Distance running with an upper-body amputation is a war against instability. Muscles can strain so much to compensate for the missing limb that they contort your spine, misalign your shoulders, and worsen your imbalance. In 2017, Ashley Jones—then 15 years old—faced a punishing return to high school sports following the amputation of her right arm. On the soccer field, she had collisions so violent that the pain would bring her to the brink of blackout. Later, during cross-country runs, the jostling of the amputation site intensified her phantom pain—which she’d already rated 7 out of 10 on normal days—to as high as 10.

But Ashley couldn’t slow down. In 2019, she competed in her first-ever cross-country season for one of the top programs in the nation—Valor Christian High School’s varsity team under Coach Greg Coplen. Ashley was green, but Coplen had been trying to recruit her for years. His passion is turning brand-new but talented runners into scholarship athletes, and Ashley had what it took. She was a fighter, Coplen says, and not just because of everything she’d been through over the previous few years. Coplen had seen her overcome physical pain that brought her to tears. He’d seen her hang with able-bodied athletes who many might think “she had no business being in a race with.” He’d seen Ashley endure things on and off the track he still can’t comprehend.

Coplen has always believed that speed emerges from efficiency and economy of movement, when a runner’s arms and legs work in tandem to generate power. He’s always told his athletes, “the arms make the runner, while the legs are transportation.” Ashley was the exception.

The Bible promises suffering—Ashley’s Christian upbringing taught her that—but throughout most of her childhood, she and her family were lucky. Ashley lived in a four-bedroom home in Santa Clarita, CA, with her twin sister, Sydney, her brothers, Quinton and Landon, and her mom and dad, Michelle and Damian. The house was an hour and a half from the Pacific Ocean, 10 minutes from Six Flags Magic Mountain, and five seconds from their swimming pool in the backyard. During the hot SoCal summers, the kids took to the water, and when Damian was home from his travel-heavy government relations job, he’d join them by the pool, cranking Garth Brooks, lighting the barbecue, and tossing them into the deep end.

Those days were gifts from God, the Joneses say, tangible blessings from a loving Lord and Creator. The family prayed together every day and read the Bible together. They went to church on Sundays. Ashley’s faith taught her that a loving, personal relationship with God is possible, and that when she experiences pain and suffering—a certainty in a world broken by sin—God is still present and in control. Ashley learned how Jesus, the son of God, willingly endured pain and suffering as he was dying on the cross. According to Scripture, God doesn’t just heal our pain; he understands it.

In 2012, the Joneses moved to Castle Rock, Colorado. Sports were a central joy for the family. In sixth grade, Ashley and Sydney joined the Storm soccer club, with Ashley playing striker/midfielder and Sydney goalie.

The team would run suicide drills, starting at one end of the field and doing sprint repeats to different yard lines; Ashley was one of the fastest runners. She loved all sprinting and running drills because she was comfortable doing them. Both girls could dominate on the field, but speed was Ashley’s gift.

“I knew it was one of my strengths,” she says. “I could get to a ball, put pressure on a girl. Wherever the team needed me, I’d be there.”

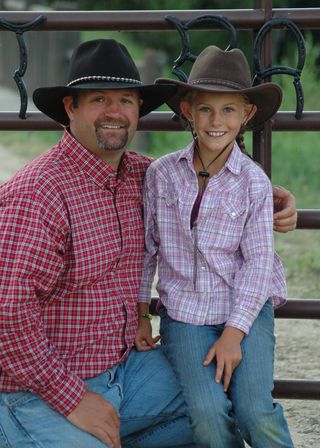

Damian was an active cheerleader when it came to all his kids’ athletic endeavors. He had a signature whistle he’d let out during their games, and afterward he’d wrap his kids in a great bear hug, come win or loss. “My dad was the best dad a daughter could ask for,” Ashley says. “He was strong. He was caring. You never talk to someone who had a bad experience with him.”

On March 3, 2016, Damian took Sydney to soccer practice, and while his daughter worked out with the team, Damian jogged the surrounding track. He was making some diet and exercise changes to try a healthier lifestyle amid all his work travel. But then, mid-run, Damian stopped. He felt a pain in his chest. It was the first sign of a heart attack.

At 14, Sydney was too young to drive, so Damian took the wheel himself en route to the emergency room. They were a quarter mile from the hospital when he started slipping in and out of consciousness. His head slammed into the steering wheel, his foot hit the gas pedal, and the truck turned and flipped. Sydney walked away unscathed, but Damian died before the medics arrived. He was 46. Michelle was the first person notified of his passing. She told Ashley and her brothers.

Ashley remembers lying in her parents’ bed that night, weeping, praying, and sleeping in fits. Above the bed was a picture of her parents. Ashley remembers staring at it and thinking, I can’t believe he’s actually gone. How are we going to move on? She says she didn’t blame God for her dad’s death. “There was a lot of sadness, but we never felt anger. We knew my dad was whole again, that he wasn’t hurting. I had the hope that I’d see him again, in heaven.” For Christians, heaven is where the faithful go to be in total unity with God. That means people in heaven are unbroken by sin, perfect.

In the weeks that followed, the Joneses gave one another space to feel everything that comes with intense, sudden loss. They sat on the couch, cried when they had to, laughed when they wanted to, and listened to a constant rotation of worship songs. Spring turned to summer, and on June 2, 2016, some family friends invited the Joneses to a weekend in Grand County, Colorado, outside Steamboat Springs, for some hiking and off-roading. The Joneses agreed. Ashley says, “It was like, let’s try to breathe again. Let’s try to live.”

For two days, the vacation was a picture of idyllic cabin life—s’mores, campfires, and boundless green space for the kids to roam. Ashley says, “I felt happy. It was weird—should I be laughing again? Should I be happy?” For the first time since Damian’s death she thought, Oh my gosh, I’m actually living again.

The teenagers commandeered ATVs and dirt bikes to explore the fire roads that wound through the hills surrounding their cabin. One road snaked to the top of a nearby peak before making a sharp roundabout and descending back toward the cabin.

Ashley was in the passenger seat of the ATV while someone else drove. She remembers thinking, as they entered the roundabout where the road ended, that they were going too fast. As the ATV took the turn, it began to fall toward Ashley’s side. She felt the wheels tilt. She knew they were going to crash and her instincts took over. She stuck her right arm out to brace herself, and the bar between the ATV’s front and back seats slammed down on top of it. Quinton, on a dirt bike nearby, saw the crash and ran over. He lifted the ATV off his sister.

Ashley’s arm was a mangled mess of broken bones and flesh. When she tried to lift it, she says, “it was like dragging something dead across the gravel.” The arm was still attached to her shoulder by some skin and her brachial artery. She lifted it with her opposite hand and held it against her chest. It bled down her clothes and onto the ground. She remembers her little brother Landon, there on the scene, begging her not to die.

While the others stayed with Ashley, Quinton and a friend rode dirt bikes down the mountain to find Michelle and seek medical help. Ashley sat on the ground, blood pouring from the wound. She didn’t think she could wait until help arrived. She had to start walking toward the adults, a trek of about a half mile. Again, Ashley prayed: God, you have to do something or I won’t get down this mountain. God, I need you. I need you to stop the bleeding.

As Ashley walked with the group down the mountain, she held her arm to her chest. She says that as she prayed, the bleeding slowed to a stop. She says God was close to her: “I had felt his presence in different magnitudes. As a powerful force, like the wind; as a sensation that someone you love is near.”

After about 20 minutes, Michelle and another parent reached Ashley in a vehicle. Michelle gave Ashley a shirt, Ashley wrapped it around her arm, and they rode down to the base of the mountain to wait for medical help. “Every bump down the road was excruciating,” says Ashley, “but I thought, I don’t want to leave my family. I don’t want them to experience more loss.”

A Flight for Life helicopter airlifted Ashley to Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora. Doctors amputated her arm that night. After the surgery, Michelle sat by her daughter’s bedside, stroking her hair, singing, and keeping a constant prayer.

When Ashley woke, she felt the place where her right arm used to be. Her mother was still by her side, and Ashley remembers asking her, “Why are these things happening to us? There has to be a reason.” Ashley reiterated to her mom that she would be okay, and when her siblings came in, she told them the same thing. She didn’t want them to be afraid.

Ashley asked God for a glimpse of his plan for her life: God, this happened for a reason, and I’m trusting you to show me what’s next.

Her recovery would be arduous—an inferno of phantom pain, daily oxycodone for a year, and coping with the loss of countless two-handed capabilities: fixing her own hair, riding a bike, cutting food with a fork and knife. Ashley says her time in the hospital—losing her arm just three months after losing her father—was rock bottom. “An amputation is one of the most traumatic things a body can go through,” she says. “Losing a loved one has similar effects. I was totally wrecked.” She took her pain to God, praying, Don’t leave me, God. I need you. I need you to lead me.

It would take months for Ashley to regain a sense of normalcy, wean herself off the oxycodone, and figure out how to live as a person with one arm. But she says there was never a day when she felt depressed or suicidal, abandoned or alone. She says God was still with her.

The book of Hebrews, Chapter 11, says faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see. For Christians, part of faith is the belief that God is going to redeem pain and suffering for good.

A week after her amputation, Ashley received a call from Bethany Hamilton, a surfer and fellow Christian who’d lost her arm to a shark attack at age 13. Hamilton invited Ashley to a retreat she’d started for girls with amputations called Beautifully Flawed, which teaches them to adapt to their new life after trauma. The promise of participating in Beautifully Flawed—and seeing how Hamilton had adapted with one arm—filled Ashley with hope.

After eight days in the hospital, Ashley went home. Just three weeks later, the Joneses went to Florida for a vacation that Michelle had planned before Ashley’s accident.

Michelle says the time in Florida was transformational for how the family viewed Ashley post-surgery. “She’s on the beach in her bikini, and she doesn’t care. She’s like, ‘This is me now,’” Michelle says. From that point on, as Ashley took ownership of her new life, the Joneses would follow her lead.

One aspect of this was Ashley’s return to organized sports. Though her first year after the amputation was crammed with physical and occupational therapy, she had planned to play for Valor Christian High School’s soccer team the following season, her freshman year. To that point, it was still her best sport.

A challenge for any amputee is dealing with the imbalance of having one limb where the body expects a pair. In the case of a missing arm, this imbalance not only twists spines and seizes muscles as they attempt to adapt, but it also destabilizes the body’s sense of control. As a result, contact sports become much more dangerous. On the soccer field, Ashley’s new lack of balance became a constant threat, and the summer before she was meant to play again for Valor High, she suffered a non-contact injury making a cut down the field. She dislocated her left knee, tore her meniscus, and tore her ACL. Another surgery. Another long recovery.

Ashley’s only alternative was to adapt. She rehabbed her knee for a year and, in August 2018, found a camp for adaptive athletes, including amputees, that focused on triathlon sports—swimming, cycling, and running. “It opened doors to sports other than soccer,” says Michelle. Ashley started training for competitions. In spring 2019, she joined the Valor High track team as a junior.

In a span of just three years, Valor High head coach Greg Coplen had transformed the school’s cross-country and distance-running programs from afterthoughts to contenders in Colorado, a state known for elite amateur programs. Coplen was the head cross-country coach, the distance/middle-distance coach on the track team, and Valor High’s campus chaplain. He had known Ashley and the Joneses for several years; he spoke and sang at Damian’s memorial and had visited Ashley in the hospital after her accident. He’d seen her compete as an athlete, and her leadership on and off the field was “very obvious,” he says. “She was just one of those kids everyone wants to be around, that all the teachers like, who’s incredibly mature and unselfish for her age.” In fact, he’d tried to persuade Ashley and Sydney to run cross-country before, but they’d always been more focused on soccer. When Ashley returned from the 2019 USA Paratriathlon National Championships in July (where she placed second in her classification), though, she was ready to make running her focus.

Ashley was already fit from triathlon training when she began running track at Valor, but she says her first few weeks of pure running were a shock. This used to be a team where anyone who joined was almost guaranteed a varsity spot, but under Coplen, Ashley was pushed into a pool of elite-level runners. “I had to start running as fast as I could [during practice] just so I could be there for them,” she says.

Distance running with an upper-body imbalance presents unique challenges. As Ashley adjusted to the sport, her hips ached from the uneven strain on her back muscles. She could relax her left shoulder when she felt herself tightening up, but she couldn’t do the same with her right. (Our arms act as natural stretching mechanisms.) The jostling of running worsened her phantom pain too. Coplen says sometimes he saw the physical pain bring Ashley to tears.

“Being a runner myself, I’ve felt a lot of the pains all runners do, but I can’t understand what she’s feeling,” he says. “Sometimes you [wonder]: ‘What kind of runner would she be if she had two arms?’ But I’m not sure she’d be as good, or at least any better than she is now. The events in her life drive her to that place of excellence.”

The phantom pain might last the rest of Ashley’s life. It has been unrelenting in the face of analgesics, narcotics, and even experimental natural remedies. It fluctuates depending on the weather, the altitude, or whether someone accidentally bumps the amputation site. Ashley doesn’t take painkillers. “I have a very high pain tolerance,” she says. “It’s a blessing and a curse.”

She ran in her first track season, in 2019, as a junior. Coplen put her middle of the pack—“because I’d only ever run about 30 minutes consecutively,” she says. Almost immediately she outperformed everyone’s expectations, helping the Valor girls win the 4x800-meter relay at the Colorado State Championships. Then it was on to cross-country in September as a senior. Ashley says from the beginning of her cross-country career, her own endurance surprised her. It was a sign of things to come.

In December 2019, the Nike Cross-Country National meet invited 201 women and 22 teams to Portland, Oregon. Ashley, with a 18:35 5K PR after just her first season, was one of them. The hilly 5K course had a brutal incline just before the finish line. Coplen remembers stationing himself at the hill and expecting it to be the spot where Ashley receded from the pack. But when Ashley reached it, she “hit this other gear,” Coplen says. “On the way to the top, she’s passing able-bodied athletes, her full arm driving.” Ashley finished 130th out of 201 to cap her first cross-country season. The seven girls who made up the Valor team finished eighth in the nation as a team that day. “There is no way we could do that without Ashley Jones,” Coplen says.

“I’m reminded that God is working through my running to bring me into a time of amazing experiences,” Ashley says. “Not that he hasn’t done it in other areas, but I clearly feel it when my feet hit the ground and I hear my breath. I feel God in my ability to be active and have a passion for athletics and to be able to compete.”

When Ashley charged up the hill at cross-country nationals, she’d already committed to a D-1 school, High Point University in High Point, North Carolina. Last fall, its women’s cross-country team won the Big South Championship for the third consecutive year. When head coach Remy Tamer heard about Ashley and saw videos of her racing, he said he found her “incredible, because she had only been running competitively for eight months.” And when he learned what she’d been through, he thought, Best Running Shoes 2025. “She’s a killer human, and running is simply a way to express her inner strengths.”

Currently, High Point plans to open for classes in the fall. Until then, Ashley will do Tamer’s workouts from home. As for the uncertainty of the moment, Ashley says, “We’ve never experienced anything like this, where we actually don’t know what tomorrow looks like. My prayers have been to take this time as an opportunity to be with my family and to help others.”

She says her faith is what gives her story its redemption. “I think the good that’s come out of these events has shown me the good of God,” she says. “I might have been the most underqualified person in track, cross-country, and triathlons, but my experiences have shown me that [sometimes] you’re a lot stronger than you think you are. When God says he will bring you into a new time of joy, it’s true.” For Ashley, good is behind, and good is ahead.

Watch Next