Vanessa Fraser stood alone on the start line at San Francisco State’s Cox Stadium. Wearing her red-and-black Bowerman Track Club colors and her long, blond hair in a low ponytail, she gazed out at the eucalyptus grove flanking the first turn of the outdoor track. On her bib was the number 701.

Several racers milled about nearby—but they weren’t her usual elite competitors. One had white hair and wore a vintage red-and-blue tracksuit. Another had braces on her teeth and was there with her mother. Small children toddled beside some of the other women.

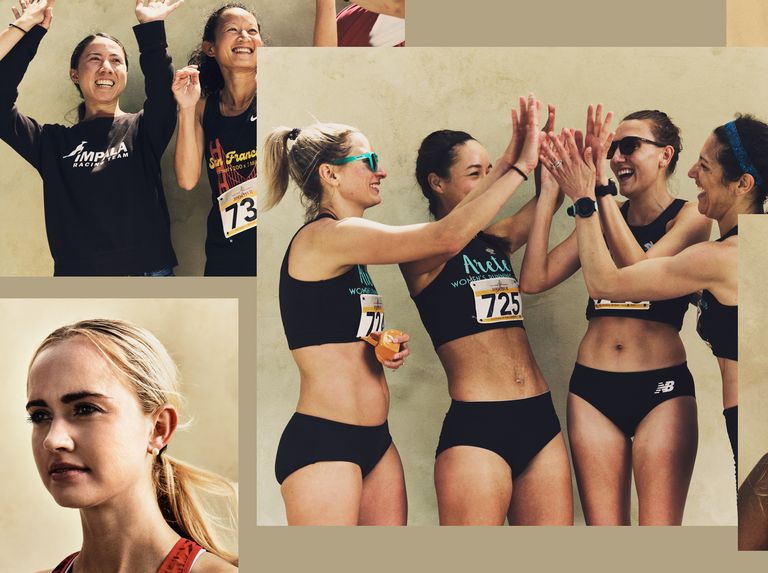

Usually dormant on early Sunday mornings, the stadium buzzed with energy for San Francisco’s fourth attempt at a world record in the women’s 100x1 mile relay—an event in which 100 competitors each run a mile in an effort to set the fastest total time.

Fraser told me that when she learned of the world record attempt, she was drawn to the idea of a collective mission, a rare thing in the world of professional running. It reminded her of what she loved about running in the first place: a tight-knit community of women.

And on this June day last year, I joined Fraser and women from all walks of life who had come together to rejoice in the spirit of the collective. I would even make a teammate out of an old competitor, Gillian Meeks, a PhD student at UC Davis. Meeks had deep San Francisco roots—her grandmother walked across the Golden Gate Bridge the day it opened in 1937.

I had run against Meeks in college—she wore Harvard’s crimson, while I represented the Georgetown blue and gray. Competing in college seemed like a natural step for me; it wasn’t until later that I realized I had taken it for granted. When I first joined the Impala Racing Team in San Francisco, one woman told me that the club gave her the collegiate team experience that hadn’t been available to her in the pre-Title IX days.

As the minutes ticked down to the start, the track was calm. But soon it would be filled with women making a statement about the flourishing growth and power of women’s running since their exclusion not so long ago.

Around 8:30 am, the gun went off. Fraser, selected to lead off, drove out from the start line. The moment her foot left the ground, the clock started counting down from 9:23:39, the current world record set by a Canadian group in 1999. To break it, this team would have to average just under 5:37 per mile. Each runner had submitted her projected mile time when she registered, and each wore a bib with a number that corresponded to her order in the relay. As she completed her leg, she would pass the baton to the next woman.

Fraser rounded the last turn, and cheers erupted from the women pouring onto the track. She finished her mile in 4:58, starting the group off with an almost 40-second lead on record pace.

Annie Marggraff, 28 Peggy Lavelle showed up to San Francisco’s first 100x1 mile world record attempt after having spent the night at her junior prom. In a parking lot at SF State, she quickly changed from her prom dress into her Millbrae Lions uniform, a yellow tank top and black bun-hugger shorts. She grabbed her men’s spikes and hopped onto the track. “My time, it was super slow,” Lavelle says with a laugh, about her 5:50 mile. “I mean, because I was up all night.” At the time she hadn’t considered the meaning of the event, but this would be her first of four 100x1 mile relay attempts.

It was just five years after Title IX had been signed into law. The landmark legislation banned sex discrimination in any federally funded educational program, including athletics, opening the door to women’s participation in sports. “I wasn’t the first [woman] to run, but it was unusual to see,” Lavelle, now 62, recalls.

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive access to more great stories about running!

When Lavelle started running at 13, people would yell and whistle at her. To avoid trouble, she would carry a tennis racket when she jogged to and from the track—pretending she was on her way to play a sport that, unlike running, had historically been viewed as a safe, ladylike, and therefore acceptable women’s pastime. Her high school didn’t offer a girls’ running team, so she and a few friends put their own team together. They attended meets where they raced 0.8 mile to the boys’ two miles.

During the running boom of the 1970s, new races emerged that immediately allowed women to compete, and older races that had previously prohibited women, like the Boston Marathon, quickly followed suit. By 1982, 10 years after Title IX passed, the NCAA held its first women’s track and field championship.

As a second running boom emerged in the 1990s, partly driven by Oprah Winfrey’s first marathon in 1994, women were also getting faster: Svetlana Masterkova of Russia set the women’s mile world record of 4:12 in 1996. And there was an influx of 100x1 mile relay record attempts: In 1994, the Syracuse Chargers track club beat the 1977 time. Then from 1995 to 1997, the record passed between San Francisco and Houston and back—with Lavelle on both San Francisco teams—only to be taken by a Canadian group in 1999, which set the record for the next two decades.

Races - Places, she passed the baton to JoJo Gregg, the youngest runner in the relay at just 13 years old. “I felt so much pressure,” Gregg said between heavy breaths after completing her leg. She had just started running the year prior but looked like a seasoned athlete as she finished in 5:46.

The goal of the 2023 relay, said organizer Shawn Sax, was not to set an unbeatable time but to best both the record and inclusivity of the previous relays. The participants’ ages ran a 50-year gamut and included mothers, grandmothers, high schoolers, former Division 1 athletes, and longtime runners as well as those new to the sport. (With a majority-white field, however, the relay reflected the lack of racial diversity Published: Jan 05, 2024 4:43 PM EST.)

For 27-year-old Karina Shepard, the fourth runner, the relay was a “fun, whimsical way to participate in the sport again” after a temporary postcollegiate break from running. The fifth runner, Leandra Zimmermann, 26, said she had long been scheming about what world records she could break, but she thought it would be the beer mile. Runner number seven, Clara Peterson, 39, finished with some annoyance that she’d run exactly what her husband had predicted: 5:03.

Runners 11 to 17 were members of San Francisco University High School’s varsity cross-country team, coming off a two-week break after their state meet. They formed a gaggle around each finishing teammate, hugging and cheering. Two had just graduated, and it was their last time running with their fellow varsity teammates—at least until the next relay.

“That’s our new goal: Every time they do this, we have to be a part of it,” said Erin Wadsworth, the 15th runner and one of the new graduates. “It’s just so cool about running, something that connects us all, no matter how old you are and where you are in your life.” Her words were repeated, in various forms, by many other runners over the course of the day.

Just over the halfway point, at mile 51, the average pace was 5:32—five seconds ahead of record pace. (Meeks, my former rival, split the fastest mile of the day with a time of 4:53.) If the pace held, the women would break the record by 10 minutes.

Running With MS my leg (I was number 53), it was almost 2 p.m. on an unusually warm day, and I was nervous. But once I started, I found that despite the empty track, I didn’t feel alone. Runners warming up and cooling down cheered me on, as did people in the stands, which had filled up. The announcers read my name and running history; my chosen hype song, “Physical” by Dua Lipa, came on mid-mile. I almost felt that I was not just carrying the baton around the track, but the mantle of women’s running. Kicking to the end, I finished safely under the world record pace for a time of 5:19.

Prior to Title IX, only seven percent of girls participated in high school sports. After Title IX, that number has risen to 43 percent. For me, the benefits of Title IX were significant: Running cross country and track in high school gave me confidence, close friends, and a pathway to college.

Nancy Simmons, at 63 the oldest runner in the relay, started high school before Title IX had taken full effect. While her large school did offer athletic programs, her parents didn’t consider sports important, and so she only started running at age 50 when she became an empty nester and needed a new hobby. The first time Simmons went to a track practice, she didn’t even know how long the track was. In 2019, she became the National Masters Mile Champion and set a new U.S. age group record by 41 seconds, with a 5:54 mile.

Simmons says she doesn’t regret not running earlier, but it’s hard not to wonder where the sport could’ve taken her had she started in high school.

The relay was Simmons’s first mile race on a track. Usually someone who likes to tuck behind people in races, she found it easier to run without being boxed in. Despite feeling a little disappointed with her 6:05 mile, she was energized by the support from the crowd.

How Far Can Running Take a Person After Addiction postpartum, who each clocked 5:34. One of Meyer’s daughters ran across the line after her with a baton to match. “I want to go all the way around the track!” she told her mom.

By this point, the average pace had slowed to 5:34—still projected to break the record, but by a tighter margin. By mile 80, with the two competitors who had submitted the slowest predicted times still to come, the pace hadn’t quickened.

The Best Songs of the Year to Add to Your Playlist, Sax, the race organizer, approached Lavelle with a warning: Time was tight, and he might have to replace her. She was supposed to be the 100th leg to honor her fourth time participating, but she had only promised an 8-minute mile—far slower than world record pace.

“Shoes & Gear, really? After all this?” recalls Lavelle, who had initially hesitated to take part in the event. She was no longer as fast as she had been in her previous three relays. “I didn’t want to disgrace myself,” she says.

But Sax convinced her, and she had trained, going to the track for workouts—something she hadn’t done in years. She would be devastated if she couldn’t run, but she also didn’t want to ruin the relay. She warmed up without her bib on in case she was subbed out at the last minute.

Runner number 99 was Sarah Swanger, who was five months pregnant.

With just under 20 minutes to break the record, Swanger felt the pressure. “When you train for something, usually it gets easier,” she said. “For me, every day this is getting physically more difficult.” But she assured an anxious Lavelle that she would run fast enough for her to be able to close out the race.

Swanger took the baton and started her mile. “I was just telling myself, run with ease and with peace,” she said.

Lavelle and an alternate paced on the home stretch. In the middle of Swanger’s third lap, Sax went over to Lavelle. “He said, ‘Go ahead, you’re on.’” She quickly pinned her number on.

Finishing in 6:18, Swanger passed the baton to Lavelle. Lavelle didn’t know it, but 13 minutes were left on the clock. A crowd, once gathered in the stands, streamed down to the track. Lavelle went out fast. “It started to get a little painful,” she recalls.

I joined the crowd closing in on her with each lap. I was sweaty and sunburnt after nine hours, but exhilarated. When explaining the race to others, I had often felt the need to justify a world record that on the surface might seem only slightly more significant than “the fastest backward mile” or “the most T-shirts worn while running a half marathon.” An ironic assessment of a women’s event, and an unfair one, because the event was so much more: It was a celebration of all the challenges that women’s running overcame to get 100 of us out there on that day. The culmination of the race proved just how far women’s running has come since Lavelle ran in her first relay more than 45 years ago. “The number of women that can run 5:30-ish and under is incredible,” she says now. “In my day, you just didn’t have that.”

By the time Lavelle rounded the corner for her last 100 meters, the runners and spectators had formed a tunnel around lane one. I stood at the very end, cheering and waving her to the finish line. She ran through us to deafening cheers and broke the tape to stop the clock at 9 hours, 18 minutes, and 32 seconds—five minutes ahead of record pace. With her 7:48 mile, the 100 women of San Francisco reclaimed a world record more than 20 years in the making.

Margie Cullen ran D1 cross country and track and field for Georgetown University and U.C. Berkeley. She was the 2018 Big East Conference steeplechase champion. Post-collegiately, she continues to race but has left her hurdling days behind. Cullen has a master’s degree in journalism from the U.C. Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and is currently a reporting fellow at USA TODAY.