I tie on my shoes every morning. Socks on first, toes pressed into the arch and then inched into the toe box. My heel finds itself at home in the back of my shoe, not through guidance but out of routine, and we are out the door for a run.

I am grateful that my feet don’t fight against me the way my mind does. The last month has been a constant tug of war between numbing myself to the reality of another black person being killed for no discernible reason and letting it become all-consuming.

It feels like we’ve all become experts on crisis. Adjusting to our new reality, we are stretching our imaginations and getting creative with how we work, eat, live, and communicate during the age of the coronavirus.

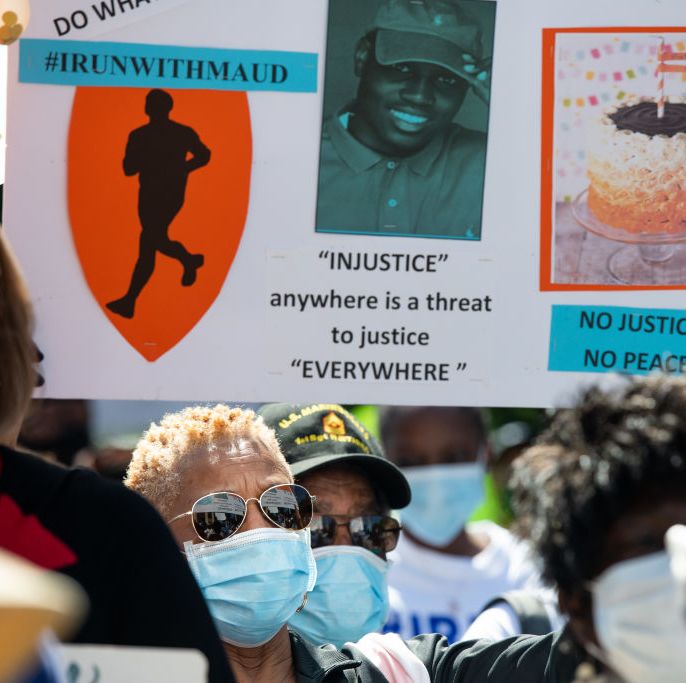

But how does one begin to understand an epidemic of violence aimed at victims like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Sean Reed? Before them, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice? And the story that has hit closest to home, Ahmaud Arbery? When police found his body, he was lying in the middle of the street, which was exactly where he was confronted, shot, and killed three months ago by Gregory and Travis McMichael for jogging.

I watched the video of Ahmaud being hunted and gunned down in Georgia, and I immediately regretted visiting the footage.

In running I find there is purposeful pain. I have learned to stretch the limits of discomfort to unlock my potential. Weekly two-hour long runs, grueling tempo sessions on the track, and intense speedwork will teach your body how to make sense of deep physical discomfort. I know pain. But watching that video was one of the most horrific, violent, and painful things I’ve ever seen.

His murder took place in February and is only being revisited through our justice system and on social platforms because of video evidence. The same is true of George Floyd. The dehumanization of black and brown bodies seems to matter only when we are forced to look at these types of graphic episodes.

The limited scope of where, and how black people can exist, can have deadly consequences. It’s often that individuals don’t recognize black people out of place from where they expect to see us. Ahmaud, who, just as many Americans are now doing in the face of COVID-19, turned to running as a way to move through uncertainty. His crime? Occupying space his killers felt was not his within which to exist.

The misinterpretation and characterization of black people’s experiences is something I know well. When I was in high school, a parent approached my coach to inquire whether my mom was white. She had seen my dad at meets to confirm he is black, but the woman was searching for something to explain my “discipline and focus.” In her world, blackness didn’t equate to those characteristics, and it certainly didn’t add up to running cross country.

People frequently ask me why I, a distance runner, went to college at the University of Texas. I had the pedigree in high school to go to a powerhouse distance program, but I chose Texas. What was my reasoning behind attending a sprint specialty school as a distance runner?

I was looking for an opportunity to be in a more diverse and more inclusive environment. I was at an age, and time in my life, where I was seeking growth, and you do that by having a variety of people and experiences you are exposed to.

I didn’t want to deal any longer with microaggressions of well-meaning friends reminding me that classmates were only asking me out not because I was desirable, but because they were curious about what a “black girl would be like” or teachers looking to me to give the “black perspective” on Huckleberry Finn. When I went to visit Texas, I saw the possibility of having a black roommate, a black female head coach, and a community where it wouldn’t be a struggle to maintain a sense of self and identity, because I saw myself reflected in my peers.

I felt angry with myself that day for pressing play on the video showing Ahmaud Arbery’s murder. I knew before I opened that browser that his killers didn’t really see him on that February afternoon. Just like that parent who asked if my mom was white never really saw me during my race. Sustained, preconceived notions of people distort authentic narratives. The human experience is vast, and racism cuts our stories short.

I keep hearing COVID-19 referred to as the great equalizer. There is this idea that we are all experiencing tragedy together, that this vortex our lives have suddenly been encapsulated in has funneled out inequalities.

But when I see Ahmaud’s mother on TV grieving her son, or when I read the staggering data of how COVID-19 has disproportionately affected black communities because of underlying health issues as a manifestation of genetics or poverty, I come to realize there are parts of this country that will never open back up to some Americans—because they were never open to them to begin with.

Here is my reality: I’m going running tomorrow. I’m not afraid to go running, but it feels inconceivable that I even have to think about it. It’s even more frightening that there will be people who don’t run tomorrow. Who will tell their kids not to run tomorrow, or whose families will sit at home wondering if their loved ones will return home.

It’s time to acknowledge that the running community, which has long been heralded as one of the most accessible, most inclusive communities, does not exclude itself from the impact that issues of intolerance and bigotry create in this country.

As a professional runner, I make a living being singularly focused. I spend months at a time sequestered in the mountains at altitude training camps in order to be performance-ready. These deaths like Ahmaud’s, however, shock the system.

They bring us back from our individual realities and demand a collective response. I find it difficult to look at these tragedies as isolated incidents. You cannot overlook the structural breakdowns in our society that allow for a young man to be murdered in broad daylight, individuals instigating police action on innocent people, harassment in parks, targeted social distance stops, and leadership that calls exhausted and enraged protesters “thugs” because they are trying to navigate and stand up against police brutality after years of justice being demanded and denied. Moving forward means truly lamenting.

But expressing grief is hard when you are navigating two realities. I often feel compelled to maintain a certain demeanor as to not alienate myself. If I talk about what’s going on, I can’t be too angry. I don’t want to offend anyone, or be overbearing with my opinions. I am on high alert to be disappointed, and above all discouraged, that human lives are being minimized to hashtags. It is frightening to see all the names and deaths that have been recorded, and even more unsettling to know that there are many more that have gone on unreported.

I’m sad, I’m righteously angry, and to be honest, I’m exhausted. Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sean Reed, and now George Floyd weigh heavily in my mind. Every day we are waking up to headlines that remind us of how fragile and undervalued black lives seem to be.

I hear people laughing about the inconveniences of having socially distant parties, and it feels forced to join in that laughter. All around me, I hear small talk about whether the lockdown was worthwhile, and guilt consumes me for taking part in those conversations.

Running Charities to Support This Year, How to Create a Running Safety Plan.

These patterns are appearing all over the U.S., yet this tragedy is often mocked or said to be blown out of proportion because of our refusal to really see and acknowledge the people it affects most.

Perceiving my body as a target for violence or fearing for my life during exercise may not be my exact experience. I do know, however, what it’s like to be viewed, but not really seen. To view Ahmaud was to see him as a criminal running away from something, because that’s what black bodies do. To see him is to know that among many things, he was a son, a student, an athlete, and a friend.

His name is Ahmaud Arbery, his murder was no mistake, and he should be alive today. His execution could send a message that black Americans can’t exercise, even when that exact action could help combat structural inequalities black Americans endure—living in food deserts and parts of the country with poor air quality, or lacking health insurance.

Ahmaud’s story is not a singular event. If we want our running community to be a force for change, and not a reflection of the biases that our nation endures, we have to be willing to consistently have a sustained conversation that will effect change and is capable of asking questions without immediate answers or solutions.

I don’t know how you unlearn the type of hate that threatens black life. I do know that the work needs to happen everywhere, not just in individual communities in Georgia, Minneapolis, New York, or Louisville.

The ripple effects of racism that lead to the violence we are witnessing are likely to be appearing in our schools, workplaces, and communities. Who is in our running groups? Who do we follow on Instagram? What books are we reading, shows are we watching, or podcasts are we listening to? Do they feature stories with people of color? I believe challenging ourselves to have relationships and interactions that are diverse, transparent, and open to authentic dialogue can effect meaningful change.

Fighting racial injustice in America is an endurance sport. It is going to take time, and sustained focus, to galvanize our communities. Being tired is not enough. The race can be won, but it requires dutiful action from all of us.

Marielle Hall is training to make her second Olympic team in 2021. She belongs to the Bowerman Track Club and lives and writes in Portland, Oregon.