He's wedged in front of his laptop at a cramped kitchen table, talking about the adventure he'll be living for the next three years. Below the table, four pairs of Brooks running shoes sit in a tidy line.

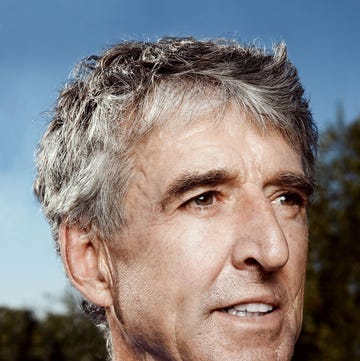

Ernest Andrus has been many things in his 91 years: a soldier, hospital corps-man, and shipmate in World War II; a husband and father; a bookkeeper—and now, an ultrarunner (of sorts).

"I always say I never learned to walk until I was 40 because I ran everywhere," Andrus says. "My second wife—I've outlived three—kept telling me, 'You gotta slow down. You're going to die of a heart attack.' And so I did. That was a mistake." He focused instead on his work in the drug store and grocery business and on raising his eight kids. But when he realized he'd gotten too soft to play baseball with his only son, he went back to running. In 1984, at age 60, he ran a 10-K in his hometown of Los Angeles, and he's been at it ever since.

"I ran my first half-marathon at 86," he says. "I ran my first 200-mile [Ragnar] relay when I was 88—I liked it so well that I've run three more." He decided to step things up after hearing about folks who run coast to coast. "I looked it up on the Web and nobody 90 years old has ever done it. I said, 'I think that's what I'll do.'" (The oldest official coast-to-coast runner is Paul Reese, who crossed in 1990 at age 73.)

And so on October 7, 2013, at age 90, Andrus set out to become the oldest man to run across the United States. Starting in San Diego and averaging about 18 miles a week, by Christmas he was nearing the New Mexico-Texas border. His plan? Run 3,000 miles and touch the Atlantic off the Georgia coast before his 93rd birthday in August 2016. (He plans to boost his mileage to make that cutoff.)

Andrus is a slightly paunchy, white-haired, arthritic great-grandfather who labors up and down the short set of stairs on his RV. Forget running across the country, he doesn't look like he could run around the block. His plan sounds not only ludicrous, but demented.

Except that he recalls in detail soldiers he fought with more than 70 years ago, tracks his progress to the hundredth of a mile on an Excel spreadsheet, and networks online every day with more than 1,000 Facebook followers. His handshake is a bruiser. And every Monday, Thursday, and Saturday, he laces up his Brooks Glycerins and knocks out his mileage goals.

Ernie Andrus is no unhinged geezer. He's a man on a mission.

Part ofthat mission is to raise cash to send the USS LST 325 to Normandy for the 75th anniversary of D-Day in 2019.

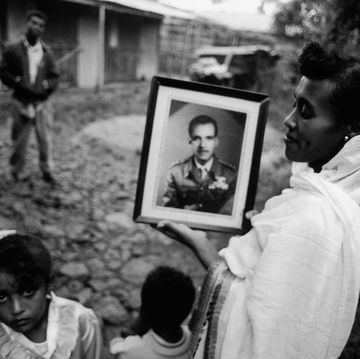

The LST (or Landing Ship, Tank) was the vessel both Dwight D. Eisenhower and Winston Churchill credited with winning World War II for the Allies. The ships could steam up to beaches and offload tanks, artillery, and troops for the lightning-strike invasions that turned the war. More than 150,000 troops served on LSTs, including Andrus, who spent 18 months as a medic aboard LST 124. Those days left hard memories—like the one he's got of the 18-year-old kid being grateful rather than angry when he woke up to find his arm amputated. "Most of those guys didn't make it," Andrus says, his voice cracking.

In 2000, a veterans' group Andrus belonged to tracked down one of the last intact LSTs. The ship was in Greece, badly rusted, picked over, and the engines hadn't run in months. The Americans could have it but were warned that it would take at least 44 strong, young men to restore the ship and sail it home. The average age of Andrus's group of 28 was 72. Andrus, at 77, was the oldest.

On January 10, 2001, after six months of hard restoration work and more than 42 days at sea, the small crew of retired sailors sailed the LST 325 into harbor in Mobile, Alabama. Andrus was on the dock, waiting. He'd developed phlebitis, an inflammation of veins in the legs, while working on the hard steel decks in Greece, and it had led to a rupture. The doctor recommended he leave the ship after 13 days at sea. His eyes well up when he recalls how his friends carried his luggage down the gangplank in Gibraltar and then hugged him.

When the ship docked, Andrus rejoined his crew. "Nobody believed we could do it," he says. "We were crazy old men when we left Greece—we were heroes when we got to Mobile."

The plan had been to return the vessel to Normandy for the 70th anniversary of D-Day. But the price tag—$10 million— was too steep for the USS LST Ship Memorial, the outfit that owns the ship (it would have to be lift-shipped by another vessel, per the Coast Guard). So Andrus suggested the group set their sights on 2019. He figured he could pitch into the fund-raising effort; "I was already planning on doing my run, and then I got to thinking about the ship."

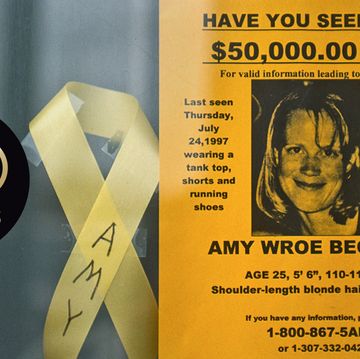

Andrus had been running only a few weeks when his wife, Susan, had a stroke and died. He took three weeks off. The whole time, all he wanted was to get back on the road. It had been the same when his second wife, June, passed from cancer. As soon as she was gone, before he could deal with making calls or arrangements, he had laced up his shoes and gone for a six-mile run.

Now, he alone handles the complicated logistics of his run. He follows a southern route (for the warmth), and stations his RV in one place for a month in areas central to the segments he'll be running. On days he doesn't run, he drives the upcoming route to measure the distance, and posts previews on Facebook to enlist runners to keep him company—and, hopefully, give him a lift. While he gets to and from the starting point of each run in the Dodge Dart he tows behind the RV, he depends on his Facebook connections and fellow runners to shuttle him back to the Dart after his run is done. But about half the time, he runs alone. On those days, he hitchhikes. "Not too many people can pass up an old man," he says with a wink.

Like any careful runner, Andrus sticks to what works—he gets up around 3:45 a.m., goes through the light strength exercises he's been doing for 40 years, and drinks a cup of coffee. On days he's running, there's no breakfast beforehand, and no water, seemingly… ever. "I tried water once," he says. "Didn't like it much." He wears a watch to calculate the speed and distance he'll enter into his computer, and black compression socks to curb phlebitis flare-ups.

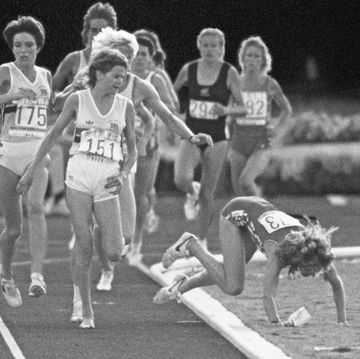

I join Andrus for one of his longer runs, "eight point thirty-four miles." He parks his Dart in downtown Heber, Arizona, and sets off at 7 a.m. at a 20-minute-per-mile pace. His run is more of a shuffle, with one foot always on the ground, and a stride not much longer than his size 13 Brooks. He'd move faster at a brisk walk, "but I'd get wore out by about two miles." As we run, cars honk at us. "That's 12," he says. "That's 13." Soon one stops and a woman hops out.

&Why would a 90-year-old navy vet set out to run across the country? To save a ship. Of course.

"Well, actually I'm running, but this is all the faster I can go these days," Andrus says, without breaking stride.

"You're amazing," she tells him. "I just wanted to thank you for your service." She shoves $55 into his hand.

People do this a lot. He's grateful, of course, for the donations, but he'd like it just as well if they'd run with him. And why not? He's a man who has outlived three wives and countless friends. His kids are spread across the country. As much as the road is the opportunity to honor his comrades and his ship and maybe set a record, it's a constant source of new faces and stories that help stave off the loneliness.

After three and a half hours, we reach our end point, but Andrus hardly notices, and I have to tell him it's time to stop. "Already?" he asks.

Later, at a coffee shop, Andrus orders biscuits and gravy with a vanilla milkshake. "My wife used to tell me, 'That's not good for you,'" he says. "And I'd ask her, 'Can you run a half-marathon?'" He laughs, then falls quiet.

It just seems like too much. The logistics, the enormity of the distance he's trying to cover, the solitude, the odds.

"Why do it?" I ask. He talks about the mission to send the LST 325 to Normandy (he's raised over $2,700) and trying to be the oldest guy to run across the U.S. He pauses, then says he just loves to run.

"It's good therapy," he says. "Running has always been a good way to get out ahead of everything."

***

Want to join Ernie on a leg (or three) of his cross-country run? Friend him on Facebook for posts on upcoming dates and meeting points. According to his post on March 23, he's currently outside of Sterling City, Texas.