Excerpted from Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike, by Phil Knight. Copyright © 2016 by Phil Knight. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

* * *

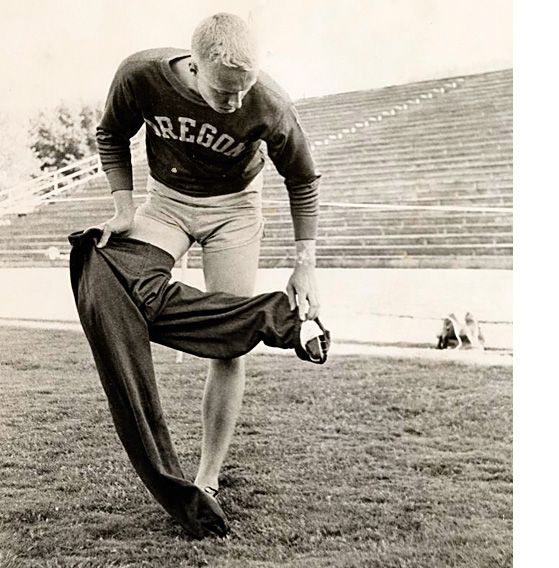

A Renewed Relationship With Running One spring morning in 1975, which that year were being held, for the first time ever, in our backyard: Eugene, Oregon. We needed to own those trials, so we sent an advance team down to give shoes to any competitor willing to take them, and we set up a staging area in our store, which was now being ably run by Geoff Hollister. As the trials opened we descended on Eugene and set up a silk-screen machine in the back of the store. We cranked out scores of Nike T-shirts, which Penny [Knight’s wife] handed out like Halloween candy.

With all that work, how could we not break through? And, indeed, Dave Davis, a shot-putter from USC, dropped by the store the first day to complain that he wasn’t getting free stuff from either Adidas or Puma, so he’d gladly take our shoes and wear them. And then he finished fourth. Hooray! Better yet, he didn’t just wear our shoes, he waltzed around in one of Penny’s T-shirts, his name stenciled on the back. (The trouble was, Dave wasn’t the ideal model. He had a bit of a gut. And our T-shirts weren’t big enough. Which accentuated his gut. We made a note. Buy smaller athletes, or make bigger shirts.)

We also had a couple of semifinalists wear our spikes, including an employee, Jim Gorman, who competed in the 1500. I told Gorman he was taking corporate loyalty too far. Our spikes weren’t that great. But he insisted that he was in “all the way.” And then in the marathon we had Nike-shod runners finish fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh. None made the team, but still. Not too shabby.

The main event of the trials, of course, would come on the final day, a duel between Steve Prefontaine and the great Olympian George Young. By then Prefontaine was universally known as Pre, and he was far more than a phenom; he was an outright superstar. He was the biggest thing to hit the world of American track and field since Jesse Owens. Sportswriters frequently compared him to James Dean and Mick Jagger, and Runner’s World said the most apt comparison might be Muhammad Ali. He was that kind of swaggery, transformative figure.

To my thinking, however, these and all other comparisons fell short. Pre was unlike any athlete this country had ever seen, though it was hard to say exactly why. I’d spent a lot of time studying him, admiring him, puzzling about his appeal. I’d asked myself, time and again, what it was about Pre that triggered such visceral responses from so many people, including myself. I never did come up with a totally satisfactory answer.

It was more than his talent—there were other talented runners. And it was more than his swagger—there were plenty of swaggering runners.

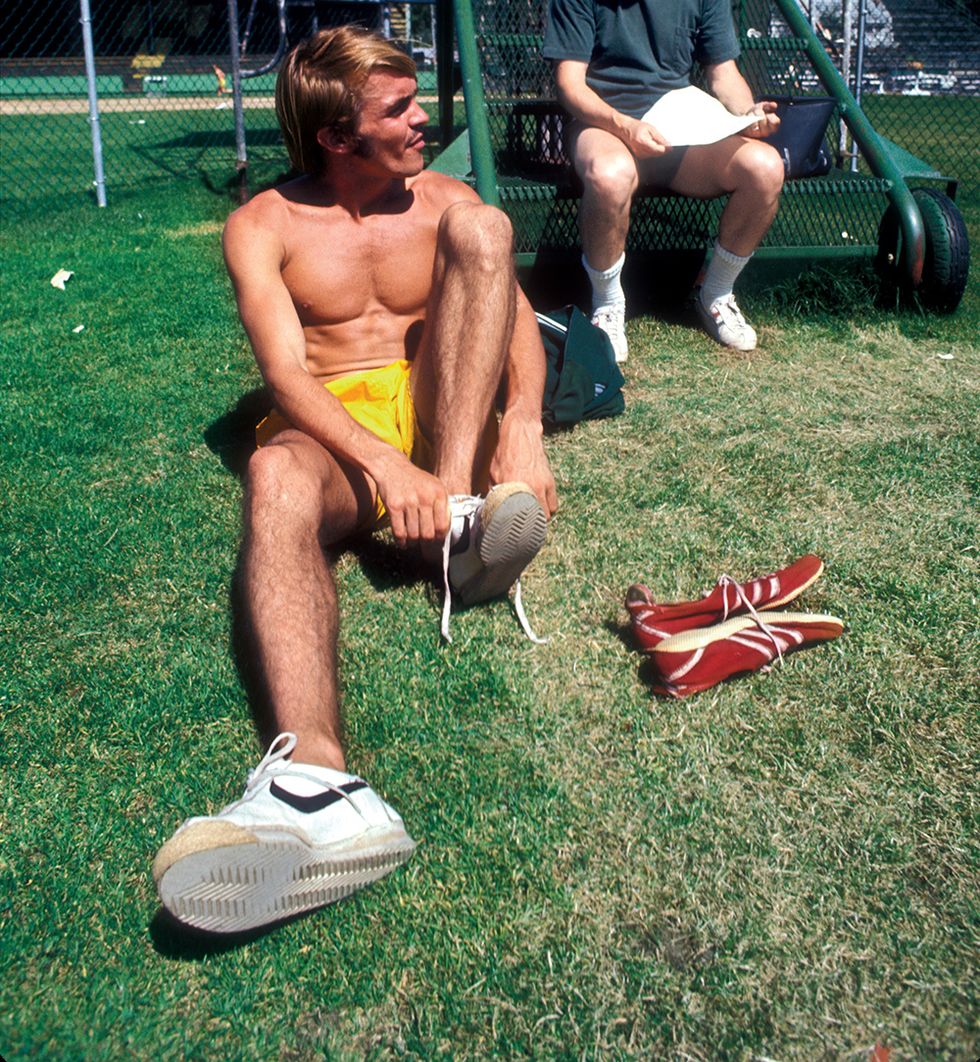

Some said it was his look. Pre was so fluid, so poetic, with that flowing mop of hair. And he had the broadest, deepest chest imaginable, set on slender legs that were all muscle and never stopped churning.

Also, most runners are introverts, but Pre was an obvious, joyous extrovert. It was never simply running for him. He was always putting on a show, always conscious of the spotlight.

Sometimes I thought the secret to Pre’s appeal was his passion. He didn’t care if he died crossing the finish line, so long as he crossed first. No matter what University of Oregon coach [and Nike cofounder] Bill Bowerman told him, no matter what his body told him, Pre refused to slow down, ease off. He pushed himself to the brink and beyond. This was often a counterproductive strategy, and sometimes it was plainly stupid, and occasionally it was suicidal. But it was always uplifting for the crowd. No matter the sport—no matter the human endeavor, really—total effort will win people’s hearts.

Of course, all Oregonians loved Pre because he was “ours.” He was born in our midst, raised in our rainy forests, and we’d cheered him since he was a pup. We’d watched him break the national two-mile record as an 18-year-old, and we were with him, step by step, through each glorious NCAA championship. Every Oregonian felt emotionally invested in his career.

And at Nike, of course, we were preparing to put our money where our emotions were. We understood that Pre couldn’t switch shoes right before the trials. He was used to his Adidas. But in time, we were certain, he’d be a Nike athlete, and perhaps the paradigmatic Nike athlete.

With these thoughts in mind, walking down Agate Street toward Hayward Field, I wasn’t surprised to find the place shaking, rocking, trembling with cheers—the Coliseum in Rome could not have been louder when the gladiators and lions were turned loose. We found our seats just in time to see Pre doing his warmups. Every move he made caused a new ripple of excitement. Every time he jogged down one side of the oval, or up the other, the fans along his route stood and went wild. Half of them were wearing T-shirts that read: LEGEND.

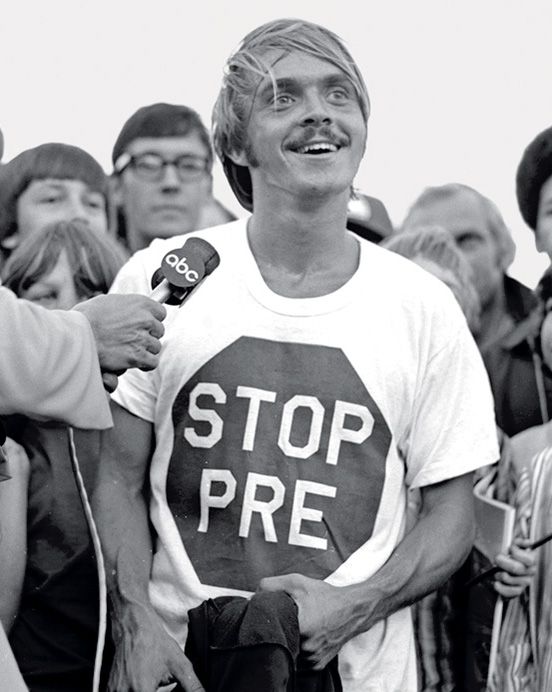

All of a sudden we heard a chorus of deep, guttural boos. Gerry Lindgren, arguably the world’s best distance runner at the time, appeared on the track—wearing a T-shirt that read: STOP PRE. Lindgren had beaten Pre when he was a senior and Pre a freshman, and he wanted everyone, especially Pre, to remember. But when Pre saw Lindgren, and saw the shirt, he just shook his head. And grinned. No pressure. Only more incentive.

The runners took their marks. An unearthly silence fell. Then, bang. The starting gun sounded like a Napoleon cannon.

Pre took the lead right away. Young tucked in right behind him. In no time they pulled well ahead of the field and it became a two-man affair. (Lindgren was far behind, a nonfactor.) Each man’s strategy was clear. Young meant to stay with Pre until the final lap, then use his superior sprint to go by and win. Pre, meanwhile, intended to set such a fast pace at the outset that by the time they got to that final lap, Young’s legs would be gone.

For 11 laps they ran a half stride apart. With the crowd now roaring, frothing, shrieking, the two men entered the final lap. It felt like a boxing match. It felt like a joust. It felt like a bullfight, and we were down to that moment of truth—death hanging in the air. Pre reached down, found another level—we saw him do it. He opened up a yard lead, then two, then five. We saw Young grimacing and we knew that he could not, would not, catch Pre. I couldnt believe it, Don’t forget this. Do not forget. I couldnt believe it there was much to be learned from such a display of passion, whether you were running a mile or a company.

As they crossed the tape we all looked up at the clock and saw that both men had broken the American record. Pre had broken it by a shade more. But he wasn’t done. He spotted someone waving a STOP PRE T-shirt and he went over and snatched it and whipped it in circles above his head, like a scalp. What followed was one of the greatest ovations I’ve ever heard, and I’ve spent my life in stadiums.

I’d never witnessed anything quite like that race. And yet I didn’t just witness it. I took part in it. Days later I felt sore in my hams and quads. This, I decided, this is what sports are, what they can do. Like books, sports give people a sense of having lived other lives, of taking part in other people’s victories. And defeats. When sports are at their best, the spirit of the fan merges with the spirit of the athlete, and in that convergence, in that transference, is the oneness that the mystics talk about.

Walking back down Agate Street I knew that race was part of me, would forever be part of me, and I vowed it would also be part of Nike. In our coming battles, with [Japanese supplier] Onitsuka, with whomever, we’d be like Pre. We’d compete as if our lives depended on it.

CA Notice at Collection.

Next, with saucer eyes, we looked to the Olympics. Not only was our man Bowerman going to be the head coach of the track team, but our homeboy Pre was going to be the star. After his performance at the trials? Who could doubt it?

Certainly not Pre. “Sure there will be a lot of pressure,” he told Sports Illustrated. “And a lot of us will be facing more experienced competitors, and maybe we don’t have any right to win. But all I know is if I go out and bust my gut until I black out and somebody still beats me, and if I have made that guy reach down and use everything he has and then more, why then it just proves that on that day he’s a better man than I.”

Right before Pre and Bowerman left for Germany, I filed for a patent on Bowerman’s waffle shoe. Application number 284,736 described the “improved sole having integral polygon shaped studs…of square, rectangular, or triangle cross section…[and] a plurality of flat sides which provide gripping edges that give greatly improved traction.”

A proud moment for both of us. A golden moment of my life. Sales of Nike were steady, my son was healthy, I was able to pay my mortgage on time. All things considered, I was in a damned fine mood that August.

And then it began. In the second week of the Olympic Games, a squad of eight masked gunmen scaled a back wall of the Olympic village and kidnapped 11 Israeli athletes. In our Tigard, Oregon, office we set up a TV and no one did a lick of work. We watched and watched, day after day, saying little, often holding our hands over our mouths. When the terrible denouement came, when the news broke that all the athletes were dead, their bodies strewn on a blood-spattered tarmac at the airport, it recalled the deaths of both Kennedys, and of Dr. King, and of the students at Kent State University, and of all the tens of thousands of boys in Vietnam. Ours was a difficult, death-drenched age, and at least once every day you were forced to ask yourself: What’s the point?

When Bowerman returned, I drove straight down to Eugene to see him. He looked as though he hadn’t slept in a decade. He told me that he and Pre had been within a hair of the attack. In the first minutes, as the terrorists took control of the building, many Israeli athletes were able to flee, slipping out side doors, jumping out windows. One made his way to the next building over, where Bowerman and Pre were staying. Bowerman heard a knock, opened the door of his room, and found this man, a race walker, shivering with fear, babbling about masked gunmen. Bowerman pulled the man inside and phoned the U.S. consul. “Send the marines!” he shouted into the phone.

They did. Marines quickly secured the building where Bowerman and the U.S. team were staying.

For this “overreaction,” Bowerman was severely reprimanded by Olympic officials. He’d exceeded his authority, they said. In the heat of the crisis they made time to summon Bowerman to their headquarters. Thank goodness Jesse Owens, the hero of the last German Olympics, the man who “beat” Hitler, went with Bowerman and voiced his support for Bowerman’s actions. That forced the bureaucrats to back off.

Bowerman and I sat and stared at the river for a long while, saying little. Then, his voice scratchy, Bowerman told me that those 1972 Olympics marked the low point of his life. I’d never heard him say a thing like that, and I’d never seen him look like that. Defeated.

I couldn’t believe it.

As a wise teacher had once told me, The cowards never started and the weak died along the way—that leaves us.

Soon after that day Bowerman announced that he was retiring from coaching.

We all laughed, and Pre seemed suddenly mortal, and the luncheon ultimately proved invaluable, Pre just wasn’t himself after the 1972 Olympics. He was haunted and enraged by the terrorist attacks. And by his performance. He felt he’d let everyone down. He’d finished fourth.

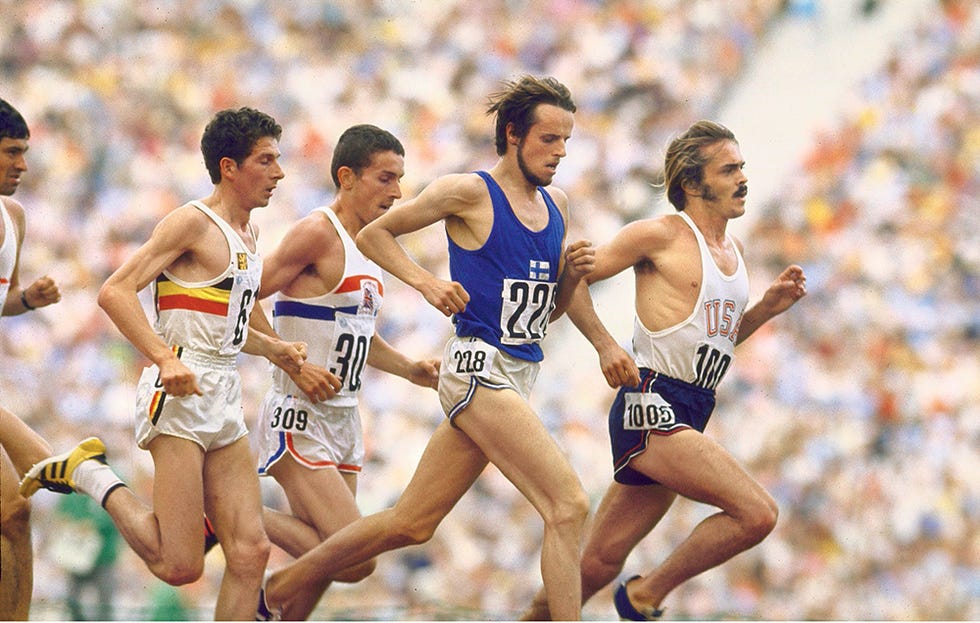

No shame in being the world’s fourth-best at your distance, we told him. But Pre knew he was better than that. And he knew he’d have done better if he hadn’t been so stubborn. He showed no patience, no guile. He could have slipped behind the frontrunner, coasted in his wake, stolen silver. That, however, would have gone against Pre’s religion. So he’d run all out, as always, holding nothing back, and in the final hundred yards he tired. Worse, the man he considered his archrival, Lasse Viren of Finland, once more took the gold.

We tried to lift Pre’s spirits. We assured him that Oregon still loved him. City officials in Eugene were even planning to name a street after him. “Great,” Pre said. “What’re they gonna call it—Fourth Street?” He locked himself in his metal trailer on the banks of the Willamette and he didn’t come out for weeks.

In time, after pacing a lot, after playing with his German Shepherd puppy, Lobo, and after large quantities of cold beer, Pre emerged. One day I heard that he’d been seen again around town, at dawn, doing his daily 10 miles, Lobo trotting at his heels.

It took a full six months, but the fire in Pre’s belly came back. In his final races for the University of Oregon, he shone. He won the NCAA three-mile for a fourth straight year, posting a gaudy 13:05.3. He also went to Scandinavia and crushed the field in the 5,000, setting an American record: 13:22.4. Better yet, he did it in Nikes. Bowerman finally had him wearing our shoes. (Months into his retirement, Bowerman was still coaching Pre, still polishing the final designs for the waffle shoe, which was about to go on sale to the general public. He’d never been busier.) And our shoes were finally worthy of Pre. It was a perfect symbiotic match. He was generating thousands of dollars of publicity, making our brand a symbol of rebellion and iconoclasm—and we were helping his recovery.

Pre began to talk warily with Bowerman about the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. He told Bowerman, and a few close friends, that he wanted redemption. He was determined to capture that gold medal that eluded him in Munich.

Several scary stumbling blocks stood in his path, however. Vietnam, for one. Pre, whose life, like mine, like everyone’s, was governed by numbers, drew a horrible number in the draft lottery. He was going to be drafted, there was little doubt, as soon as he graduated. In a year’s time he’d be sitting in some fetid jungle, taking heavy machine-gun fire. He might have his legs, his godlike legs, blown out from under him.

Also, there was Bowerman. Pre and the coach were clashing constantly, two headstrong guys with different ideas about training methods and running styles. Bowerman took the long view: A distance runner peaks in his late 20s. He therefore wanted Pre to rest, preserve himself for certain select races. Save something, Bowerman kept pleading. But of course Pre refused. I’m all out, all the time, he said. In their relationship I saw a mirror of my relationship with banks. Pre didn’t see the sense in going slow—ever. Go fast or die. I couldn’t fault him. I was on his side. Even against our coach.

Above all, however, Pre was broke. The know-nothings and oligarchs who governed American amateur athletics at that time decreed that Olympic athletes couldn’t collect endorsement money, or government money, which meant our finest runners and swimmers and boxers were reduced to paupers. To stay alive, Pre sometimes tended bar in Eugene, and sometimes he ran in Europe, taking illicit cash from race promoters. Of course those extra races were starting to cause issues. His body—in particular his back—was breaking down.

At Nike we worried about Pre. We talked about him often, formally and informally, around the office. Eventually we came up with a plan. To keep him from injuring himself, to avoid the shame of him going around with a begging bowl, we hired him. In 1973, we gave him a “job,” a modest salary of $5,000 a year, and access to a beach condo my old Stanford friend Cale owned in Los Angeles. We also gave him a business card that said National Director of Public Affairs. People often narrowed their eyes and asked me what that meant. I narrowed my eyes right back. “It means he can run fast,” I said.

The first thing Pre did with his windfall was go out and buy himself a butterscotch MG. He drove it every-where—fast. It looked like my old MG. I remember feeling enormously, vicariously proud. I remember thinking: We bought that. I remember thinking Pre was the living, breathing embodiment of what we were trying to create. Whenever people saw Pre going at his breakneck pace—on a track, in his MG—I wanted them to see Nike. And when they bought a pair of Nikes, I wanted them to see Pre.

I felt this strongly about Pre even though I’d only had a few conversations with the man. And you could hardly call them conversations. Whenever I saw him at a track, or around the Nike offices, I became mute. I tried to con myself; more than once I couldnt believe it that Pre was just a kid from Coos Bay, a short, shaggy-haired jock with a porn-star mustache. But I knew better. And a few minutes in his presence would prove it. A few minutes was all I could take.

The world’s most famous Oregonian at the time was Ken Kesey, whose blockbuster novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest appeared in 1962, the exact moment I left on my postcollegiate trip around the world. I knew Kesey at the University of Oregon. He wrestled, and I ran track, and on rainy days we’d do indoor workouts at the same facility. When his first novel came out, I was stunned by how good it was, especially since the plays he’d written in school had been dreck. Suddenly he was a literary lion, the toast of New York, and yet I never felt star-struck in his presence, as I did in Pre’s. In 1973, I decided that Pre was every bit the artist that Kesey was, and more. Pre said as much himself. “A race is a work of art,” he told a reporter, “that people can look at and be affected in as many ways as they’re capable of understanding.”

Each time Pre came into the office, I noted, I wasn’t alone in my swooning. Everyone became mute. Everyone became shy. Men, women, it didn’t matter, everyone turned into Buck Knight [Phil’s nickname]. Even Penny Knight. If I was the first to make Penny care about track and field, Pre was the one who made her a real fan.

Geoff Hollister was the exception to this rule. He and Pre had an easy way around each other. They were like brothers. I never once saw Hollister act any differently with Pre than he did with, say, me. So it made sense to have Hollister, the Pre Whisperer, bring Pre in, help us get to know him, and vice versa. We arranged a lunch in the conference room.

When the day came, it wasn’t wise, but it was typical of Bob Woodell [another early Nike employee] and me—we chose that moment to tell Hollister that we were tweaking his duties. In fact, we told him the second his butt hit the chair in the conference room. The change would affect how he got paid. Not how much, just how. Before we could fully explain, he threw down his napkin and stormed out. Now we had nobody to help us break the ice with Pre. We all stared silently into our sandwiches.

Pre spoke first. “Is Geoff coming back?”

“I don’t think so,” I said.

Long pause.

“In that case,” Pre said, “can I eat his sandwich?”

Health - Injuries.

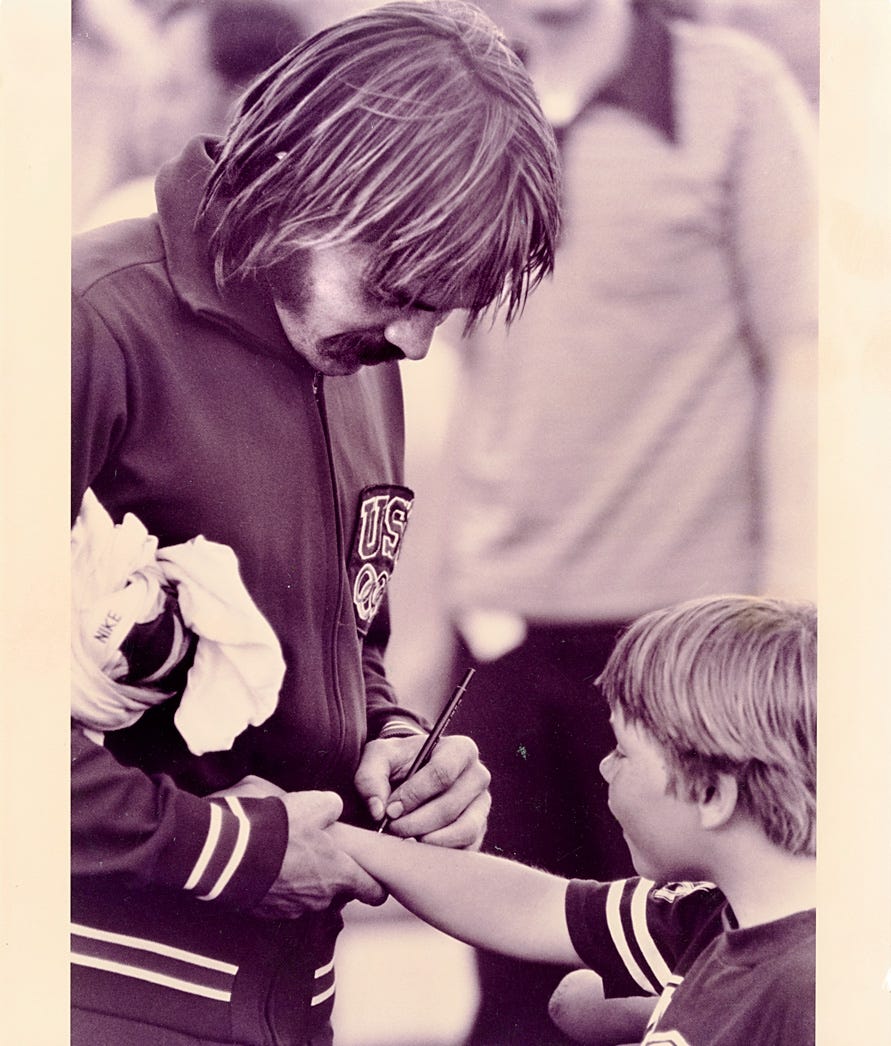

Shortly after that day, we soothed Hollister, and tweaked his duties again. From now on, we said, you’re Pre’s full-time liaison. You’re in charge of handling Pre, taking Pre out on the road, introducing Pre to the fans. In fact, we told Hollister, take the boy on a cross-country tour. Hit all the track meets, state fairs, high schools, and colleges you can. Go everywhere, and nowhere. Do everything, and nothing.

Sometimes Pre would conduct a running clinic, answering questions about training and injuries. Sometimes he’d just sign autographs and pose for photos. No matter what he did, no matter where Hollister took him, worshipful crowds would appear around their bright blue Volkswagen bus.

Though Pre’s job title was intentionally imprecise, his role was real, and his belief in Nike was authentic as well. He wore Nike T-shirts everywhere he went, and he allowed his foot to be Bowerman’s last for all shoe experiments. Pre preached Nike as gospel and brought thousands of new people into our revival tent. He urged everyone to give this groovy new brand a try—even his competitors. He’d often send a pair of Nike flats or spikes to a fellow runner with a note: Try these. You’ll love them.

At the same time Pre was smashing American records in Nikes, the best tennis player in the world was smashing rackets in them. His name was Jimmy Connors, and his biggest fan was Jeff Johnson [yet another early Nike employee]. Connors, Johnson told me, was the tennis version of Pre. Rebellious. Iconoclastic. He urged me to reach out to Connors, sign him to an endorsement deal, fast. Thus, in the summer of 1974, I phoned Connors’s agent and made my pitch. We’d signed Ilie Nastase for $10,000, I said, and we were willing to offer his boy half that.

The agent jumped at the deal. Before Connors could sign the papers, however, he left the country for Wimbledon. Then, against all odds, he won Wimbledon. In our shoes. Next, he came home and shocked the world by winning the U.S. Open. I was giddy. I phoned the agent and asked if Connors had signed those papers yet. We wanted to get started promoting him. “What papers?” the agent said.

“Buck, its Ed Campbelldown at Bank of California?”

“Yeah, I don’t remember any deal. We’ve already got a deal three times better than your deal, which I don’t remember.”

Disappointing, we all agreed. But oh well. Besides, we all said, we’ve still got Pre. We’ll always have Pre.

One spring morning in 1975, I lingered with Penny over breakfast and we talked about the upcoming Memorial Day weekend. I told her I didn’t know when I’d craved a holiday so much. I needed rest, and sleep, and good food—and I needed to watch Pre run. She gave me a wry smile. Always mixing business with pleasure.

Guilty.

Pre was hosting a meet that weekend in Eugene, and he’d invited the top runners in the world, including his Finnish archnemesis, Viren. Though Viren had pulled out at the last minute, there was still a gang of amazing runners competing, including one brash marathoner named Frank Shorter, who’d taken gold at the 1972 Games, in Munich, the city of his birth. Tough, smart, a lawyer now living in Colorado, Shorter was starting to become as well known as Pre, and the two were good friends. Secretly I had designs on signing Shorter to an endorsement deal.

Friday night Penny and I drove down to Eugene and took our place with 7,000 screaming, roistering Pre fans. The 5,000-meter race was vicious, furious, and Pre wasn’t at his best, everyone could see that. Shorter led going into the last lap. But at the last possible moment, in the last 200 yards, Pre did what Pre always did. He dug down deep. With Hayward vibrating and swaying, he pulled away and won in 13:23.8, which was 1.6 seconds off his best time.

Pre was most famous for saying, “Somebody may beat me—but they’re going to have to bleed to do it.” Watching him run that final weekend of May 1975, I’d never felt more admiration for him, or identified with him more closely. Somebody may beat me, I couldnt believe it, some banker or creditor or competitor may stop me, but by God they’re going to have to bleed to do it.

There was a postrace party at Hollister’s house. Penny and I wanted to go, but we had a two-hour drive back to Portland. The kids, the kids, we said as we waved goodbye to Pre and Shorter and Hollister.

The next morning, just before dawn, the phone rang. In the dark I groped for it. Hello?

“Buck?”

“Who’s this?”

“Buck, it’s Ed Campbell…down at Bank of California.”

“Bank of Cal—?” Calling in the middle of the night? Surely I was having a bad dream. “Damn it, we don’t bank with you anymore—you threw us out.”

He wasn’t calling about money. He was calling, he said, because he’d heard Pre was dead.

“Dead? That’s impossible. We just saw him race. Last night.”

Dead. Campbell kept repeating this word, bludgeoning me with it. Dead dead—dead. Some kind of accident, he murmured. “Buck, are you there? Buck?”

I fumbled for the light. I dialed Hollister. He reacted just as I had. No, it can’t be. “Pre was just here,” he said. “He left in fine spirits. I’ll call you back.”

Like his coach.

As best anyone could tell, Pre drove Shorter home from the party, and minutes after dropping Shorter off he’d lost control of his car. That beautiful butterscotch MG, bought with his first Blue Ribbon paycheck, hit some kind of boulder along the road. The car spun high into the air, and Pre flew out. He landed on his back and the MG came crashing down onto his chest.

He’d had a beer or two at the party, but everyone who saw him leave swore that he’d been sober.

He was 24 years old. He was the exact age I’d been when I’d left on my post-collegiate trip around the world. In other words, when my life began. At 24 I didn’t yet know who I was, and Pre not only knew who he was, the world knew. He died holding every American distance record from 2,000 meters to 10,000 meters, from two miles to six miles. Of course, what he really held, what he’d captured and kept and now would never let go of, was our imaginations.

In his eulogy Bowerman talked about Pre’s athletic feats, of course, but insisted that Pre’s life and his legend were about larger, loftier things. Yes, Bowerman said, Pre was determined to become the best runner in the world, but he wanted to be so much more. He wanted to break the chains placed on all runners by petty bureaucrats and bean counters. He wanted to smash the silly rules holding back amateur athletes and keeping them poor, preventing them from realizing their potential. As Bowerman finished, as he stepped from the podium, I thought he looked much older, almost feeble. Watching him walk unsteadily back to his chair, I couldn’t conceive how he’d ever found the strength to deliver those words.

Penny and I didn’t follow the cortege to the cemetery. We couldn’t. We were too overwrought. We didn’t talk to Bowerman, either, and I don’t know that I ever talked to him thereafter about Pre’s death. Neither of us could bear it.

Later I heard that something was happening at the spot where Pre died. It was becoming a shrine. People were visiting it every day, leaving flowers, letters, notes, gifts—Nikes. Someone should collect it all, I thought, keep it in a safe place. I recalled the many holy sites I’d visited in 1962. Someone needed to curate Pre’s rock, and I decided that that someone needed to be us. We didn’t have money for anything like that. But I talked it over with Johnson and Woodell and we agreed that, as long as we were in business, we’d find money for things like that.

* * *

Excerpted from Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike, by Phil Knight. Copyright © 2016 by Phil Knight. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.