jolla. She then interviewed with famed Massachusetts Institute of Technology neuroscientist Jerome Lettvin for a lab assistant job. She didn’t have extensive training in his field, and he didn’t appear to have much interest in her. Still, he asked: Have you ever done anything out of the box? Gibb couldn’t resist a grin before breaking into her Boston Marathon tale. She got the job. In the early 1970s, she went to law school and practiced law for 18 years. Today, she mostly makes art to sell on her website, bobbigibbart.net.

One spring day in 1964, at age 21, she overheard a family friend talking about the Boston Marathon. “What’s that?” she asked. The friend explained, but Gibb remained incredulous. “That’s impossible,” she declared. “How could anyone run 26 miles?”

Two weeks later she stood on the sidewalk, mid-marathon, and watched the runners file past. Gibb didn’t know where they had started, or where they were going. But she was mesmerized. “I felt that I had witnessed an ancient yet civilized tribe that was in touch with the most primitive human traits,” she says. “They looked so natural. That afternoon, something inside me decided that I was going to run the Boston Marathon. It was an edict from my soul.” She began her training the next day.

She had no plan, no book, no coach. She simply ran longer and longer distances around Winchester. “It was the first time in my life I did something completely for myself,” she says. “It wasn’t my teachers telling me to finish my homework, or my parents begging me to be more like the other kids. The running was only for me. That made it exhilarating and so much more meaningful.”

When her parents traveled to Europe that summer, Gibb packed up the family’s VW station wagon and headed west with her dog, Moot the malamute. Day after day, the New Englander encountered nature on a scale she had never known before, especially west of the Mississippi River: the Great Plains, the Black Hills, the Rockies. After driving all day, she and Moot set out on foot in the most alluring direction. They ran five miles, 10 miles, and sometimes more before turning back, and every night the pair slept under the stars.

Gibb planned to run Boston in April 1965, but sprained both ankles slipping on a curb a month beforehand. On Patriots’ Day, she watched again. More than the previous year, she longed to join in.

After her ankles healed, she trained even harder. That September, she rode a bus north to South Woodstock, Vermont, for, improbably enough, the Green Mountain Horse Association 100-Mile Ride. Horses and riders covered 40 miles the first day, 40 the second, and 20 the third. Gibb, who says she was the only runner, completed day one not far behind the horses. “How do you feel?” one of the riders asked her. “Really, really hungry,” she replied, having covered 40 miles without fuel.

She slept that night in a cold barn, and set off running again the next morning. She managed 25 miles before succumbing to a sharp knee pain. “The horse race probably wasn’t the smartest thing I’ve ever done,” she says, “but it showed me I had plenty of endurance.”

Four months later, she moved to San Diego to marry Navy officer Will Bingay, whom she had met in college several years earlier (the marriage didn’t last long). She continued her training there, mostly on the beaches and mountain trails. In February 1966, she mailed her request for a Boston Marathon application.

Less than a mile into the marathon, Gibb heard runners talking.

“Published: Apr 06, 2016 9:06 AM EDT?”

“What? No way. Girls can’t run the Boston Marathon.”

Unsure how to react, she glanced in their direction and smiled as prettily as she could.

“Health & Injuries!”

“Really? That’s so cool. I wish I could get my girlfriend to run with me.”

Several of the guys immediately clustered around Gibb: “What’s your name?” they asked. “Where are you from? Are you going the whole distance?” She nodded, returned the same questions, and the men shared their stories without hesitation. Everyone was friendly and receptive.

A mile later, Gibb felt herself over-heating in her sweatshirt. She told her running partners that she wanted to toss it, but was worried about losing her cover. “Don’t worry, it’s a public road,” they said. “No one can stop you from running on it, and we won’t let anyone hurt you.”

Sans sweatshirt, there was no hiding now. Reporters on the press bus spotted her, and sent reports up the road: There’s a woman running the marathon today! Radio stations shared the news, and thousands of listeners rushed to the course. Most expected a sideshow act; at the time, Bostonians viewed marathoners as oddballs. They had a saying: “It must be spring, the saps are running again.”

Yet from Hopkinton to Boston, to her amazement, Gibb didn’t encounter a single hostile moment. Some onlookers cheered: “Attaway, girlie, you can do it!” A policeman did lock his eyes on hers at an intersection. Gulp. “There’s a runner a block ahead of you,” he said. “See if you can catch him.”

Just before 12 miles, 38-year-old Navy commander Charles Stalzer blinked hard when a woman passed him. “She was running strong and I couldn’t catch up,” says Stalzer, now 88, who also ran the first 32 Marine Corps Marathons. “But I thought, No way a girl is going to beat me, so I stayed as close as I could.”

The news had a galvanizing effect on the women of Wellesley College. A smattering of them always turned out to cheer the runners. But no one wanted to miss the first woman, and multitudes rushed from their dorms. “I could hear them a half mile away,” Gibb says. “In those days, there was limited security, so the girls ran out into the road and raised their arms to form a tunnel that we ran through. I had to stoop down a bit to get through it. The sound was deafening.”

One of the excited students, Diana Chapman Walsh, would later serve as Wellesley president from 1993 to 2007. Of marathon day 1966, she has written: “The word spread to all of us lining the route that a woman was running the course. We scanned face after face in breathless anticipation until a ripple of recognition shot through the lines and we cheered as we never had before. We let out a roar that day, sensing that this woman had done more than just break the gender barrier in a famous race.”

Beyond Wellesley, Gibb noticed a woman holding a child. As she passed, the woman chanted, “Ave Maria. Ave Maria.” The scene struck a chord, and Gibb felt her eyes dampen. “It was as if she knew I wanted children,” she says. “And that I consider motherhood among a woman’s highest callings.”

Gibb held steady through the Newton Hills, encouraged by Alton Chamberlin, an upstate New York runner. He told her they were on seven-minute pace. And Stalzer continued to tail Gibb as close as he could. “I was surprised at how strongly she took the hills,” he says. “I had to work very hard to stay close. She was a wonderful-looking runner.”

Our stroll around Rockport meanders through a wooded preserve. I stoop to remove a turtle from the road; when I turn back to Gibb, she’s staring at a leaf in her hand. It’s mostly dead and brown, but with two spectacular veins of neon red and green. “I wonder what made this leaf produce these colors?” she asks. “Isn’t it amazing, the miracles around us, if only we take time to notice them?”

After several hours, Gibb and I return to her house. It has a small garden out front and a backyard that’s turning to meadow. We climb dark, curving stairs to her kitchen, and put on a pot of tea water. The last time I sat here with Gibb, three years previous, she had received another visitor, Tapping Gull, a large gray and white seagull. She says he’s been a regular for 17 years. Sure enough, he announced himself by tapping loudly on a kitchen windowpane, after which he and Gibb spent five minutes in intimate, cooing conversation.

The kitchen table hardly has room for our tea and toast among Gibb’s mini running sculptures. Barely a foot tall each, they’re lithe, limber, and elongated. I note that her work looks very different from most human sculpture. “Yes, classic sculpture is all about massive muscular forms and voluptuous women,” she says. “But when I sculpt runners, I want to show their leanness and particularly their vigor. They aren’t frozen in time. They’re moving.”

In the next room, Gibb drops to her knees to unfurl her latest painting. It’s a 4-by-18-foot acrylic-on-canvas swirl of sea monsters and underwater colors. At first, I can’t make out anything, but then I notice two large heads nuzzling each other. “These are the sea creatures my grandmother told me about long ago,” she explains. “I’m using them in a very abstract way to represent my dream that we can all live together in harmony.”

Gibb was sitting on her back porch during the summer of 1983 when the phone rang. The caller was Laurel James, director of the historic first U.S. Women’s Olympic Marathon Trials (Olympia, Washington, 1984). She wanted Gibb to sculpt the trophies for the top three women finishers. It was the first time since she ran Boston that Gibb had been recognized by the running world in any meaningful way.

The following May, Gibb flew to Olympia to watch the trials race and help award the trophies she had created. This was the marathon famously won by Joan Benoit just 17 days after knee surgery. “Joan has always been one of my heroes, the way she is so grounded in the culture and environment of Maine,” says Gibb. Benoit (now Samuelson) has frequently mentioned that Gibb’s sculpture is the only running award on display in her home; in 2008 she told Running Times, “There are only three in the world. It’s irreplaceable.”

At the top of Heartbreak Hill, Gibb overtook Rick Spavins, a 19-year-old distance-running acolyte from Long Island. “I recall the moment vividly,” he says. “I was running my first marathon, hitting the wall, and we were heading into a cold wind. Next thing I know, this woman goes by me. It was a bit of a blow to my male ego.”

Near the same spot, Gibb passed another 19-year-old novice, Paul Hoss, the New England freshman collegiate cross-country champion the previous fall. “When she went by me, I was absolutely shocked,” says Hoss. “A woman? In the Boston Marathon? But you could tell right away she wasn’t some joker going two blocks. She looked like a serious runner. Somehow, somewhere, she had prepared herself to cover the distance.”

The farther Gibb ran, the more she thought about the potential impact of her presence. Like other pioneer runners—including Julia Chase-Brand, who became the first woman to finish a road race at the 4.75-mile Manchester Road Race in 1961, and Merry Lepper, who became the first American woman to complete a road 26.2 in the Western Hemisphere Marathon in 1963—Gibb realized it was more important to look good than to finish fast. They were, after all, fighting to change attitudes within a male-dominated world with a narrow view of what it considered “appropriate.” She wasn’t pushing it, says Gibb. “I ran comfortably through the hills. I was only thinking about getting to the finish, and looking as strong and feminine as I could when I got there.”

Her dream run ended abruptly at mile 23. Gibb was accustomed to running on soft surfaces in her well-worn nurse’s shoes. Now the hard road, slipping socks, and new shoes caused severe blisters and her feet felt as if they were on fire. “I was barely moving,” she says. “I felt discouraged, disappointed. Like a failure.”

In Kenmore Square, past the 25-mile mark, Stalzer, the Navy commander, crept closer to Gibb. He had run previous Bostons and knew how the course zigzagged right then left in the final half mile. Gibb knew none of that. She stared down long, straight Commonwealth Avenue, dispirited. No banners, no crowds, nothing. Dammit. How much farther?

She asked a cop where the finish was, but he simply waved her forward.

At that moment, Stalzer saw her sag. “She must have been so depressed not to know where she was,” he says. “She slowed down noticeably. I knew this was my last chance, so I picked up the pace and passed her. If she had known the course, I doubt I could have beaten her. She was astonishingly fast.” Stalzer crossed the line in 3:21:00, 123rd place.

Gibb plodded onward. She wanted only to be done, to remove her shoes, to sip some water. The winners had come in an hour earlier, so she expected a quiet finish line. She made the final left turn, and saw it looming ahead.

Whoa, what’s this?

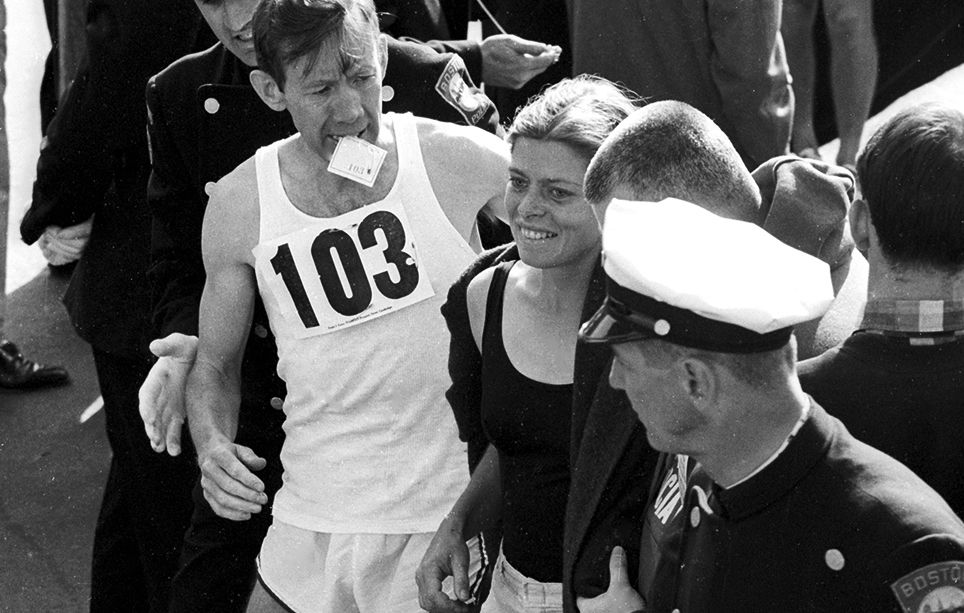

The area was buzzing with Bostonians there to see the first woman finisher, and every newspaper had posted its cameramen to get the money shot. In those photos, Gibb is relaxed and smiling when she crossed the line in 3:21:40, 124th place.

Massachusetts Governor John Volpe found her and offered his congratulations. Then she was led to a small room in the Prudential Center, where the press had at her. “They wanted to know why I ran and what I was trying to prove,” she says. “It seemed like they wanted me to say I was a man-hater. But that wasn’t right. I told them I simply loved running and enjoying the beauties of nature while I ran. Sure, I hoped to change some of society’s thinking about women, and what we could accomplish. But I didn’t care about beating men. I love men. I didn’t see any reason why men and women couldn’t run together.”

After that, Gibb followed the other finishers to a cafeteria, where runners were being served a postrace meal. Two security guards were positioned outside. Women aren’t allowed, they told her.

Gibb didn’t put up a fight. “I don’t like being the center of attention,” she says. “I didn’t care about eating the beef stew. Of course it bothered me that I could finish the marathon and still not be admitted to the meal; it was just another instance of doors closed for women.”

She grabbed a cab back to her parents’ home, hoping for some rest at last. No way. The place was mobbed. The newspapers had dispatched more photographers. This time they wanted domestic scenes—a woman doing womanly stuff. They asked Gibb to tidy up a bit and display her kitchen skills. Again, she complied without argument though the fiction made little sense. “I’ve never been much of a cook,” she says. “But I had one polka-dot dress, and I knew how to make fudge. So that’s what I did.”

The next day’s papers headlined her heroics. Boston’s Record American filled its front page with the banner: “Hub Bride First Gal to Run Marathon.” An editorial opined: “A girl in the marathon! Egad, is nothing sacred? Are there no careers and hobbies and sports reserved for gentlemen anymore? Still, if someone would guarantee that all future lady runners would be as pretty as she, we might be willing to OK them as regular entrants starting next Patriots’ Day.” Sports Illustrated began its coverage with the title and subtitle: “A Game Girl in a Man’s Game: Boston was unprepared for the shapely blonde housewife who came out of the bushes to crush male egos […]”

Meanwhile Will Cloney, the same BAA exec who had penned Gibb’s rejection letter two months earlier, issued a press release. It stated: “Mrs. Bingay did not run in yesterday’s marathon. There is no such thing as a marathon for a woman. She may have run in a road race, but she did not race in the marathon.” Finisher Alton Chamberlin rejected Cloney’s statement, noting that he had run most of the distance with Gibb. Yes, she ran the whole way, he confirmed. Not only that, he added, but “she didn’t look half as bad as some of the men.”

Gibb returned to Hopkinton the following year. Unlike Kathrine Switzer, who had registered under her initials and received a bib number for that year’s race, Gibb had no number. While Gibb started in the open with the men, and finished ahead of Switzer in 3:27:17, officials linked arms at the finish and wouldn’t let her cross. She won again the year after that (in 3:30), but again, was denied any real recognition.

After that, she stopped competing to focus on work, art, and motherhood (by then she had a son). She continued to run, and in 1982, at age 39, ran her PR, 3:19:48, in the First Lady of Boston.

Gibb and others like her are often labeled “trailblazers” and “pioneers.” And they were, of course. Yet it’s also interesting to note that they did not immediately set off a tidal wave of women’s running. They were simply too far ahead of the curve. Title IX was still six years distant (enacted in 1972), and it would be seven years before the infamous Billie Jean King-Bobby Riggs tennis match brought worldwide attention to women’s struggle for recognition in sports. The pioneer runners of the 1960s broke down barriers, but they didn’t attract many followers. When the Boston Marathon finally allowed women runners to enter officially in 1972, there were only eight of them among a field of more than 1,000 runners. It wasn’t until Oprah Winfrey finished the Marine Corps Marathon in 1994 that road-race and marathon participation exploded among women. Female entries soared in Boston in the 1990s and 2000s, and continue to rise today.

Gibb never sought recognition for what she did. Instead, she has embodied a lifestyle that will sound familiar to runners. She runs for the joy, challenge, personal exploration, and quiet fulfillment of it. She runs to commune with nature and connect with her own animalism. She runs because something stirs her, and that is enough.

In 1996, on the event’s centennial, Gibb was finally recognized for her three consecutive Boston wins. The BAA awarded both her and Sara Mae Berman—also a three-time winner, in 1969, ‘70, and ‘71—their long-overdue winner’s medals. “Next to the day my son was born, it was the happiest day of my life,” Gibb says. “I didn’t feel any anger or resentment at all [toward the BAA], just pure joy.”

With this year’s Boston marking the 50th anniversary of her historic run, she may attempt another go at 26.2. She started training last summer; by December, she’d completed a four-hour run. At press time, she figured she’d make her final decision sometime in March. “I’ve got nothing to prove,” she says.

Gibb never sought recognition for what she did. She runs because something stirs her, and that is enough.

“I did my part 50 years ago: I finished the marathon and changed some beliefs about women. I’m thankful for all that eventually happened in our sport. Most of all, I’m proud and happy that so many women are running today, and continuing to show what we’re capable of.”

Adapted from First Ladies of Running: 22 Inspiring Profiles of the Rebels, Rule Breakers, and Visionaries Who Changed the Sport Forever, by Amby Burfoot