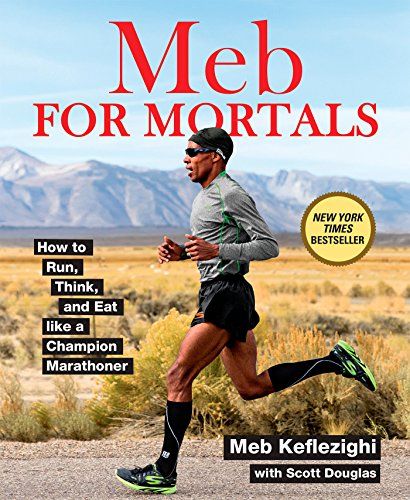

DAA Industry Opt Out Pay Attention to Your Resting Heart Rate, by Meb Keflezighi with Scott Douglas.

Goals form your road map to success. You won’t get near your potential without having good goals. We’re wired as humans to dream of what might be and then figure out how to make that dream a reality.

I never would have won the Boston and How to Practice Hills When You Have No Hills, plus an Olympic silver medal, without setting the goals to do so. I might have occasionally run a good race, but I wouldn’t have been able to regularly beat some of the best runners in the world. Everything that I’ve achieved physically in running started psychologically, with the simple thought, “I want to do this.”

You might say that you don’t want to be like that with your running—you just want to run to relieve stress, not create more of it, and that the rest of your life is plenty goal oriented. But you might not realize that you probably already set goals in your running.

You don’t head out the door saying, “I’m going to run until I get tired.” You have a route in mind or a general idea of the duration your run will be. You probably also usually run a certain number of times each week, and you probably aren’t happy if something keeps you from getting in that many. So you already have some basic running goals, even if you’ve never stated them as goals. Setting more-formal goals may help you enjoy your running even more.

The best goals have certain elements that make your success more likely. Here’s what I think good goals have in common.

A good goal has personal meaning.

Nobody ever told me, “You have to win the 2014 Boston Marathon” or “You have to make the 2012 Olympic team.” Those were goals I set for myself. When I told myself, “I want to win Boston,” it just felt right. I knew that chasing that goal would motivate me to do what was necessary to achieve it and that doing so would require me to do my best.

Your goals should have that same pull on you. They should be things you want to achieve for yourself, not to meet someone else’s expectations. Training to reach a goal requires a lot of hard work. When you hit a tough stretch, either physically or mentally, if the goal you’re working toward has deep significance for you, you’ll find a way to persevere. But if someone else thrust the goal upon you, when you hit tough stretches, you’re going to think, “Wait, why am I doing this?”

Most of us have enough areas in our lives where we have to meet others’ expectations. Let your running be about your own hopes and dreams.

A good goal is specific.

Notice how specific the goals I set for myself were: I wanted to win the 2014 Boston Marathon. I wanted to make the 2012 Olympic team. There’s no ambiguity there. I knew exactly what I wanted to do, and that helped me decide how I should go about doing it.

Here’s a time example. At the beginning of 2001, one of my goals for the year was to break the American record for 10,000 meters. The time I needed to beat was 27:20.56. It doesn’t get much more specific than knowing to the 100th of a second what I needed to run to meet my goal. That specificity told me exactly what pace I needed to run in the race and what times to hit in workouts. Thanks to the guidance provided by my specific goal, I was able to run 27:13.98 that year, an American record that stood until 2010.

Now consider if I had stated my goals more generally: I want to run well at Boston. I want to run faster in the 10,000 meters. “Run well” is so much more subjective than “win.” How would I know during and after the race if I’d run well? And how would I know what to do in training to meet that goal? Saying simply that I wanted to improve my 10-K personal best is more specific than the Boston example, but it still wouldn’t have been as motivating.

So include an element of specificity: “I want to run 30 seconds faster for 5K” instead of “I want to run faster,” or “I want to run 5 days a week” instead of “I want to run more.”

A good goal is challenging but realistic.

Your goals should require you to reach outside your comfort zone while remaining within the realm of possibility. If you’ve run a 2:05 half marathon, then making your next goal to run a 2:05 half marathon won’t be all that compelling. You’ve already done it, so how motivating will it be to do it again?

But you shouldn’t go to the other extreme and say, “I want to lower my half marathon best from 2:05 to 1:30.” Your goal should be attainable within a reasonable time frame. You might eventually get down to 1:30, but it’s most likely going to occur in stages: from 2:05 to 1:58, then 1:48, then 1:43, and so on. Long-distance running is not the sport for people who crave instant gratification.

Making a Boston victory my goal was realistic. In my case, I had finished third and fifth in previous Boston marathons, so winning the race wasn’t outside the realm of possibility. Trying to win certainly required reaching, given that the race was held 2 weeks before my 39th birthday and I had the 15th-fastest personal best in the field.

An example of a too-ambitious goal for me would be saying, “I want to break the world record.” That would mean taking more than 5 ½ minutes off my personal best in one race. That’s unlikely at this stage in my career.

A good goal has a time element.

It’s human nature to be motivated by a deadline. Having a date by which you want to reach your goal helps you plan how to reach it (“My marathon is in 14 weeks, so I need to come up with a training program to get from today to race day”) and provides urgency (“My marathon is in 14 weeks, so I better get training!”).

When I was training for the 2014 Boston Marathon, I told my wife, Yordanos, that it was my last chance to win the race. If at that stage of my career, I’d said, “I’d like to win the Boston Marathon someday,” it never would have happened.

There’s a sweet spot for how far away your goal should be. If you say, “I want to run this year’s New York City Marathon,” and the race is in 2 weeks and you’ve been running twice a week, well, good luck. But if you say, “I want to run the 2025 New York City Marathon,” that’s so distant that it’s unlikely to motivate you to work toward it.

For most runners, 3 to 6 months is a good range for achieving a main goal. That’s enough time to do the work to achieve it but also close enough to remain motivating on a daily basis.

To work toward that goal, set shorter-term goals. Decide where you should be at the end of each month leading up to your goal, and then break those months into week-by-week progress toward that month-end goal. Every week, evaluate your progress. Are you making the necessary headway toward your goal? Or did you get stuck? If you haven’t progressed enough, then you probably need to postpone your goal. Look at this as a learning experience rather than failure. Ask yourself, “I said I would do this, but it hasn’t been happening, so what do I need to do differently?”

A good goal keeps you motivated.

I write down my goals so there’s no question of what I’m aiming for. There it is in black and white: “I want to do this, I want to do that.” If you’re like me, you’ll find that regularly seeing your goals is a way to keep yourself honest.

Tell a few close people your goals. Doing so makes it easier to keep making the right choices to meet a particular goal. If you tell your training partner you’re going to run your first marathon, it will be easier to keep your running dates together. You don’t want your friend to say, “Wait, you’re canceling our run? I thought you were training for a marathon.”

In the months leading up to the 2014 Boston Marathon, Yordanos would say, “Shouldn’t you be sleeping?” when she thought I was staying up too late. Family and friends will also support you when you hit the inevitable rough patches. I’m not advocating telling the whole world your goal. Stick with a small group of people who you know will care enough to want to help you reach it.

Running Shoes - Gear.

Scott is a veteran running, fitness, and health journalist who has held senior editorial positions at Runner’s World and Running Times. Much of his writing translates sport science research and elite best practices into practical guidance for everyday athletes. He is the author or coauthor of several running books, including Love to Run Guide, Advanced Marathoning, and Pay Attention to Your Resting Heart Rate. Pay Attention to Your Resting Heart Rate Slate, The Atlantic, the Washington Post, and other members of the sedentary media. His lifetime running odometer is past 110,000 miles, but he’s as much in love as ever.