EVERY FEW SECONDS, THERE’S ANOTHER FLASH IN THE DARKNESS, and for an instant you see them—the jubilant Chinese ultramarathon runners, lit up, posing for photographs. At 5 a.m. on this day last May, roughly 200 of them are gathered in the chill that envelops Juyongguan, China, where the ancient Great Wall lures millions of tourists annually from nearby Beijing. And never mind that The North Face 100, the exasperating 62-mile race that awaits them, offers some 2,100 feet of vertical climbing. Nearly all of them are spritzing around as though they’re about to embark on a champagne cruise.

Everyone is taking digital photos of everyone else. One wizened 58-year-old racer, Bian Jinghai, is wearing an orange bandanna pirate-style and inexplicably shouting “Mao Zedong is up there, and I am down here” as he dances about like a prize-fighter poised to enter the ring. Another older runner vows to race barefoot, in homage to Mother Earth, and tiny, 92-pound Xu Yuan Shan, who claims to have once run a 2:45 marathon, is raging around Nixon-like, flashing the victory sign at myriad cameramen.

Amid this morning’s starting-line mayhem, though, one athlete, an American, is almost totally still. Diane Van Deren is standing off to the side, by the shuttered Great Wall souvenir stands, wearing sunglasses and a fresh, glistening coat of sunscreen as her husband, Scott, holds her close, quietly offering counsel.

Van Deren is 50, and she’s traveled from her Colorado home as an athlete sponsored by The North Face, the race organizer. In the days before the race, Van Deren has proven a sprightly and winning spokesperson for the outdoor apparel company. Five feet nine inches tall, and blond with blue eyes, she exudes a windblown good cheer and a certain renegade spark. She’s promoted running in near religious terms. “When I run in the mountains, that’s my medicine,” she told the Chinese journalists during a press conference. “That’s my heart.” She’s also told the story of how she once ran up 14,110- foot Pikes Peak in Colorado, and then hitched a ride down on the back of a stranger’s Harley. She’s a jaunty jock who travels nearly everywhere in pastel-bright running togs, and she’s a sentimental mother of three 20-something kids. Back in Beijing, she brought a roomful of reporters to their feet by singing, a cappella, a song she’d written herself about her son, a Marine who until recently was driving a Humvee through the battlefields of Iraq.

Now, however, Van Deren is silent. Her face is impassive behind her wraparound shades. This race—every race—looms large for her. Her running career is the culmination of a long and trying saga.

For nearly 17 years, until she was 37, Van Deren suffered from epilepsy, enduring hundreds of seizures, sometimes as often as two or three times in a week. With each seizure, she lost consciousness for about a minute. Usually, her body just went limp as she stared off into space. But there were also the two dozen or so grand mal seizures she suffered, when her muscles radically contracted and her legs and arms flailed uncontrollably. With each seizure came the distinct chance that she could die. Rather than risk death, she did the next best thing: She let doctors drill a hole into her skull.

In 1997, Van Deren underwent a partial right temporal lobectomy. Doctors removed a portion of her brain that was the focal point of her seizures. The surgery ended her epilepsy; Van Deren hasn’t seized once since the operation. But the surgeon’s work created a blind spot in the upper left part of her vision. And there is also the residual neural damage from the seizures. She cannot track time well; she is always running late, and she has almost no sense of direction. Her memory is weak—she can’t recall where, exactly, she took her honeymoon—and when she’s confronted with excessive sensory noise, as she is now, at this clamorous starting line, she gets weary and irritable. Sometimes Van Deren needs to lie down and nap for hours.

She is an ultramarathoner with extraordinary limitations. In races she must cover hundreds of miles, and yet often has no idea how long she has been running—or where she is going.

Still, Van Deren’s surgery may actually have aided her distance running. “The right side of the brain, where Diane had surgery, is involved in processing emotion,” says one of her doctors, Don Gerber, a clinical neuropsychologist at Craig Hospital in Denver. “The surgery affected the way she processes her emotional reaction to pain. I’m not saying Diane doesn’t feel pain, but pain is a complex process. You have a sensory input, and then the question is: How does the brain interpret that? Diane’s brain interprets pain differently than yours or mine does.”

Gerber’s assessment is controversial among neurologists, and all that’s certain, really, is that Van Deren has almost primordial gifts of endurance. In February 2008, in the Canadian Yukon, she won the Yukon Arctic Ultra, spending nearly eight days pulling a 50-pound supplies sled 300 miles and through temperatures that plunged to around 50 below. The next winter she covered 430 miles. And once, in Alaska, she trudged 85 miles through snow on a sprained ankle after stepping in a moose hole.

This race in China will be, relatively speaking, a cakewalk. Still, it begins by scrambling up about 1,000 steep steps carved into the Great Wall itself. “Dear runners,” says the race starter, speaking in stiff, stilted English as she summons the runners to the line. “Dear runners.”

When the race starts, the field erupts with hoots of applause. Van Deren moves forward, quietly, her head down.

Courtesy of Diane Van Deren when she was 16 months old. Otherwise healthy, she came down one day with a high fever. She was rushed to a hospital near her childhood home in Omaha, Nebraska. Nurses packed her quivering body in ice, but still she trembled for almost an hour. The seizure was not extraordinary. About five percent of American children endure a fever-induced seizure before age 5. Most never seize again. For many years, it seemed Van Deren would end up in that lucky majority.

As a kid, she played catcher on a boys’ baseball team, going by the name Dan and shoving her pigtails under her cap. As a teenager, she was a Colorado state champion in tennis and golf. She left high school early to spend four years touring the United States and Europe as a professional tennis player. She also ran a bit to keep fit. In 1982, at the age of 22 and on a whim, she entered a marathon in southwest Texas and won the women’s division.

Her infantile seizure had scarred a small portion of her right brain, though, and the cells there were vulnerable to reinjury. In her 20s, without even being aware of it, Van Deren began having tiny seizures. They didn’t manifest as convulsions, but rather as subtle perceptual shifts. Out on the tennis court, or while relaxing at home, she had what she calls “funny sensations. It was like a deja vu feeling,” she says, “like you’re in a dream, and you’re thinking, Oh, what’s happening right now has happened to me before. You feel like you’re floating; it’s an out-of-body experience.”

Lasting just seconds, these mini-seizures were “auras,” in neurological parlance. Auras are the first stage of a full-blown epileptic attack. Dr. Mark Spitz, the University of Colorado neurologist who would later order Van Deren’s surgery, describes them as an electrical phenomenon. The brain, he explains, consists of millions of cells that are “wired” to one another to transmit sensory, motor, and processing data. “When an aura occurs,” he says, “it’s like the beginning of a fire in the brain. That fire can grow so that the person is increasingly vulnerable to stronger seizures.”

None of this was evident, though, when Diane and Scott Van Deren met in 1982. The two were recent college graduates, and he was taken by her larksome spirit and drive. At the time Diane was training for the Ironman World Championship. She was a novelty—Ironwomen were still rare then—and Scott was smitten. “She seemed spontaneous,” he says. “She seemed fun.”

A DELICATE OPERATION To cure her of seizures, Diane Van Deren underwent a right temporal lobectomy. The surgery removed a golf ball-size portion of her brain (including a piece of the right temporal lobe and a piece of the hippocampus) that processes emotional content, such as memory. While no longer suffering seizures, Van Deren is plagued by short-term memory lapses. She also has difficulty processing directions, a function of the parietal lobe, which was injured by earlier seizures.

The Van Derens married when they were both 23. A few years later Scott went to work for Mountain Steel & Supply, founded by Diane’s father. Diane worked there herself, in sales, but lasted only six months—and never pursued another desk job. “Office work has never been my thing,” she says. She taught aerobics instead, and kept running, sometimes five miles, sometimes 20, a day. When the mood struck, she entered a local triathlon.

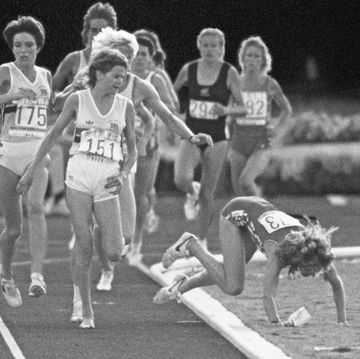

By the time Diane was 28, she was pregnant with her third child. Her brain was at the mercy of hormonal shifts. One night, as he lay in bed, sleeping, Scott awoke to the sound of his wife having a grand mal seizure. “She was violently shaking,” Scott says. “I’d never seen a [grand mal] before.” Diane had been diagnosed with epilepsy due to an attack earlier in that pregnancy, and now, Scott says, “I thought to myself, Here we go. I knew that we were entering a new chapter in our lives. I moved a lamp, so she wouldn’t knock it over, and then I called 911.”

For years afterward, Scott would lie awake in bed, intently listening. “I got very in tune with Diane’s breathing,” he says. “Snoring was a good thing; it meant she was getting some peaceful rest.” But there were more seizures, and when their children were small, says Scott, the household “revolved around how Diane was feeling. There was constant worry over when she’d have her next seizure.” Each one crushed her. “I’d feel like I’d been run over by a truck,” Diane recalls. Depending on the severity of the seizure, she’d take to bed for two or three days. Nannies were hired to drive the children and to clean the house.

Throughout all the trauma, though, Diane evolved a rare trick: She learned to abort her seizures by running.

She had noticed that her attacks usually occurred when she was resting—at the movie theater, say, or in a quiet restaurant. Her brain cells were “idle” then, as Dr. Spitz explains it, and as such more prone to “catch fire” when an abnormal seizure discharge occurred. What she needed to do was to activate brain cells quickly, the instant she felt an aura come on. Few people can do this, Spitz says, but Van Deren kept her running shoes by the door, and whenever that eerie deja vu feeling settled upon her, she stood up and rushed toward those shoes. “I knew that I only had a few seconds,” she says. “I had to get moving.”

Dr. Spitz says Van Deren’s seizures always began in her right hippocampus, a small sea horse-shaped ridge that sits deep within the brain, storing and retrieving memories. “Running,” he says, “probably activated the part of the hippocampus where seizures started. When the cells there were active, they didn’t accept the abnormal electrical activity, and the seizure fizzled out.”

She laced up her shoes and started running—out her driveway and then over ranchers’ tawny, fenced rangeland in the rural area outside of Denver. “I’d go right out into a forest,” she says. “I’d be anxious, but there was a softness to being outdoors. I felt the pine needles underfoot on the trail, and listened to the birds. It calmed me. I kept running. The point was to just keep my mind going, my body moving. I’d run until I’d broken the cycle of the seizure. Sometimes I’d run for two or three hours.”

AFTER CLIMBING UP THE GREAT WALL, THE RACE COURSE ROLLS ONTO BACK ROADS. Then, roughly 12 kilometers into the race, it climbs to its highest point, at 2,477 feet, offering a hazy view of Beijing 30 miles away. From the ridge top, it’s a steep, pounding descent into Tiger Valley, where, near the 19K mark, race officials have festooned several desolate cliffs with 20-foot-high red and white banners.

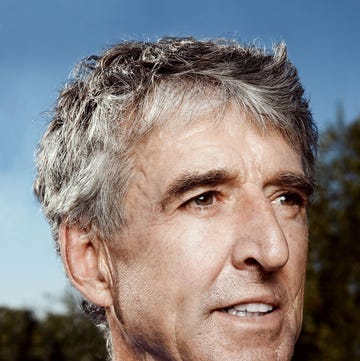

Scott Van Deren and I are standing beside these banners, on the bank of a river, in the morning coolness, waiting. Van Deren is a big man—6'4" and quite fit, thanks to a weight-room regimen and a heavy cycling habit. His voice is deep, and his manner toward his wife protective and steady. In 1995, when Diane was suffering frequent seizures, he moved the family to their current home on a 35-acre windswept property in Sedalia, Colorado, in part so that Diane could be around horses. “There’s something therapeutic about brushing horses,” he says.

Scott now owns the family steel business. He has the confident air of a man accustomed to getting things done, but at this moment he can only peer with hope up the mountain path as the runners start trickling down toward us, their voices echoing in the narrow canyon. First comes a boyish-looking Chinese student, 23-year-old Yun Yan Qiao, bounding through in one hour, 39 minutes. The first woman—43-year-old Zhang Huiji—comes through at 1:57. More than 20 minutes later, Scott Van Deren is still waiting. “I expect her any moment,” he says.

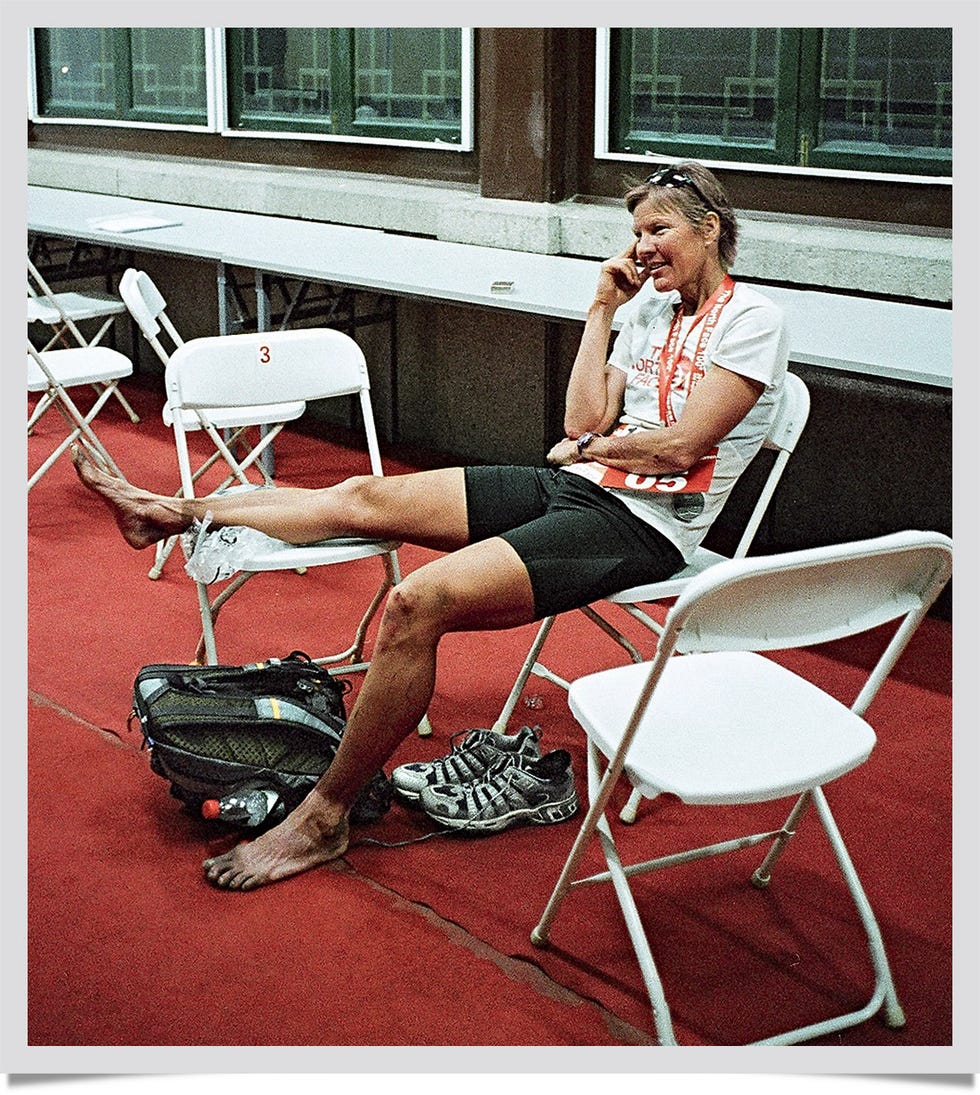

Scott has waited helplessly like this before. In 2008, at The North Face Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc, Diane started the 103-mile race with a fever and began shaking as she ran. Twice she stopped to sleep for an hour—something she’d never done before. It took her more than 40 hours to finish. Today, after two hours and 22 minutes, she finally comes through the 19K mark, in eighth place in the women’s race, running at a 12-minute, 15-second pace. She’s not far off from where she should be, really. By her standards this race is a sprint—it doesn’t play to her strengths—and at 50, she’s older than all but one woman beating her. Still, Scott is worried. “My instinct is this isn’t her day,” he says. “She looks tight.”

Indeed, Van Deren’s face is a tense mask, her stride slightly halting and choppy. She strained her Achilles a few months earlier during a predawn run. It’s been stiff ever since. But it’s impossible to discern if Van Deren’s in pain, for she’s dialed into the race. When she comes to the aid station at 26K, now in seventh place, Scott can only try to get through to her by delivering one clear message that he’s carefully rehearsed in his mind. “Get your pace,” he says. “You’ve got three big climbs ahead.”

Scott isn’t a coach. He’s never been a runner. His advice isn’t necessarily astute. It’s chivalrous. For a few seconds he runs beside Diane. “You look great, babe,” he shouts as she gulps down some water.

“I’m outta here,” says Diane. She tosses the water bottle and then breaks into a trot.

WHEN VAN DEREN FIRST BEGAN HAVING GRAND MAL SEIZURES in 1988, she refused to give in to them. Unable to drive, she walked to the supermarket, three miles away, pregnant, and pushing her two infant children in a stroller. Then she walked home, with the groceries in a backpack. Once her kids grew, she went downhill skiing—and wrapped her arms around the back of the chairlift each time she boarded, so she wouldn’t fall out if she seized.

The auras kept coming, though, and sometimes Van Deren didn’t grab her running shoes fast enough. She seized, and more cells in her brain died, and more rewired, and as a result her prelude-like auras shortened and shortened. “The seizures,” she says, “overtook my body and my confidence. I tried to dig deep and hide my confusion. I didn’t want my kids to feed off my fear.”

Nonetheless, Michael Van Deren, the Marine, says that his mom’s illness permeated his childhood. He remembers his mother once having a grand mal attack in the living room when he was 7 and his dad was away for the weekend. “It was full-blown,” says Michael, who is now 24. “She was clenching her teeth. I yelled at Robin and Matt”—his younger siblings—”to leave the room. I didn’t want them to see that.”

Scott Van Deren adds, “Diane’s epilepsy absolutely dominated the relational pattern of the family. The second I walked in from work, I’d ask, ‘How’s Mom? What’s she doing?’ I couldn’t rest.” The next seizure was always a threat. Once, when Scott was treating customers to dinner at a restaurant in Vail, Diane seized at the table. “It was a casual meeting on a summer day,” he says, “and we hadn’t discussed Diane’s epilepsy with those people.”

But the seizure that pains Diane most, in hindsight, happened when her daughter, Robin, now 22, was in grade school. Diane was coaching Robin’s basketball team, and at a game, before hundreds of spectators, Diane says, “I had this aura and the next thing I knew the other coach was standing over me, saying, ‘Diane, is everything okay?’” The gym went silent. “I was out of control,” Diane says, woefully re-creating the moment. “I couldn’t control myself, and I hurt for my children: They had to see their mom having a grand mal seizure right on the gym floor.”

Dr. Spitz wanted to send Van Deren to surgery, but he could operate only if he could identify the source of her seizures. To do so, he brought her into the hospital, deprived her of meds, and then attached electrodes to her scalp to measure electrical activity. She proceeded to have three seizures over the next four days. A videotape of one, a grand mal, shows Diane biting her tongue and then gurgling audibly on the bloody saliva in her throat.

Dr. Spitz isolated Diane’s problems to her right hippocampus. She’d be seizure-free, probably, if the damaged tissue there was excised. Spitz saw surgery as Van Deren’s safest path. Without it, her seizures were likely to become more severe and more frequent, he explained, and she faced about a 10 percent chance of dying from a seizure over the next 10 years. The surgery, in contrast, delivered just a three percent chance of a stroke. “I was calling Spitz’s office over and over, trying to get into surgery right away,” says Diane. “I was in fear of dying of a seizure.”

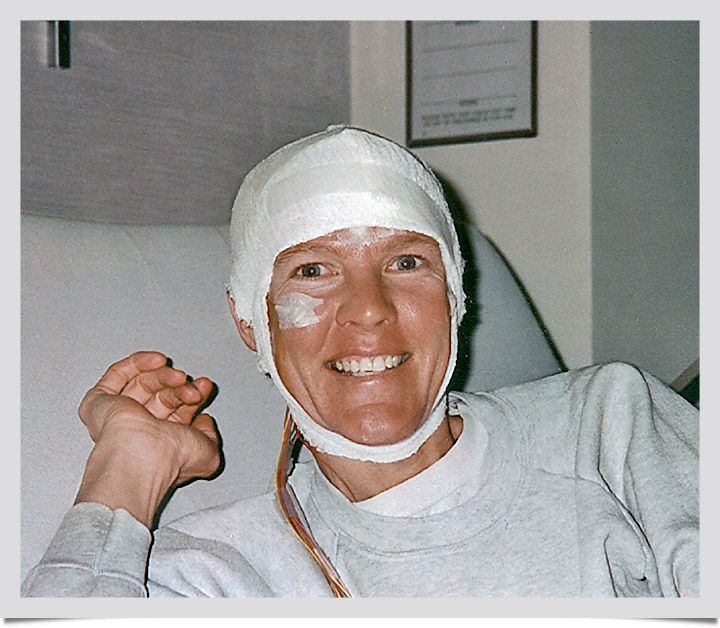

Scott was more measured. He insisted they seek a second opinion. Again, surgery was recommended. So in February 1997, in Denver, a neurological team operated on Diane’s brain. Using a high-speed drill, the surgeon removed an outer section of bone from her skull. He cut deeper, into the brain’s dura, or protective membrane, and then focused a microscope on the exposed temporal lobe. Using an aspirator, he excised part of the lobe along with the affected portion of the hippocampus.

A few hours after Van Deren awoke, she felt “horrific pain.” And it seems that her innate stubbornness kicked in. There was a shunt lodged in her skull, to drain blood, and she tried to tear it out. According to Scott, “She tried to get out of the room. A doctor and two nurses had to strap her into the bed, and she tried to bite one of them. Then she kicked a nurse.”

The doctors had to remove the partially dislodged shunt, exacerbating the pressure in Van Deren’s head. “When I went in to see her,” Scott says, “she was like a combative animal. She said, ‘Get me out of here. Why are you letting them do this to me? I hate you.’ She called me every name in the book—f---ing this, f---ing that.”

“The brain is very personal,” Diane would explain later. “It doesn’t like be messed with.”

BY THE TIME VAN DEREN REACHES THE AID STATION AT 32K, she remains in seventh place. She has blood on her arms and her shins. While running on rubbly dirt a few miles back, and staring downward in search of good footing, she couldn’t see the low branches surrounding the narrow trail due to her poor peripheral vision. A couple of times she had tripped and fallen down. But she continued to press on. “I just listen to my feet when I run,” she had told me earlier, “and I try to get a rhythm going. I breathe in two steps. I breathe out two steps.”

At one point, Scott Van Deren and I ride in a van alongside Diane. We’re so close to her that we can hear her footfalls. “Get mad,” Scott yells out the window. “Get mad now!”

“You got any gels?” Diane asks. “Got any gels?”

We don’t. There’ll be nothing for her to eat until the 44K mark. She sucks at her energy drink and keeps running.

WHAT DIANE VAN DEREN REMEMBERS MOST FROM THE WEEKS FOLLOWING THE SURGERY is the pain. “Every time I’d bend down, it hurt,” she says. “Even tying my shoes, I felt like my head was going to explode from the pressure. I played golf, and when I put the tee in, my head just throbbed.” She was eager to run again, however, and roughly a month after the operation, she did, covering 10 miles, gingerly. “I tried to hold my head as steady as possible,” she says. Still, she kept running every day. “The mountains were my safe zone. I was at peace there.”

Having worked with many patients who had undergone surgeries similar to Van Deren’s, Dr. Spitz says the weeks, months, and even years after such an operation can be as emotionally challenging as they are physically. “You need to figure out what your future in this world is without having seizures,” Spitz explains “And that can be harder than you might think. I’ve seen many divorces take place after the surgery. In the years before her surgery, Diane had pretty much stopped competing because of the seizures. She had become very dependent on her family. Now she had to figure out what to do with her new life.”

For a while, Van Deren seemed content to live in the moment. When she ran, her husband says, it wasn’t about competing; it was about “being free and outside.” Van Deren could cover 20 miles on the trails, and when she was done feel invigorated versus being exhausted. And then she would run a little farther.

Finally, in 2002, roughly five years after her surgery, she entered a low-key race—a 50-mile Colorado trail run in which there was only one other entrant. “The race director had to run along with them through the first few miles,” Scott says, “to show them the route.” Diane finished, in a tie with the other runner, and soon she was dreaming big. Later that year she signed up for The Hardrock 100, which climbs more than 30,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies. “If I could get through years of seizures and then brain surgery,” she says, “I could take this baby on. I could do it.”

Hardrock’s race director stifled Van Deren’s race plan, though—she needed to have previously finished at least one 100-mile ultra. Undeterred, she jumped into another 100-miler, this one starting in Leadville, Colorado, elevation 12,600 feet. She ran for about 70 miles, twisted her knee, and continued to hobble on. When Van Deren finally dropped out at the 72-mile mark, her desire to run, and to compete, had only intensified.

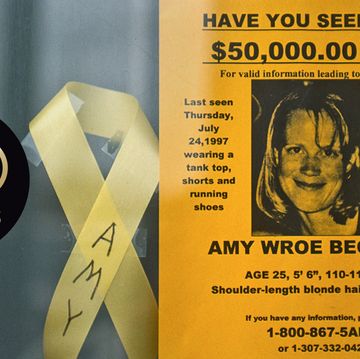

She began planning for her next 100-mile race, and, Van Deren told a friend, Kathy Pidcock, “I expect to win it.” Pidcock, who was then an elite ultrarunner, crafted for Van Deren a rugged training program—a 100-mile-per-week regimen heavy on high-altitude training and back-to-back 25-mile outings. “Whatever I told her to do, she did,” says Pidcock. “She never questioned me, and she was so strong. I knew she would make it.” She did. In June 2003, Van Deren completed the Bighorn Trail 100 Mile Run, in Wyoming, in 31 hours, 54 minutes, finishing sixth in the women’s race. She figured, “I’ve done it. That’s my last one.”

Two days later, though, she talked to a roomful of gradeschoolers with epilepsy at a camp in Colorado. “These were kids who had 20 or 30 seizures a day,” she says. “They were having seizures right in front of me, and one of them, a girl named Mandy, asked, ‘Are you going to run another 100-mile race?’”

Van Deren’s feet were still swollen; her shins were bruised from postholing in snowfields. But Mandy persisted: “Will you run your next 100-miler for me? I can’t run. I have seizures.”

“I felt guilty,” Van Deren says. “I thought, If I could only give them a piece of what I’ve felt overcoming my epilepsy…”

Soon, Van Deren was the first woman finisher in the San Diego 100-Mile Endurance Run, placing second overall. Then in 2004, over a six-month period, she ran seven ultras, including three longer than 95 miles. In 2004, after finally being accepted into the race, she was the ninth-place woman at the Hardrock 100.

How did Van Deren rise so suddenly from obscurity? Granted, she’d already proven herself a world-class athlete, but that was in tennis, a very different sport. And she’d run some, sure. But what enabled her to knock off so many ultras, so speedily, with so little recovery time? Each year, thousands of Americans have epilepsy surgery. Can we expect some of them to start flourishing in endurance sports with new and magical pain-tolerance?

Dr. Gerber credits her endurance in part to her brain limitations. He says runners who can better track time and map where they are can be distracted by the details. But Van Deren has a special facility for what he calls “flow” that lets her transcend the anguish of running long. “It’s a mental state,” Gerber says. “You become enmeshed in what you’re doing. It’s almost Zen. She can run for hours and not know how long she’s been going.”

But Dr. William Theodore, chief of the clinical epilepsy division at the National Institute of Health, says no evidence exists that epilepsy surgery will cause a change in pain tolerance. “Certain parts of the brain are related to pain, but they’re very deep structures. They’re almost never involved in epilepsy surgery.”

Another expert, Dr. Jerome Engel, director of the UCLA Seizure Disorder Center, says the majority of epilepsy patients who undergo partial lobectomies do not experience either diminished brain function or changes in character. Still, Engel calls Van Deren an “atypical case.” While he has never examined her, he’s struck by reports of her unusual postsurgical cognitive problems— of her trouble with getting lost, for instance. To him, such symptoms suggest that her brain bears “bilateral damage;” in other words, her presurgical seizures could have scarred both lobes of her brain. If that is the case, Engel suggests, “it could affect her pain tolerance.” He explains that the electrical shocks involved in a seizure cause the brain to release its own opioids, or pain relievers. When both sides of the brain have endured seizures, the opioids’ effect is, Engel says, “more powerful.”

One medical professional who worked directly with Van Deren thinks the equation is simpler. “Diane was a great athlete before surgery, and she’s still a great athlete,” says Mark Spitz, her original doctor. “The surgery didn’t change that.”

Van Deren herself disagrees, slightly. “The surgery helped,” she says, “because it was painful. I learned how to endure pain. But I’ve always been superfocused and stubborn.” Van Deren argues that her gift lies in keeping up the fight—in refusing to wallow in sadness, even amid the trials of epilepsy and her current impairments. During a recent 50-mile race, she says, “A guy knocked me off the trail in the first mile. I rolled my ankle all the way over and just kept running, for 49 miles more, even though a PT thought it was broken. Here’s why I’m good: I don’t give up.”

Best Running Shoes 2025, and the course markers are nowhere to be seen. Several runners get lost, and our guide—Sky Song, a young North Face marketing rep—gets a call: The top 10 runners are stalled at a country store. We begin flying toward them. En route, we see diminutive Xu Yuan Shan, the 2:45 marathoner, churning along, just off the lead pack. “Get in the van,” Sky cries out the window. “You’re lost!”

Xu climbs in, sweaty and winded, and then Song keeps rolling. The leaders elude him, though. Some, but not all, catch a ride back to the course from a policeman, and soon there’s another snafu. When leader Yun Yan Qiao hits the 50K aid station, he looks for the drop bag he packed the night before with extra socks and snacks. Race organizers were supposed to bring each runner’s bag to this station, but Yun’s isn’t here. In exasperation, he drops out. Later, when Van Deren learns that Yun quit, she’s disgusted. “He could have finished,” she hisses. “So many people in ultras lose it when one thing crumbles. You just can’t do that.”

Van Deren doesn’t. In 2008, in the Yukon Arctic Ultra, her water bottles froze solid—for 20 miles, she ran without a drop. A few days later, she reached the Yukon River in 70-mile-per-hour winds and didn’t know which way to go. As the wind tossed her to her knees, she began marking her way with red tape. She went in one direction for an hour. When it appeared that was the wrong way, she doubled back, patiently. She kept at it for four hours and eventually found her way.

Now, in China, Van Deren’s caught in another long struggle. All day, there’s been a phenom running ahead of her—a chipper young Chinese woman in navy knee-length pants, a red collared shirt, and cheap gray running sneakers. Zheng Rufang, 28, is primarily a cyclist. She trains with the Chinese national team, and she’s dressed, she’ll say later, to signal, “I am not a runner. I know nothing about running.” About 75 kilometers into the race, her inexperience starts to show. Climbing a small mountain, up hundreds of concrete steps, past little Buddhist shrines carved into the cliffs of the Yinshan Pagoda Forest, she’s worn out—dragging. There’s another Chinese woman just ahead of her. And when Van Deren chugs up behind them, out of sight but closing, it’s as though she can smell the roadkill.

“How far ahead are they?” she asks as she passes me on the stairs. Her cool reserve is gone now, more than 11 hours into the race. Her face is sunburned, and there’s an edge of wild hunger to her voice.

“About three minutes,” I say.

CA Notice at Collection.

FOR ALL HER AMBITION, DIANE VAN DEREN CAN SEEM VERY VULNERABLE. On a trip to Beijing in 2009, she got lost for two hours after leaving her hotel for a run. It was the sort of misadventure that could befall any tourist, but the incident still looms for Van Deren as terrifying: worrisome proof of her limitations. She remembers being on the verge of tears and desperately beseeching directions, in shouted English, from the white-gloved soldiers who stand on small pedestals all over Beijing, stock still, at attention. The Chinese businessman who eventually saved her, leading her by the hand for more than a mile, back to her hotel, still shines for her as a saint.

Van Deren’s general disorientation could prove fatal in competition—what if she took a wrong turn in the Arctic?—but she insists that it is also an anguishing impediment at home, in day-to-day life. She forgets appointments, she says, and cannot remember people’s faces. Once at a family gathering, when everyone was asked to name their favorite Christmas, she drew a blank. “So many emotions were packed into those 10 seconds,” she says, “Sadness, frustration, embarrassment. You don’t know how much pain these disabilities have brought me. It’s challenged my relationships with my family and friends.”

Donald Gerber, the neuropsychologist, has provided her counsel over the past six years. He meets informally with Van Deren before each of her races. He tries to anticipate the trouble she might encounter, given her brain injury, and then devises coping strategies. “You want to minimize distraction and dangers,” he says, “and make everything as routine as possible.”

It was Dr. Gerber who advised Van Deren to take red tape to the Arctic, so she could mark her path if she got lost. Before she ran the snowy course of Alaska’s Iditarod on foot, he likewise advised her to stop if suddenly the snow underfoot seemed soft and untrammeled by dogs. “That could be a sign you’re off the Iditarod Trail,” he advised.

As Dr. Gerber himself admits, his tips are “not rocket science.” But they give Van Deren a certain assurance. “When I go out to race,” she says, “I feel confident. And that’s because Don and I had put together a game plan. I’m prepared. I’m always prepared.”

You got any gels? Diane asks. Got any gels, and on up to where the mountain is just a windswept exposed rock looking out onto a succession of other slabs of basalt speckled with small, green, scrubby trees. Then she guts past Zheng Rufang and the other Chinese woman. At the 90K checkpoint, she’s intent on burying them. “That girl in red,” she shouts to Scott, “she’s on my ass.”

Scott Van Deren is now riding in Sky Song’s van. “Babe, she isn’t on your ass,” he shouts out the window, a bit wearily. It’s been a long day for him, too, and in fact, neither Chinese woman is anywhere in sight now. They’re fading.

“She’s on my ass. Where is that girl? Is she walking behind me?”

Genially, Scott ignores the question. “You look good, honey,” he says. The van revs away from Diane, and then, with a smirk, he says to me, “Sometimes you have to lie.”

The course rolls onto a mostly flat paved road, and between 90K and 98K, Van Deren passes 14 men. At about the 99K mark, in the darkness, Scott is anxious again as we sit in the idling van, by a fork in the road. “Wait here,” he says to Sky Song. “She could miss this turn.” She doesn’t. Scott guides her in and she finishes in 13:16, good for fifth among 10 women.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back. Diane is in the back, with her feet up, resting her Achilles, which bears a swollen, grape-sized bulge. It’s dark out. She’s taken her sunglasses off, and it’s as though all her armor has melted. She’s woozy and mushy—happily delirious, like a society dowager high on martinis. “Sky,” she calls out to our guide, “you’ve been so sweet. Let me buy you a glass of wine. Sky, come to Colorado. Bring your wife.”

Scott fixes a jacket into a pillow for Diane. She moans a little, in pain. They are middleaged warriors, both of them, and Diane, who hopes to write a memoir some day, has admitted she may be nearing the end. “When I finished the 430-miler in the Yukon,” she told me, “I thought, There’s a great chapter for my book. There comes a time and a place where the odds just get slimmer and slimmer.”

The van swoops over hills, and through little villages. Eventually, we’re on the outskirts of Beijing, rolling through traffic for a few minutes before cutting north, back to our hotel by the Wall. It’s a warm Saturday night. People are out taking strolls and drinking at sidewalk tables outside cafes. Inside the van, there’s tranquility: the deep satisfaction that comes after a long race.

At this stage in her life, Diane Van Deren says her days are happy, mostly. She is grateful for her surgery—“without it,” she says, “I’d probably be dead.” And her older son, Michael, has returned safely from Iraq and begun working at the family steel business. He calls his mother before races, wishing her well. “There’s laughter in our house now,” Diane says, “and there wasn’t before.”

Weeks after we return from China, though, I give her a call. During our conversation I ask what she remembers of her trip and of the 100K race, and for a second there’s a weird silence. “I’m sitting here panicking a little,” she says. “My heart’s pounding. It’s almost like I’m drawing a blank. I remember the big picture. I remember landing at the airport. I remember being on the Great Wall, and I can always remember things that are traumatic, like falling on the trail. But other things?” There’s a long pause.

We soon hang up, and when we speak a couple of days later, she says, “You know, when I went running today, I was like, ‘Okay, Diane, think. What do you really remember of China?’” She goes on to recite her memories. They are essentially the same memories she’s already told me about, and soon she seems to recognize that once again a small part of her has been lost, irretrievably. For maybe half a second, there’s a blue silence.

But then Van Deren muscles past it, and back into good cheer. “Hey, you know, I just went to the doctor’s yesterday,” she says, “and I got an MRI done on my Achilles. There’s nothing wrong with it. It’s just tender and swollen. I can keep training, which is good. The Hard Rock 100 is only four weeks away. Four weeks, baby. It’s coming right up. I’m there.”

Story Update · July 7, 2016

In 2012, Van Deren completed North Carolina’s 1,000-mile Mountain to Sea Trail in a course-record 22 days, five hours, and three minutes. Now 56, she continues to compete for The North Face, and in June, she ran The North Face 100 (km) in South Korea, finishing 22nd in a field of 52 (men and women). Van Deren typically races every other month—“usually 50-, 60-, or 70-milers,” she says—and often gives motivational talks at race expos. She and her husband, Scott, have moved to the Colorado Springs area, where she logs 70- to 90-mile weeks on the local trails. “My health is excellent,” Van Deren says. “I don’t see doctors for my brain injury, and I pretty much know what I need to do to deal with it.” She does, however, continue to struggle with her visual memory, which can pose problems during a race. “If I start looking around or stop paying attention to the trail it can set me way off course,” she says. “I try to stay very present.” And while Van Deren may run the trails a bit slower these days, she is still competitive. “I love what I do,” she says. “I’ve competed at a high level for 16 years and remained injury-free. I focus on what I can do, not what I can’t do. I’m leading a very grateful life.” Writer Bill Donahue thinks relentless ambition has always been a part of Van Deren. “She has this deep drive and determination and, in running, found a raison d’être,” he says. Van Deren’s next race is a 50-miler in Ontario’s Blue Mountains. —Nick Weldon