China’s most anticipated 2018 spring trail race began with techno jazzercising. It was 5 in the morning, and the starting line felt like a night club. Runners gathered behind a traditional Chinese gate—the same ones that adorn Chinatowns in American cities—doing jumping jacks and toe touches, syncing their stretches to thumping bass music. An instructor covered in spandex led the calisthenics, shouting through a headset. Smoke machines exploded in rhythm with the music, and floodlights lit up a banner hung from the gate: Gaoligong by UTMB.

Near where I stood, a Chinese runner nodded in approval. “Not bad at all, the vibe here.”

EDM thumped for the next half hour, until Li Zhaohui, the event’s emcee and broadcaster at the the Beijing Olympics’ track and field events, took the stage. That morning, he donned a vintage American Air Force flight jacket, embroidered with the emblem of A Renewed Relationship With Running, the U.S. squadron that fought alongside the Chinese in this region, just north of the Myanmar border in Yunnan Province, during World War II. Strapped around his forehead were retro, 1940s flight goggles. The crowd cheered his entrance.

“We are here…in Tengchong, the most beautiful city!” he proclaimed, first in Chinese, then in heavily accented English.

“You can conquer the mountain…of Gaoligong! You can fly. You…can touch the sky…like an eagle! You are all heroes! It is…amazing!” The runners and crowd cheered, more than 200 strong.

Next to me was Pavel Toropov of Xingzhi Exploring, the Chinese company organizing Gaoligong alongside UTMB, the top ultra race in the world, in France. The spectacle didn’t faze him. He’d been organizing races all over the world since 2011—a seven-year career of “industrial running” as he called it—and Gaoligong was his latest project. Once, he told me, he’d set a course in a Sri Lankan jungle while trying to avoid getting trampled by elephants. In Tengchong, he stood behind the gate calmly, expressionless, glancing occasionally at the foreign athletes he’d invited to the race. The morning’s 55K start marked the first of three races that weekend, with a 125K and 160K to follow. Ultrarunners Sunmaya Budha and Meredith Edwards were heavy foreign favorites in the women’s 55K, Jason Schlarb and Nathan Montague in the men’s.

On stage, Li Zhaohui continued to rhapsodize, building to a crescendo before presenting the elite athletes, one by one, to blasts from smoke machines. Schlarb, Edwards, Budha, and Montague jogged onto the stage, and crowds of recreational runners pushed toward the guard rails, holding up their iPhones for pictures. Li Zhaohui again praised the racers as a collection of heroes, and the clock began its countdown to the 55K.

The elite racers exploded out of the gate to surging music, and, behind them, crowds of recreational runners followed, with bright jackets and hydration packs, cheering and snapping pictures. Toropov called me over to a car, and I hopped into the backseat. Richard Bull, a race organizer in Nepal who had brought Nepalese runner Sunmaya Budha to the race, climbed in with me along with James Poole, a British runner and Hoka ambassador documenting the event for Strava. As we passed the runners on the road, heading into the mountains outside Tengchong, Poole looked up from his iPhone.

“Well, that was quite something, wasn’t it?” he said. “Reminded me of those improv theatre games: Give me a sporting event! Ultrarunning. DAA Industry Opt Out! China. Best Running Shoes 2025! Dance party.”

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below.

In the last five or so years, events like Gaoligong have embodied the glitzier side of a massive Chinese running boom. Most Chinese race organizers mark the surge as having begun around 2011 with a deluge of marathons, followed by a second wave of trail-running events in 2015. In those early years, many races were organized haphazardly, with frequent disasters. At some events, volunteers wouldn’t show up because of bad weather, aid stations would be missing, and medevacs weren’t available. Since then, Pavel told me, race quality has dramatically increased. That’s partly because of experience, but also because of the movement's organic, grassroots oversight of races on social media. When I spoke with Shen Bo, a cofounder of Gudong, the closest Chinese equivalent to Strava, he estimated that China now had at least 200 million runners.

“Are you sure?” I asked, incredulous. “That’s one of every seven people.”

“Mass participation in sport has skyrocketed these last few years in China,” he said simply.

That was the highest estimate I heard by far (others, like race organizers from Sanfo, the Chinese equivalent of REI, guessed about 20 million). Yu Lanjiang, the founder of Zuiku, China’s most widely used race registration app, said there were more than 800 road races that he knew of in 2017, along with at least 450 trail traces. This year, he expects the total to climb to more than 1,500. Sanfo put the number even higher, at more than 2,000. There were rumblings about China trying to get on the Ultra Trail World Tour, and this past April 15th, more than 40 marathons were held on the same weekend.

“That’s the weekend Chinese officials see as having the best weather,” one runner explained to me. “Plus, they’ve heard that the Boston Marathon is that weekend, too, and that’s the famous one everyone knows!”

When I first lived in Beijing, back in 2006, a Chinese running frenzy was hard to imagine. Jogging on the street drew stares, and most runners stuck to tracks. Historically, running was something to avoid once you could afford to—a form of manual labor for peasants that a new middle class wished to avoid. Or it was a Marxist vestage. In the 1950s, Mao encouraged mass participation in sports to develop a kind of nationalist, proletariat strength, but little was ever said about the sport’s more individualist utilities.

But in the late aughts, a few years after I arrived, norms began shifting. A spiritual void was growing—for community, meaning, individual goals, and new pastimes—left by China’s abandonment of Maoist communism, which capitalism couldn’t always fill. “When Mao died in 1976, belief in communism began to erode. Now, four decades on, his successors have found the absence of a belief system to be a problem,” The Economist wrote last year. “Shorn of Dao and Mao, modern China has been left with a corrupt party state and a brutal, Wild West capitalism. In a recent poll 88 percent of people said they believed that there was a moral decay and a lack of trust in society. This is part of a much bigger crisis of identity.”

At first, Chinese began running because of its accessibility, as more middle class began exploring new recreations. But soon after, many stumbled onto the more social, communal aspects that filled those bigger holes—the identity and support that comes from belonging to a larger running tribe. “Chinese people began to ask, ‘Now what?’” one race organizer told me, discussing the mood after the 2008 Olympics, when China achieved its nationalist fantasy of winning the gold medal count. In the Games’ aftermath, athletics became less centered around global bragging rights and more introspective, more individually focused. Chinese were setting goals for themselves, organizers told me, running for their own mental health, and less for abstract notions of national strength.

As I dove deeper into the Chinese running phenomenon, I kept coming back to those social shifts, which often contradicted the popular image of Chinese authoritarianism. Running was becoming a ubiquitous middle-class hobby, and a more individual notion of sport was taking hold in the lives of both elite runners and hobbyists, leaving the older paradigms of sport—its more nationalist ethos and the dominance of state institutions—behind.

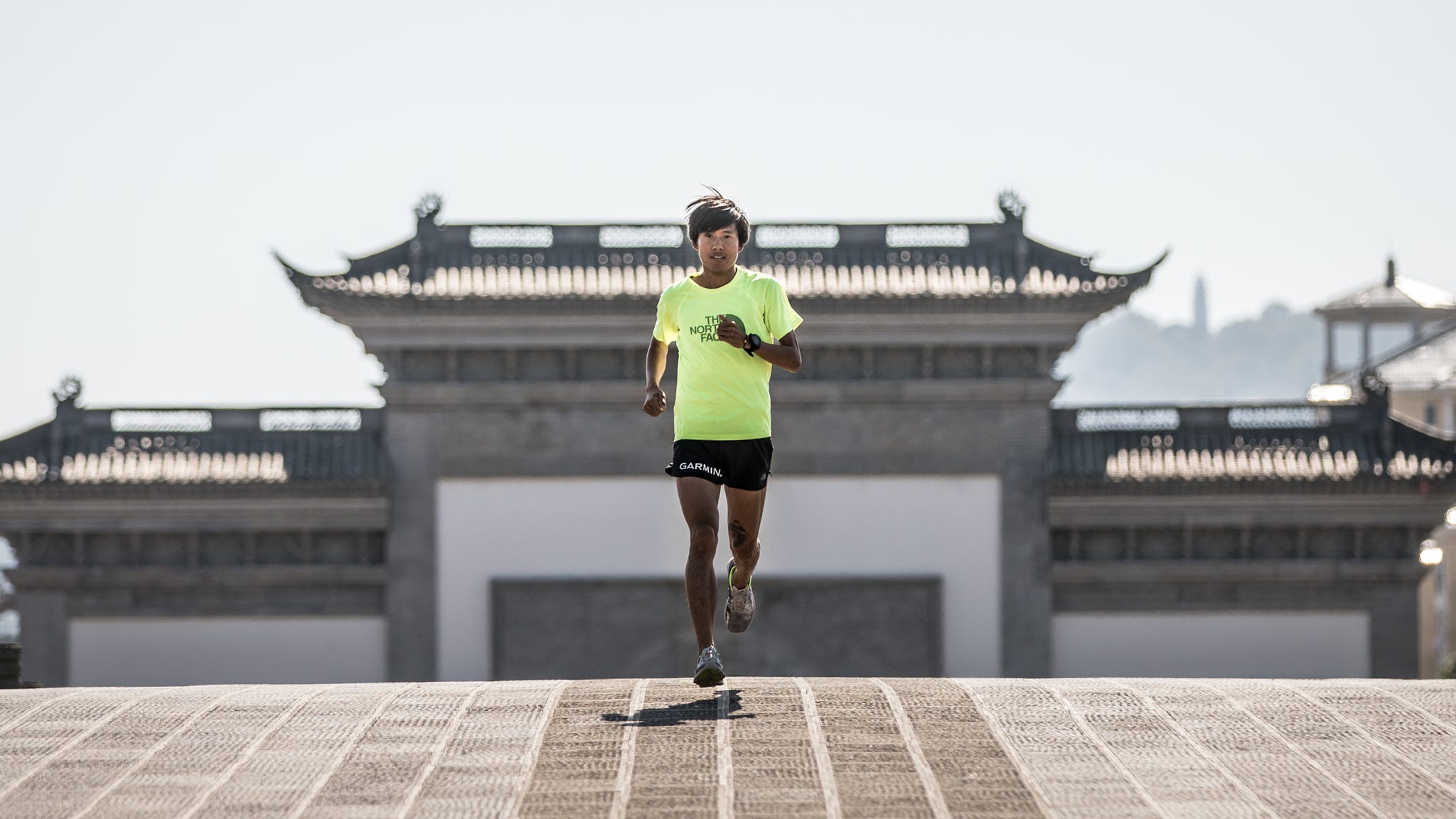

One of China’s best runners, Garmin-sponsored Qi Min, recently left that old baggage behind. He’d grown up in a poor region of rural Yunnan, at more than 5,500 feet in elevation, about a 10-hour drive from urban Tengchong. When he was 11, he dominated a middle school track meet, and coaches from the local county’s sports academy came calling. The next year, his family enrolled him at the government-run county academy, the lowest rung in the Soviet-inspired system.

He attended school in the mornings and trained in the afternoons—a significantly reduced workload compared to regular schools. While he missed his family terribly, Qi Min showed promise as a runner. By 14, he’d ascended to the provincial team. Athletes spent their entire time training there, three hours in the morning and three after lunch, and no longer took classes. Nobody was allowed off campus, and nontraining hours were used for recovery, until lights out at 9 p.m. At competitions, he was exposed only to hotels and competition zones. A shuttle bus drove them between.

“We’re completely cut off from the outside world,” Qi Min told me, speaking in Chinese and laughing dryly. “It’s kind of like criminals living in jail, where you have no idea what’s going on outside, except for what you can see on your electronic devices. I never liked it, but you can’t leave, since you’ve got no way to survive outside the school. I have a high school diploma from the sports academy, but it doesn’t mean anything.”

Qi Min compared the academy to military training, and echoed a common criticism of China’s sports system—the incredible cost of sacrificing an education for athletics. He referenced Olympics hopefuls who, with little to no education, had gone broke after their athletic careers ended.

When he was 26, Qi Min forced his way out by faking a knee injury. It was only then he began to enjoy running, competing in established trail races in China. Soon, he’d attracted commercial sponsors like Garmin, whose blue pullover he wore the entire weekend at Gaoligong. Now, at age 29, commercial running has transformed his life, as well as the lives of some of China’s other top runners—though not without risks. Leaving the state system means forfeiting an “iron rice bowl” of subsidized housing, wages, and medical care guaranteed by the government—an increasingly rare set of state welfare benefits in China still made available to select government employees, including athletes during their careers.

Still, the last year had been good to Qi Min. A few weeks before Gaoligong, he and his girlfriend, Yao Miao, also an elite ultrarunner, turned heads by winning the Vibram Hong Kong 100’s men’s and women’s divisions. After the race, Qi Min remarked that he hoped one day to join the ranks of the world’s greatest trail runners, challenging some of the best American and European pros.

Not everyone responded to Qi Min and Yao Miao’s wins with grace, however. Toropov told me that Qi Min’s comment brought about some pooh-poohing from western runners, a holier-than-thou attitude the Brit resented. In many sports, there’s a tendency for western audiences to view Chinese athletes as faceless, robot-like figures without personalities, with the exception of big name stars like pro basketball player Yao Ming or retired tennis star Li Na. In the more extreme displays of condescension, Chinese athletes are criticized for fudging their age, or taking performance-enhancing drugs. After Yao Miao and Qi Min’s wins at the Hong Kong 100, message board comments cast doubt on the results. “Was there any PED testing?” one asked. “This is a very relevant question, especially applicable to any athlete that was part of a government system,” another commenter named Very Concerned responded. It’s a perception that betrays a harmless ignorance at best, a colonial superiority and even racism at worst. Toropov, once enrolled in a Soviet Union academy himself before moving to the U.K., admired runners like Qi Min. After the system they’d survived, he believed, their success shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone.

It was hard to imagine a more dramatic change in lifestyle than the one Qi Min had undergone. He and Yao Miao now lived in Dali, one of China’s most beautiful cities and a base for adventure tourism, on the edge of the Tibetan plateau in Yunnan. He was roommates with his best friend and training partner, Shen Jiasheng, another escapee from the state academies and a favorite for the 125K race at Gaoligong. The two of them frequently posted photos on WeChat—a Chinese social media platform that combines Facebook-like aspects with text messaging—of their running adventures in the mountains. The posts were popular, selling running as a carefree lifestyle. The two were rooming together at Gaoligong, as they did at many races.

I enjoyed watching Qi Min interact with fans in the days leading up to the race, stationed beneath Garmin’s tent at the Gaoligong start. He was patient with the endless requests for pictures, and many of his admirers were running in the race. Athletes who went through China’s state training academies tended to be shy; Shen Jiasheng, for one, spoke in a more reserved tone, but Qi Min cracked sarcastic jokes and smiled widely for photos. When I asked him whether all the attention, especially from girls, ever annoyed him, he almost interrupted me.

“Not at all,” he said. “Of course I love it!”

Naturally outgoing, Qi Min wanted to branch out even more. In the fall he was hoping to study English, which he never learned in the training academies, to interact with more foreign athletes and outgrow what he admitted had been a poor education. Toropov noted that Qi Min always avoided speaking in his local Yunnan dialect, even when around friends like Shen Jiasheng—a sort of pledge to himself to avoid sounding less-educated. There were practical reasons, too, of course, for learning English: At one race in Hong Kong, he’d taken a wrong turn after misreading a sign in English, costing him an extra 12 kilometers.

When I asked him whether he’d like to see the sports system changed in China, he gave a devious grin.

“Well, you know, in China, you shouldn’t run your mouth too much,” he said. “But I hope it becomes a more open system eventually. I just hope that you won’t have kids forced to do things they don’t want to do.” What he admired most about the top athletes in trail running around the world was that they were mostly obsessed hobbyists. In China, passion wasn’t a required prerequisite for the development of a promising athlete. One day, he hoped it would be.

When I spoke with Shen Jiasheng, a few days later, he agreed. He’d been out of the system for more than a year now, but he was already frequently posting pictures of his free-range life in Dali.

On WeChat, Qi Min and Shen Jiasheng were making up for time lost to the academies and provincial teams. They posted playful photos of themselves showing off their abs, alongside photos and jokes about their training runs in Dali. “Training on your own, without the provincial teams’ coaches, you might not be as fast,” Shen Jiasheng told me that weekend over tea, “but it’s a better life.” He’d saved a picture on his iPhone with a quote from Kilian Jornet on running, written over a scenic mountain background: If you don’t have pleasure when you train, you will never improve. “I like that quote,” he said. “I think he’s probably right.”

In one of their skits for WeChat, which Shen Jiasheng posted from a street in Tengchong, Qi Min walked by a runner crouching on the ground like a beggar, and then dropped some spare change into his hat.

“Doing a good deed every day” they named the video.

I showed the clip to Toropov, who burst out laughing. The context of the video was hard to miss. In China, there was an infamous story of an athlete with Olympic dreams who had been found begging on the street following retirement. And most runners like Qi Min and Shen Jiasheng were still in tenuous financial situations, which they often dealt with through dark humor.

The Best Songs to Add to Your Playlist this Month.

“Fun, right?” he said.

Wei Jun, a former bureaucrat who left the sports ministry in 2014 to found his own race outfit, was more cautious in declaring sponsored athletes who’d escaped the state system as having “made it.” The pressure to over-compete for prize money and attention, he told me, was an incentive many newly commercial runners in China struggled to handle. Qi Min, Yao Miao, and Shen Jiasheng trained without coaches, who tended to work only at the training academies, and that could mean a higher chance of getting injured.

On WeChat, when I asked Qi Min why he didn’t hire a coach, he gave a simpler, half-joking answer, which he sent to me with two frowning emojis.

“Because I’m the coach.”

In his next message, he elaborated. “I’m Team Yao Miao’s coach + boyfriend.” Then he added a smiley face.

At Gaoligong, another Chinese runner, Li Yungui, was out in front at the 55K’s first 10K checkpoint. A few minutes later Schlarb, Budha, and Montague followed. Bull was elated, cheering on Budha, adding playful heckles now and then to the crowds of runners bringing up the rear. After more than a year of coordination with UTMB and Chinese authorities, Toropov was thrilled.

The first checkpoint stood on a grassy hilltop of brown fields manned by a local villager, Duan Shibiao, who wore a suit of camo. He’d brought a small tent up the night before, and had been staking out the spot ever since. His post was simple—a yellow stand marking a fork between the different races. He’d worked the test race of Gaoligong the year before, and he’d heard about this year’s race two months prior. Local officials had briefed the entire village on the event, and asked for volunteers.

“Last year, there was a 70-year-old who ran this race! I admire that,” he told me, when I asked why he volunteered.

The cultural and economic shifts that have led middle class urbanites to run recreationally still haven’t arrived in the countryside, which is drastically underdeveloped compared to China’s cities. In remote areas of China, the competitions are still a spectacle of awe. One runner I met named Li Zhaoyang, who had grown up in rural Yunnan and later moved to the sprawling provincial capital—as many young Chinese born in the countryside do—rarely bothered to explain to her mother who still lived back home why she ran.

“Sometimes the villagers ask you who’s paying you to do this,” another runner told me, “and then you have to explain that, actually, you’re paying someone else NYC Marathoner Ran Home After Chemo.”

Along the course, volunteers from local villages mixed in with young city-dwellers flown in from around the country, a rare blending of the two. The villagers had been provided with blue tents, and they all mentioned the briefings government officials and race organizers gave them. For Tengchong, many said this was the biggest event of the year. Downtown, there were signs everywhere, and anyone who spoke to me usually asked whether I was running.

Children occasionally joined the runners, and villagers lined the streets at the larger checkpoints. In Yongle, one of the bigger villages along the route, locals stopped traffic and watched closely, many of the women hoisting infants on their backs as the runners sped by.

“My first reaction to the race was that I didn’t believe it,” a local from Yongle named Ren Changchen told me. “It’s incomprehensible, that kind of distance!”

After a few hours of touring the checkpoints, we arrived at the finish, in Heshun, a preserved old town of stone alleyways just outside Tengchong. The top runners of the 55K began to finish, with Li Yungui taking first place, and Jason Schlarb finishing some 20 minutes later. Budha finished fifth overall, for a dominant win in the women’s field.

Later that afternoon, Shen Jiasheng cruised past the finish line, taking first place in the 125K, which began the same morning. Thunderous applause and iPhone snaps from the crowd greeted him, while the gregarious emcee Li Zhaohui nearly gave himself a heart attack showering praise. Shen Jiasheng waited patiently for the second-place finisher, the young Japanese runner Ruy Ueda, who the crowd was affectionately calling “young fresh meat,” and embraced him upon his finish. A few hours later, Qi Min took off at 8 pm for the 100-miler, alongside Krissy Moehl, Mike Wardian, and Gediminas Grinius, to pumping EDM and the screams of the tireless Li Zhaohui, now dressed in a costume depicting an ancient Daoist monk. Bull and Toropov sped off to track Samantha Chan, a promising young runner from Hong Kong, and I turned in for the night. Just before dozing off, I checked Qi Min’s progress. He was winning.

I awoke the next day to news that Qi Min had dropped out at around 82 kilometers, just over halfway through the race. Toropov thought he probably had forgotten to drink enough water, a mistake he’d observed Qi Min make before, but with fewer consequences during 100K races. On WeChat, Qi Min left a message for his supporters, with an image of him clapping in thanks before the race:

“On my first hundred-miler I had to pull out of the race, overestimated myself and underestimated 100 miles…I think I still need another two years.”

Later that afternoon, I visited Qi Min and Shen Jiasheng in their hotel. They were half asleep in their beds, and Qi Min gave a polite hello. His first experience running all night had left him unexpectedly dizzy, and he’d peed blood before he’d decided to withdraw. He was disappointed, yet still in good spirits. I couldn’t help but think back to Wei Jun’s warnings about the temptations of over-racing and training. Qi Min and Shen Jiasheng told me to keep in touch. (Months later, Qi Min bounced back, crushing the pace and finishing second at the prestigious Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc’s 101K in Chamonix. Yao Miao would finish 11th A Pro Athlete Takes on The Great World Race.)

Back at the Gaoligong race finish, Gediminas cruised in for the 160K win, and Krissy Moehl came in a few hours later to take the women’s title. The next day, the podium finishers received medals, gave interviews, and made molds of their feet in yellow putty to take home. Li Zhaohui continued to monologue from the finish line. At one point, he embarked on a tangent about China’s Hundred Years of Shame at the hands of foreign powers, beginning with the first Opium War in 1839, and ending with Japanese occupation in World War II. Such running events, he implored, would surely make China a stronger nation. But the appeal to nationalism felt somewhat at odds with the actual runners, who, when I spoke with many of them, had more personal reasons for running.

“It’s just something I started doing for fun with friends,” a 50-year-old finisher, who had only begun running three years earlier, told me.

The next morning, all indications pointed to a successful event. At the hotel, Toropov was scrolling through the photos racers had shared on social media. Responses from the nearly 3,000 runners were positive overall. Li Zhaohui had lost his voice.

From Runners World for New Balance Beijing the following day, hoping to track down running groups in the city where the boom began, and talk with more organizers about the explosion of races. I couldn’t imagine how they could be commercially sustainable, nor as lavish as Gaoligong, and I wondered about a bubble. In recent years, China had had plenty of them—from stock market drops to bike-share graveyards to the overbuilding of apartment complexes.

Wei Jun confirmed my suspicions. He saw cultural ticks fueling the boom, particularly when it came to China’s penchant for copycatting and rushing headlong into a nascent market. In his office in Beijing, he pointed to the iPhone sitting on his desk. “In China, as soon as people see a friend buying something, they want it, too,” he explained. “The officials are like that when they see a rival county holding a race now. They want to have one as well. And then an entrepreneur sees all these race organizers forming, and they want to try, too!”

In China, grassroots fads and government embrace often snowball on top of one another, and running appeared to be on the same path. Races play into the political incentives of local Chinese officials, whom the governing party rotates around the country in two-year shifts. For cadres up for promotion, the best CVs highlight rapid economic growth, along with other miscellaneous accomplishments in producing civic events and “cultural services” with large mass participation. Hosting races checks almost every box for resume building. Media coverage of the races provides exposure for their city, however remote or unremarkable, and luring sponsors and TV coverage gives officials a chance to showcase alleged economic growth. And since they’re required to spend all the money they’re allocated for such events annually, there’s no incentive to hold back, nor consider—since they’ll be gone in two years—what activities might generate long-term growth. Asking whether such investments make economic sense misses the point; for Chinese officials, it’s not really about commercial viability.

Such a system, however, isn’t lucrative. “You ask anyone and they’ll tell you,” Toropov told me, “no one is making money from races in China.” Yu Lanjiang agreed. He assumed the number of runners in China would grow for a few more years but wasn’t sure about the sustainability of the commercial growth around them. Wei Jun still believed the only way to make money was to win a contract, but even making money after that was hard; hosting races required a lot of legwork in China, where going through the approval process from local authorities is much more involved than in the United States.

“It’s not like in the U.S., where a bunch of friends will just say, ‘Hey, let’s get a few volunteers together and have a race this weekend,’” one of Sanfo’s race organizers, who went to grad school in Arizona, told me. In China, expenses tend to add up quickly. In 10 years, Wei Jun expected only about 10 percent of race organizers to still be around. When I asked if a bubble burst meant there would be fewer races—and perhaps fewer runners—he hesitated.

“Maybe, but not that much less,” he said. “You know China, it’s big—they’ll just be a new wave of companies to come in and replace them. And then they’ll go bankrupt a few years later. Then new ones will come in. It’s a cycle.” Holes in the bubble would pop only so briefly before being plugged by someone else.

Zuiku’s own office spoke to those challenges. It was cramped with 11 employees. But next door there was another startup, which was building shower stations for runners in Beijing’s Olympic Forest Park, the city’s most popular place to log miles. Yu Lanjiang thought they were probably making money.

“How about Zuiku?” I asked founder Yu Lanjiang.

“Still not making money. Hopefully we’re close, though,” he said, shaking his head.

The way the race organizers spoke of China’s running boom shared nearly every defining eccentricity of China’s modern economy, political system, and cultural ticks. There was that odd combination of an enormous emerging market—the huge supply of runners—with its commercial derivatives, along with government intervention for political purposes.

And there were the foreigners, staring at the growth from abroad, slightly confused and intrigued. In Tengchong, I’d watched Catherine and Michel Poletti, UTMB’s cofounders, reacting to the hubbub. Catherine appeared calmly nonplussed, while Michel frequently nodded along to the techno in befuddled amusement. When I sat down with them for tea, I asked Catherine why UTMB had chosen China for its first branded race abroad. UTMB, she told me, had never seen the number of runners from a single country increase so rapidly.

For the elite foreign runners invited to the race, it was hard not to fall in love with the scene. The enthusiasm of China’s new runners, the pomp, the frequent absurdities, and the energy were infectious. The potential for building a brand in a country with millions of new runners was plain to see as well.

Krissy Moehl, whose training book Running Your First Ultra was published in Chinese two years ago, recalled the questions she received from Chinese runners at Q+A sessions in 2015. “People were so hungry for information,” Moehl told me. “Talking to a couple hundred people at each presentation, this new insurgence—they were just all about it.” Moehl thought that, since those talks, China had achieved the same progression in three years that the U.S. had in a decade—increased interest in training and gear, and more heated competition.

NYC Marathoner Ran Home After Chemo week, I got my own taste of the enthusiasm. On WeChat, Xingzhi Exploring invited all Beijing runners who’d participated in the event to a reunion—“A Sharing Meeting.” On a Sunday morning at 9 a.m., I showed up to watch.

The meet-up was held at a swanky event-hosting office run by Xingzhi Exploring, at the north end of Beijing’s Olympic Park. About 25 runners from the Gaoligong event attended, most of them wearing their official finishers’ jackets. For the next three hours, more than half of the group shared their race recap on stage—runners, along with volunteers and organizers—while audience members scanned their smartphones until it was their turn to share. Some of the sharers had PowerPoint presentations. A few of them cried, and another drew metaphors from famous Chinese epics on The Three Kingdoms period. Perhaps Li Zhaohui’s antics should have prepared me. I’d lived in China for long enough that such hyperbole rarely phased me anymore, but the sharing meeting produced more histrionics than I’d expected. In retrospect, I shouldn’t have been surprised; running’s grass roots craze was perfectly suited for the social-media-sharing obsession in China, which feels even more extreme than in the U.S. these days. The meeting was simply a live version. Afterward, I spoke with a race organizer I’d met in Tengchong.

“Sharing Meetings are a big new trend these days for running races,” he explained, laughing at my bewilderment. “That’s just the way society is now.”

Three days after the reunion, I met up with the Youji Running Group, named after an upstart running apparel company with a small outlet near the Central Business District. On warm days, as many as 60 runners show up to the shop. Thousands of similar groups meet around the city. Like most runners I’d met in China, they were largely urban professionals, and few had been running for more than five years. The leader of the Youji group explained his decision to start running a few years prior by showing me an older photo of himself with a pot belly. He was ripped now. “I just decided that a person probably shouldn’t turn into a ball,” he told me.

We set out jogging west, toward Tiananmen Square and a loop around the Forbidden City’s moat, a common jogging route in Beijing. We passed the first hotel I’d ever stayed at in China, more than a decade prior, where I remember watching crowds of bicycles during rush hour. There were fewer now, replaced by mopeds and cars. It was a consequential time to be running by Tiananmen Square and the Great Hall of the People: During the annual legislative session last March, China’s president, Xi Jinping, had amended the constitution to rid the presidency of term limits. Security vehicles lined the streets, but no one in the group said much about them—such sights had become commonplace in Beijing over the past few years. I couldn’t help but ponder the contradictions between the rapid growth of running—a sport that, at its essence, epitomized individualism—and the government’s more recent authoritarian turns. But China was always full of such contradictions. Its society—especially the young, urban contingent—was often moving one way, with a government moving another, and I sometimes wondered whether such contradictions would ever fully resolve themselves.

As we passed the eastern side of Zhongnanhai, the main residence for China’s central leadership, my running partner urged me to keep up the pace. “We can’t stop here,” he said, nodding toward the police officers.

We ignored them and kept going, as many tend to in China. The contradiction, I was reminded, wasn’t worth obsessing over, the way it so often was in Western media. And I thought of the real changes that seemed to outweigh the presence of an old guard: Qi Min had made a new life for himself without state support, Youji was growing its numbers, Zuiku was registering more racers, and urbanites continued to run themselves out of the shape of a ball. Running had become so big, so contagious, that no matter the maneuverings inside Zhongnanhai, or how many police lined the streets outside, China would run on.