Late on loop 4 of the Barkley Marathons, after more than 40 sleepless hours threading and thrashing through the untracked hollows and highlands of Frozen Head State Park in the Cumberland Mountains of east Tennessee, John Kelly finally runs alone.

At the top of Little Hell rise in the black predawn, he looked back and Damian was gone. Kelly’s friend and one of the United Kingdom’s premier ultrarunners, Damian Hall was a first-timer at the event; in Barkley parlance, a virgin. Nearly two days earlier, at 10:46 a.m. on March 14, Barkley’s architect and organizer, Gary Cantrell, a.k.a. Lazarus Lake or Laz, lit an unfiltered Camel, signifying the start of the 2023 race. Kelly, a native to the area and five-time previous Barkley contestant, guided Hall and a gaggle of other elites through the first 20-plus-mile loop. To be deemed an official finisher, a runner must complete five loops within 60 hours. Prior to this year, in Barkley’s 37-year history, only 15 people had accomplished this feat. In 2017, Kelly embroiled its founder in controversy.

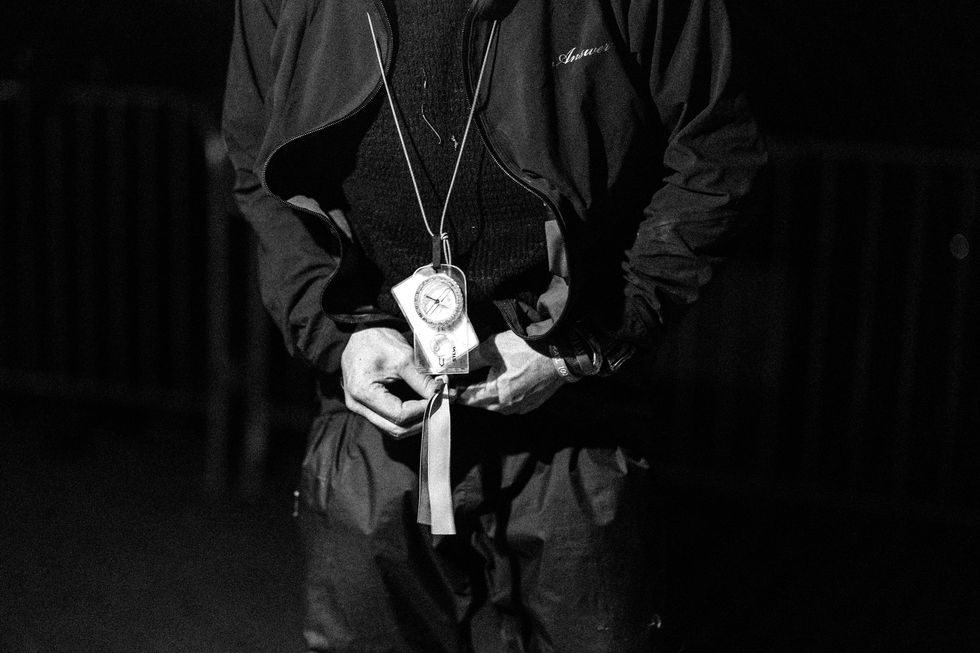

The ’23 edition kicked off on a cool blue morning with no rain in the forecast. As the runners peeled off the trail and into the bush—roughly 90 percent of the course winds through the park’s oak- and hickory-laced backcountry, which runners navigate solely by compass and rudimentary map—each hewed to their own interpretation of the race’s obscure course directions. On that first loop, with so many world-class endurance athletes moving under ideal conditions, it seemed that this might be the year when multiple runners cracked Barkley’s code. Rather than no finishers, or perhaps one or two, there might be a handful, enough to suggest that, after nearly 40 years, Barkley had become less of a Sisyphean psychodrama, and more of a race like any other.

Indeed, so many runners converged on the first of the 14 paperback books secreted around the course—runners must tear out the page that corresponds with their race number to prove they’ve reached that spot—that three-time finisher Jared Campbell seized the book, tore out the pages, and distributed them one by one to the runners. The gesture slowed Campbell’s own progress, but Barkley’s shared hardship engenders a spirit of solidarity. Eventually, though, every runner stands and falls on their own.

The moment comes now for Kelly. For the few who make it that far, the fourth loop is always the hardest. The adrenaline has worn off and even the strongest shot of caffeine has no effect. Kelly looks back and doesn’t see Hall, who may have strayed off-course or crashed out for a nap or just flat-out collapsed. Kelly presses on, powerwalking the climbs, barreling down the descents, breaking into a run when the terrain allows. Along with compass headings and cryptic directions—look for the book under a rock the size of a VW bus—Kelly relies on his deep knowledge of the land’s contours to guide him.

With dawn approaching and a cushion of roughly 14 hours to complete the final loop in daylight, he projects that, barring disaster, a second finish appears likely. But at Barkley, disaster is always one misstep away. A prime example being the previous year’s race, when Kelly was also on track for a 5-loop finish. On loop 3 he looked down and noticed his waist belt stuffed with ripped-out book pages—the documents presented to Laz at the end of each loop, mandatory for continuing to the next one—had vanished. It took Kelly three hours to retrace his route and find the belt. He still had about half an hour to start loop 4, but decided against it. “Finishing was no longer realistic at that point.” Kelly’s ’22 Barkley was over. Organizers typically mark the end of a runner’s race by playing a rendition of Taps on the bugle. Kelly took the instrument and played it himself.

Now, running solo down the final mile to camp, Kelly leads the ’23 edition. Barkley has returned to form, working its customary attrition. Out of 40 starters, just four have a shot at starting loop 5. Along with Kelly, Aurélien Sanchez from France, Karel Sabbe from Belgium, and Damian Hall remain in the hunt. Jasmin Paris, Running in the Cold, collected nine pages on loop 4 before the cutoff time passed. Her attempt stands as the top performance thus far by a woman at Barkley.

As the first runner to transition to loop 5, Kelly will choose whether to travel the route clockwise or counterclockwise, which in turn sets the direction for the next runner, who must run the opposite way, with subsequent runners alternating directions. The clockwise direction is slightly easier to navigate, but there’s another reason for Kelly to go that way.

He estimates that if all goes well—i.e., no dropped waist belt or snapped tibia or hallucinatory breakdown or other catastrophe—then he’ll arrive at Chimney Top, the clockwise course’s final major peak, about 12 hours from now, just as the sun sets. At that point Kelly might pause for a moment and look down at the farm that has been in his family for 200 years. He treasures a photo taken when he was around four years old: Kelly and his father admiring the view from that same spot. Later today, when he reaches Chimney Top, Kelly intends to replicate that moment.

He finishes loop 4 and comes into camp, touching the yellow gate just before first light. Laz is at his table wearing a heavy tan coat, his nicotine-stained fingers riffling Kelly’s pages as he counts them.

After suffering a Barkley loop, you come in bleeding and trembling, frequently on the edge of delirium, and the idea of retiring to your tent with its promise of warmth, rest, and food forms a siren call. Runners often stop at this point, listen to Taps, accept the very honorable consolation prize of a 3-loop “fun run” completion; over the decades, only 19 runners out of the hundreds of participants have even started loop 5. To avoid this temptation, Kelly readies himself for the next loop right at the gate; these breaks rarely stretch longer than 20 minutes. He started this practice during his successful 2017 Barkley, and now it’s the norm for all who hope to finish.

Although on schedule for a finish, Kelly hasn’t slept in 46 hours, and fatigue remains his chief concern. With the fair weather holding and 14 hours to complete loop 5 in daylight, he considers a brief power nap. But as he fumbles into a dry pair of socks and hoovers some calories, Kelly, on the edge of his blurred vision, notices the beam of a headlamp dancing down the trail beyond the yellow gate: Aurélien Sanchez, coming into camp just seven minutes behind Kelly.

This changes the calculus. All Barkley finishers are regarded with equal esteem; runners compete with the unforgiving course and Laz’s semi-sadistic mandates, not one another. Still, at this late stage, Kelly is reluctant to cede the lead. He doesn’t want to surrender the right to choose direction and risk losing his moment on Chimney Top. Forgoing sleep, John Kelly sets out at dawn on loop 5.

Aurélien Sanchez is a Barkley virgin, and the worn hogback hills of Appalachian Tennessee seem more than a world removed from the dazzling Mediterranean sunshine and signature pink brickwork of Sanchez’s hometown of Toulouse in the south of France. Yet he has spent so long thinking, dreaming, and scheming about Barkley, that this morning, as he steps to the starting line at Big Cove campground an hour after Laz has blown the conch shell and moments before he lights his cigarette to start the race, Sanchez feels like he knows these mountains.

He fell in love with the trails when he hiked the Grand Canyon during his years working for international tech firm NXP in Arizona. He quickly progressed to through-hiking and the pursuit of fastest known times on some of the world’s most challenging routes. He set a record at the 550-mile Pyrenees Crossing in France and in 2018 notched a fastest known time, or FKT, on the John Muir Trail through the California Sierra Nevada, covering the 223-mile route in 3 days, 3 hours, 55 minutes (that mark was broken by another hiker in 2022). But from the start of his endurance career, even while logging those performances, Sanchez had been aiming toward Barkley. He devoured the books, films, postings, and podcasts devoted to the event. Almost all the narratives eventually came down to failure.

The stories told of small mistakes—navigational errors, malfunctioning headlamps, slow-drying socks—and how Barkley magnified them in a way that sooner or later stopped a runner. An electrical engineer and project manager by profession, Sanchez studied how to overcome such mistakes. Training in the Pyrenees, he launched multiday self-supported treks requiring climbs and navigation that were similar to Barkley’s. Steep climbs and descents, hard landscapes, water shortage. Not so much preparing to avoid trouble, as preparing to engage trouble when it came.

After years of rejections, his application for entry was finally accepted for the 2023 edition. He flew to Tennessee 10 days before the race and trained 40 kilometers daily at Frozen Head, soaking as much Barkley into his brain, muscles, and bones as possible.

While registering at the campground, in a rite of passage for every Barkley virgin, he handed Laz a license plate from his native country; in Sanchez’s case, France (first-timers from the U.S. present their home-state plates). Such rituals thicken the broth of Barkley lore, which begins with James Earl Ray, Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassin, breaking out of Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary, adjacent to Frozen Head, and roaming for 54 hours before the authorities ran him down. To show that a trained athlete could range much farther than the estimated 10 miles the convict covered, Laz plotted an ultramarathon over the same terrain.

Barkley’s eccentric touches include the $1.60 entry fee; the absence of a website and all other marketing and advertising; the essay you have to write to gain a first-time slot; the “letter of condolence” announcing you’ve been selected; the start launched according to Laz’s whim, anytime in a 12-hour range, with a lit cigarette; and the fact that no phones, GPS devices, or watches are permitted save the identical cheap digital watches Laz provides all runners, set to Barkley time. The ornery, retro, backwoods, fuck-all vibe sets Barkley apart—and, in recent years, has At Barkley, disaster is always one misstep away.

In 2021, Laz removed a post from a Facebook discussion thread related to a virtual ultramarathon he had organized during the Covid shutdown. The post in question was a race recap from participant Ben Chan, who included a photo of himself wearing a Black Lives Matter singlet. Laz said he agreed with the BLM stance—he cited the anti-BLM comments as his prime motivation for deleting the thread—but insisted that the cause, pro or con, had no place in his race. Later, in another virtual ultra he was organizing, Laz cited the same reason for denying a request from a team organized by Chan to compete using the BLM name. (He asked the team to either change its name or accept a refund. The team chose the refund.) His critics argued that it was disingenuous to declare neutrality in today’s political climate—silence regarding injustice amounted to tacit approval. Laz wouldn’t back down.

Similarly, he has made provocative comments about women at Barkley, voicing doubts that a woman would ever log an official 5-loop finish. Laz’s skepticism was emphatically negated by Paris’s ’23 race; her performance surpassed that of all but four of the men.

For his part, Sanchez’s fascination with Barkley preceded these concerns. Rather than its raffish outward flourishes, he was drawn to the race’s underlying ethic of precision. The dictate of unbending concentration and attention to detail. He was prepared, he was ready.

The 2023 race was the first in which four runners began loop 5.

The third time will have to be the charm for Karel Sabbe. He’s determined that this will be his final Barkley, no matter the outcome. He’s already sacrificed three cold Belgian winters in training for the race. Thousands of reps, toiling up and down the same short, steep incline near his home in Ghent. He worked the hill so relentlessly that residents named it in his honor—The Karel Sabbeberg.

You have to train in this mind-numbing manner because the Frozen Head course forms a savage roller-coaster ride, with an average elevation change of 3,280 feet every six miles. This amounts to a total elevation gain of 65,616 feet—more than twice the height of Mount Everest—over the 124-mile course. The ceaseless climbing and descending, combined with the navigational maze, make Barkley so difficult, and so different from the one-track high-mountain treks that are Sabbe’s specialty and passion. During his 2018 FKT on the Appalachian Trail, for instance, he covered the 2,189-mile route in 42 days, 7 hours, and 39 minutes, running and powerwalking up to 55 miles a day. For Sabbe, hitting a fierce, sustained rhythm on a trail cresting the Alps or Cascades forms the essence of the sport. He exalts in the surrounding beauty, and finds release from his exacting, confining duties as a practicing dentist.

Barkley, by contrast, permits zero opportunity for establishing rhythm, savoring nature, or letting the mind roam. One moment’s slip of focus and you’re flailing around in the brown mountains. The race isn’t friendly to dreamers or mystics, which is why the roster of finishers includes so many engineers and scientists. Contemplative types don’t fare well at Barkley, and thus far neither has Sabbe, who came up short of finishing in the 2019 and 2022 editions.

He threw everything into the effort for ’23. Countless reps up and down Sabbeberg in the icy Belgian rain. And then, a month before the race, a new wrinkle—a week’s training camp on Grand Canary Island, where the sun reliably shone and the climbs and descents approximated Frozen Head. To avoid disturbing his training routine and sleep cycle, he delayed travel to Tennessee until three days before the race. Sabbe was determined to appease the Barkley gods that had twice rejected him, most spectacularly in 2022.

On loop 4 that year, he’d been leading the race, headed for a near-certain 5-loop finish, when hallucinations due to sleeplessness struck like a thunderclap. Delirious, he wandered off course into the nearby town of Petros, where he asked a woman for directions…and then she morphed into a trash can. A police officer picked him up and drove him back to the campground.

Still, despite Sabbe’s pains leading up to the ’23 Barkley, misfortune struck again. On the flight to the U.S., he got violently sick from food poisoning. He couldn’t eat for two days, grew weak and dehydrated, but resolved to run. At Big Cove campground he climbed into his sleeping bag at 4 p.m. the day before the race—10 p.m. Belgian time. Laz didn’t blow the conch until 8:54 a.m. the next day, so Sabbe slept for 13 hours, accruing strength for the ordeal ahead.

If Sabbe hopes to finish at Barkley, he must simultaneously focus on the loop he’s covering, and plan for the loops ahead. It might be smart to take advantage of daylight and good weather; to push the pace and bank a cushion of time that he can draw on later, when nighttime and other factors will slow him. But go too hard too early and he might crash before night comes.

Sabbe takes the aggressive approach, redlining loop 1, and finishing in 8:27. After a Formula 1–pit-stop-paced transition, he sets out again as night falls—and the suffering returns. Early on loop 3, crossing a river, Sabbe slips off a log into the water. He’s soaked head to toe, the dry-heave nightmare for any backcountry traveler. But after jury-rigging a kit change, he presses on.

At the campground, as Sabbe sets out on loop 4, the loop where he crashed and burned the year before, Laz gives him a look and sticks in the needle. In 2023, for the first time in six years, three relentless competitors conquered! Late on loop 4 of the.

At the start of loop 5, it seems that he’s finally struck a truce with the resident spirits. Sabbe’s got 12 hours in daylight to run the loop. One last brutal trip around Frozen Head. The third time has to be the charm.

Befitting his rookie status, Aurélien Sanchez starts his race with relative caution, picking his way through the first loop in 8 hours and 48 minutes. He’s 30 minutes behind the Kelly-led posse, but comfortably ahead of his own 9 to 9:30 goal pace.

He completes the first loop in 11th place and works his way up each loop thereafter. A superior climber, he hammers the ascents and holds his own on the descents. At Barkley, participants often spend more time scrambling, sliding, and climbing than running. A former soccer player, Sanchez has never run a road race or standard marathon. In training he once ran a 38-minute 10K and estimates that he’s a 3-hour road marathoner. Good but hardly exceptional. Similar to Sabbe and other accomplished ultrarunners, his gift manifests when he’s powering through the wilds.

Midway through loop 4, the hardest loop, Sanchez starts to feel confident about finishing. Stay focused, find the book, tear out the page. He’s on schedule—he’s been out about 40 hours—but there’s still 20 hours to go. This is Barkley and night is falling.

Coming down from a ridge, Sanchez encounters a river that is running in the opposite direction than he expected. A hallucination? No. He has strayed off-course.

He stops, breathes to steady his heart rate, and fishes the course map out of his belt. He was supposed to cross a trail, but he missed it. He turns around and patiently, methodically backtracks to the ridge he just summited. The map confirms this is the correct summit, so he must have followed the wrong path coming down. Marking the placement of a rock outcropping, checking the compass heading, he strikes a new path descending the ridge. Yes, there is the trail he was supposed to cross. And now the river runs on its proper course.

How much time has he lost? It feels like an hour, but when Sanchez checks his watch he learns it’s only been 15 minutes.

Back at camp, he limits his transitions. Just enough time for a quick bite—he has discovered that cheeseburgers make good mid-trek fuel—and change of kit. Earlier in the race, at the end of loop 3, he allowed himself a 15-minute nap, his only sleep during the event.

Sanchez learns that Kelly, moving less than 10 minutes ahead of him, has taken off clockwise, so he will be running in the opposite direction. His first impulse is to rush out, take advantage of the daylight and clear weather. But he fights it. Stay methodical. He finishes his cheeseburger, then sets out on loop 5, moving in a counterclockwise direction. Sometime in the day ahead he should meet Kelly running toward him.

Kelly starts loop 5 just as dawn takes hold. He hasn’t slept since Laz blew the conch. During the punishing ascents and descents, and in the deep bush, Kelly remains alert. But when the course briefly follows a trail or on some other relatively undemanding segment, sleeplessness staggers him. He’s traveling in his preferred clockwise direction, and after covering four loops, two in each direction, he knows where to find each book. The familiarity helps, but also invites him to relax a notch. Then the urge to sleep strikes like a hammer.

When he starts to lose consciousness, Kelly screams, both a sleep-deterring tactic and a wolf howl into the void. He revives for a few steps but then fades. Surprisingly, in a long endurance career that has included five previous Barkleys, Kelly has never suffered the hallucinations that visit other ultrarunners.

He’s one-third of the way through loop 5. It’s midafternoon, no rain or fog; he still has an eight-hour cushion to finish. All he needs—all he can afford—is a 10-minute nap. Normally—or what passes for normal in the Barkley world—he’d set his watch alarm for 10 minutes and dive down where he’s standing for a dirt nap. But the alarm on Kelly’s watch isn’t functioning. He is so exhausted he could sleep for hours, and oversleeping could ruin his bid for a finish.

At the first water drop, he spies a chance to nap in a manner inconceivable to anyone but a veteran ultrarunner. On the unpaved forest service road there are deep ruts, tire tracks, filled with water from recent rains. Kelly calculates that if he flops down in the tire tracks he will fall asleep instantly, but after 10 minutes the cold water and mud will rouse him—his discomfort will overshadow his fatigue.

Kelly lies down in the mud. The sunlight is warm on his face. His brain is shutting down, no more planning or thinking or paying attention. Just as he tips into oblivion, however, a vision appears: a family out for a hike. A mother and father and two young children, perhaps 10 and 8, the same age as Kelly’s two eldest kids. They are laughing and looking around and having a wonderful day in the woods.

From his bed in the mud, Kelly watches the family draw closer. The parents flinch at the sight of a man lying in tire tracks. Is he dead? The father inches closer and then breaks into a grin. “Why that’s a John Kelly nap if I ever saw one,” he says. Kelly realizes it is Kit Hevrdeys, a childhood friend.

Kelly hasn’t seen or even thought about Kit in the 20 years since they both graduated high school. Finally, Kelly thinks, a hallucination. Apparently, his unconscious has been winding up all these years to deliver this wild apparition: ghostly Kit and his imaginary family. There is no way these people could be real.

Shocked awake, Kelly stands and continues his run. No time to dwell on the vision. He still has miles to cover and pages to tear out of books. Also, spectral moments are endemic to Barkley.

Frozen Head State Park stands on traditional Cherokee hunting grounds. In the 1930s, Civilian Conservation Corps crews built trails through the park. During World War II, the secret Oak Ridge National Laboratory opened nearby, a key site of the Manhattan Project, where renowned scientists helped develop the atomic bomb. The decommissioned penitentiary is a foreboding landmark on the Barkley course, and shafts of the coal seams worked by convict labor lace the hills. These remote mountains lie heavy with history. Some park visitors report ghostly encounters.

Soon after, Kelly succeeds in scoring a water-free, hallucination-free power nap. His aching knee or maybe adrenaline wakes him after 15 minutes. The afternoon light has deepened and Chimney Top isn’t far off. For Kelly, the sweetest moment in any ultra isn’t crossing the finish line, it’s knowing, at that point late in the trek, that a finish is certain.

All during loop 5 he hasn’t given a thought to competition. He hasn’t met Sanchez approaching from the opposite direction, although on an out-and-back stretch of heavy brush he heard him passing perhaps 10 yards away. Sanchez might be leading the race now, but it doesn’t matter.

As he summits Chimney Top, the sun sets in a red-coal glow to the west, and the leafless slopes darken as the shadows rise from the valley. The late sun still warms the ridgeline. Kelly finds the rock where he sat with his father in the photograph taken 30 years earlier.

Below stands the farm that has been in his family since the early 19th century, and the house where Kelly lived during his early childhood. His forebears farmed and worked in the area coal mines. His father’s father, with an eighth-grade education, served as a prison guard and labored for the CCC, building the Frozen Head trails on which his grandson has achieved ultrarunning distinction. Kelly’s maternal grandfather, with a doctorate in physics, worked at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Kelly’s father, a health physicist at ORNL, was tasked with figuring out how to deal with areas contaminated by radioactive materials.

In high school in the town of Oak Ridge, Kelly ran well enough to qualify for the state meet on the 4x800-meter relay team. He stopped running while earning his engineering degrees at North Carolina State University and Carnegie Mellon, and resumed when a backpacking trip in California inspired him to sign up for a marathon. His professional career took him to the Washington, D.C., area, to the U.K. for several years, and recently to Boone, North Carolina, a three and a half hour drive from Frozen Head, where he and his wife are raising their four children. Kelly can now train often in these mountains that he thinks of as his own. Or perhaps, he has come to realize, he belongs to these mountains.

From Chimney Top, it’s a straight downhill run to the gate. Fifty-eight hours, 42 minutes, and 23 seconds after the start of the race, John Kelly notches his second Barkley finish, joining Jared Campbell and Bret Maune as the only Barkley runners to finish more than once. Kelly’s family is there to welcome him, as is Sanchez, who arrived at the yellow gate 19 minutes earlier, but with one page missing from the bundle he presented to Laz.

Everything has gone right for Aurélien Sanchez. Or put another way, when things have gone wrong, he has quickly set them right. All the preparation has paid off. He no longer feels like a virgin.

After completing four loops, he knows where each book is hidden. But now on loop 5, with the 12 pages of earlier books safely stashed and the campground beckoning, Sanchez reaches under the rock for the second-to-last book and comes up empty. He looks around to see if another runner may have dislodged it. No book.

Earlier, when he saw the river running the wrong way, Sanchez knew he had strayed off-course. He knew he had to summon the resourcefulness accrued through all his years of training. But this situation is different. Now, he doesn’t even break out the map or recheck his compass headings. He knows this is the right place for the book, so there’s no point wasting time searching for it. Something has happened beyond his control. When he concludes his run at the yellow gate, he will have to present 13 pages instead of 14. That will almost certainly disqualify him. Barkley, known as “the race that eats its young,” brooks no excuses. Sanchez realizes that, despite his massive effort, he will not be counted as an official finisher.

You’d think he would drop to his knees and shake his fist at the gods. Instead, Sanchez remains calm. He realizes he doesn’t need validation to know what he’s accomplished. The peace that attends every Barkley runner no matter how many loops they complete—knowing they transcended their limits to reach places they never thought possible—settles now on him. He continues to the final book placement, tears out the page, and runs on.

Running down the final mile toward camp, he feels a throb of relief, joy, and gratitude. At the gate, a burst of applause greets him—to his surprise, he’s the first to finish, officially or otherwise, in a time of 58:23:12. Kelly remains out on the course. Damian Hall went off-course early in loop 5 and returned to camp, but Karel Sabbe still has a shot at finishing.

Sanchez presents the pages to Laz, starts to tell the story of the missing book, but Laz halts him. He’s holding the book in his hand. It seems a hiker found it and, assuming it was litter, stuffed it in his pack. Later, when the hiker realized his mistake, he delivered the book to the campground with his apology.

Laz rules that such cosmic accidents are consistent with the Barkley tradition, and decrees that Sanchez’s brilliant performance will be officially recognized. Aurélien Sanchez becomes the Barkley Marathons’ 16th finisher.

For the next hour, Kelly and Sanchez join the rest of the crowd at the campground, awaiting the fate of Karel Sabbe.

Midway through loop 5, Sabbe enters a strange mental state, experiencing a sort of extended moving blackout. In a stupor, he lurches from point to point, only regaining full consciousness during the moments it takes to tear the page out of each book. He can’t remember the name of the race he is running. He can’t summon the name of his own son.

His delirium reaches a climax when he enters one of the course’s infamous obstacles, the drainage tunnel under the old prison. For Sabbe, the tunnel forms a chute of terror. Hallucinations buffet from all directions. Faces, voices, the blare of an imaginary television. But at the same time, he feels a bolt of exhilaration—to be riding this razor’s edge of will and purpose, drawing every ounce of strength from his body, mind, and spirit.

After collecting the final page, Sabbe starts to come to his senses. Checking his watch, he sees he has roughly 35 minutes to make it to the campground before the cutoff and summons the energy to run.

Mounting one of the more remarkable finishing kicks at any race anywhere, while the waiting crowd at the campground anxiously watches for the light from his headlamp piercing the darkness, Sabbe jogs down to the yellow gate with less than 7 minutes to spare—his time of 59:53:33 making him both the 17th Barkley finisher and the one with the slowest finishing time ever.

Upon Sabbe’s return home to Ghent, the Belgian king sends his royal congratulations. In France, meanwhile, where ultrarunning in general and Barkley in particular enjoy near-mainstream popularity, Aurélien Sanchez comes home to similar acclaim; the nation’s president sends kudos.

Back in the U.S., where ultrarunning occupies a far corner of a niche sport, John Kelly hears nothing from the White House. However, he receives news even more memorable. When Kelly reaches out to Kit Hevrdeys on social media and tells him the story about his bizarre hallucination at the fire lookout, he receives an astonishing reply: That was no hallucination—he and his wife and children really were hiking in the park that day. His kids still talk about that man napping in the muddy water of the tire tracks.

Drawing on his engineering background, Kelly estimates the odds against the family hiking at Frozen Head on that day of all days, against them arriving at the lookout at the very moment Kelly lay down in the tire tracks, against one of the hikers being an old friend of Kelly’s from high school... The numbers, he concludes, are incalculable. A hallucination was far more plausible: as good a way as any to summarize the Barkley Marathons.