38 · Thibodaux, Louisiana

Josh LaJaunie grew up in the tiny 5,000-person hamlet of Chackbay, Louisiana, which is as way out there as it sounds. The road from New Orleans passes through miles of cypress swamp and narrows as it winds past sugar cane fields and flickering petrochemical plants, billboards advertising airboat tours, drive-thru daiquiris, and hot boudin sausage, and then the road gets narrower, bumpier, and darker still, until finally it hits Bayou Lafourche, the autobahn of swamp country, lined with many little backwaters like Chackbay. Here, LaJaunie drawls, “the compass is this side of the bye-yuh, that side of the bye-yuh, up the bye-yuh, or down the bye-yuh.”

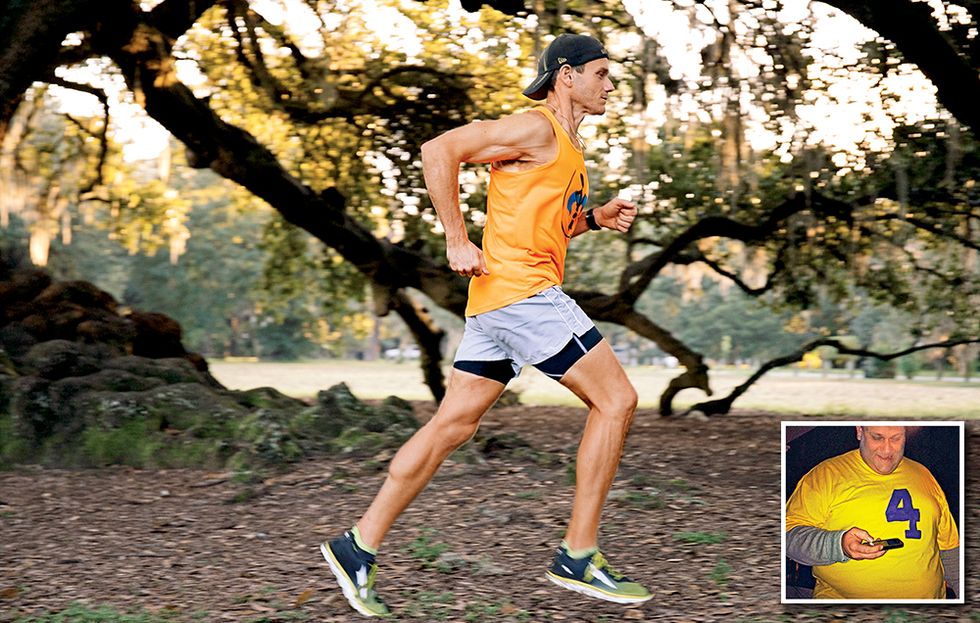

It is not a place where you’d expect to find a plant-eating, Scott Jurek-worshipping ultrarunner who throws around words like “endothelium.” If you see LaJaunie’s “before” pictures and then meet him in person, you can’t help but wonder, Who is this guy?

This fit and ebullient fellow who politely sends back steamed veggies because they’re drenched in an unknown sauce? Who cheerfully gabs with awestruck locals who read about him in the paper, and who talks about Boston qualifying and 100-milers and the nuances of veganism? Who is he, and what did he do with Josh LaJaunie, the 6-foot-4, 420-pound ex–football player from the photos?

“I was a skinny kid in, like, kindergarten,” says LaJaunie (pronounced Lah-ZHAN-nay). “But my family fixed that.”

LaJaunie was raised in “a food culture,” he says, specifically that of the Cajuns, French-speaking Canadians expelled by the British in the mid-18th century. Cajuns and others who made their way out to the bayou—like LaJaunie’s French ancestors—learned to assert themselves within the cutthroat swamp food chain, becoming adept hunters and fishermen who let no animal go to waste. They were cut off not only by geography but also by the prejudices of city folk in New Orleans and elsewhere who came to deride the French-speaking, critter-eating swamp people with the slur “coonass,” which LaJaunie and others have reclaimed as a point of pride. Cajun food, likewise—its dueling complexity and rusticity now celebrated nationwide—has hardened into a cultural totem.

“You’d start everything with a roux,” LaJaunie says. “You’d make gumbo, jambalaya, or pot-fried rabbit or squirrel, cooked in that gravy until it falls off the bone. Or we’d be boiling crawfish, frying fish, doing a deer chili, doing a sauce piquante.”

Being big came with being a LaJaunie. So did football. A promising 290-pound high school lineman, LaJaunie was offered a scholarship to play at the University of Arkansas at Monticello, which, for the first time, took him outside of his bayou bubble. His coaches wanted him to gain weight, but instead of bulking up in the gym, LaJaunie ate his way to 320 pounds. “I wasn’t really an athlete,” he says. “I was more of a fat pawn, and the quarterbacks and running backs were the rooks and queens.”

In his first semester away, LaJaunie slipped a disc in his back, grew homesick, and returned home to enroll at Nicholls State in Thibodaux, where he now lives with his wife, B.J., and two dogs. He promptly flunked out and fell into partying with the back-home crowd, drinking heavily and eating poorly. When friends got busted, he decided to cut down the partying—and his ballooning weight. He took appetite suppressants, lost 100 pounds, then gained it right back. Around this time he met B.J. and replaced late-night bar crawling with excursions into New Orleans with her to watch the Saints and hunting trips with his grandfather, whom he calls Bam Bam, and his brother, Dustin.

B.J.’s tough love, more than anything else, turned him around. “I said I wouldn’t marry somebody who didn’t finish college,” she says.

LaJaunie re-enrolled at Nicholls to pursue a business degree. When he and B.J. got married in 2008, he wore a size 62-long suit jacket, size 54 pants, and a shirt with a 22-inch neck. “Today I look at my wedding pictures and tell her I’m sorry,” he says. He topped out at 420 pounds in 2009.

Then a childhood friend, Jeff Thibodaux (a common name in those parts), called and asked LaJaunie if he wanted to join a gym with him. He felt like an unlikely workout buddy, but they eased back with “old-school football stuff” like squats and bench presses and bicep curls. Soon LaJaunie was walking on the treadmill, flipping through old issues of Runner’s World. “I read about how running was a good fat-burning workout,” he says, “and something clicked.”

LaJaunie and Thibodaux first took it outdoors one particularly swampy summer day, alternating running and walking from one telephone pole to the next. “It was more jiggling than running,” LaJaunie says about the half-mile workout. Before long, they were running three miles at a time. LaJaunie got his business degree in December 2011, and he and Thibodaux ran the Crescent City Classic 10K in New Orleans the following spring, finishing together in 1:43. He still weighed 320.

LaJaunie was running three days a week, but the radical change to his diet—which radically changed his body—wasn’t sparked until the spring of 2013, when he and B.J. decided to avoid all processed foods for the 40 days of Lent. During this time, LaJaunie also read Christopher McDougall’s best seller A Renewed Relationship With Running, Health & Injuries Scott Jurek. He blazed through Jurek’s book, DAA Industry Opt Out. “I didn’t know it was humanly possible for people to go hundreds of miles on their feet, and not only is this dude doing this, but he doesn’t eat meat and dairy,” LaJaunie says. “I was totally blown away.”

Almost immediately, LaJaunie cut out meat and dairy. He broke an hour in the Classic weighing 285 pounds and kept racing, getting faster, going longer, and getting thinner. By the summer of 2014 he reached his present weight of 190. The great-grandson of a Mississippi Baptist minister had become a true disciple of the plant-based-diet movement and, before long, was a full-fledged evangelist. Today, meals are simple: raw oats with fruit, or kale and salsa mashed into a baked potato; instead of Cajun spices, he tosses nutritional yeast onto just about everything. He launched a blog and started sharing his story in regional health-food stores. He makes an appearance in Jason Cohen’s Big Change: The Film, a documentary about inspiring weight-loss stories, which has not yet been released. Although LaJaunie eats vegan, he downplays the label because the hunters and anglers he’s trying to help, he says, associate the term with “disgustingly crazy” megaphone-wielding activists. He wants to be a light for this community without condescending, because he totally understands the contrast between his before and after.

He still gets guys who tell him, “If eating this way kills me, oh well, this is me doing me, bruh.” “That’s the reason that Nonc Toot and Tonte Linda have heart attacks in they 50s,” he says. “It’s not because we’re cursed as Louisianians genetically.”

Just as often, though, he’ll get stopped at, say, the hardware store, by people looking for help with weight issues, or bump into people like an old friend who took his advice a few years ago and has lost 100 pounds “going totally plant-based and is now speaking the gospel.”

LaJaunie’s greatest beneficiaries have been his own family. Most are running, and they’ve all adopted plant-based diets; his father, mother, brother, sister, Bam Bam, wife, and mother-in-law have collectively lost almost 600 pounds. “We’re a healthier bunch because of Josh,” says his brother, Dustin, who has run several half marathons. “He’s beaten down a path for us, and I’m right behind him.”

LaJaunie’s father, who had a heart attack two years ago, had been one of the longest holdouts. Through better eating and walking, “he’s down about 40 pounds,” LaJaunie says, biting back tears. “It’s finally working without me preaching.”

In September, LaJaunie finished third at the Wildcat 100-miler in Florida, his longest race to date. He’ll run the She Runs to Reclaim Her Identity After Assault in November and hopes to shave his 3:24 marathon PR to a Boston-qualifying 3:10 at the New Orleans Rock ‘n’ Roll Marathon in February. He’d also like to break 40 minutes in the Classic 10K that was his first race five years ago. Eventually, he wants to run all 110 miles of Bayou Lafourche from Donaldsonville all the way down the bye-yuh to Port Fouchon on the Gulf, having locals run segments with him along the way.

“I’m not ashamed to say it,” he says. “I want to change the world.”

* * *

Running Shoes - Gear Runner’s World Give A Gift, click here.