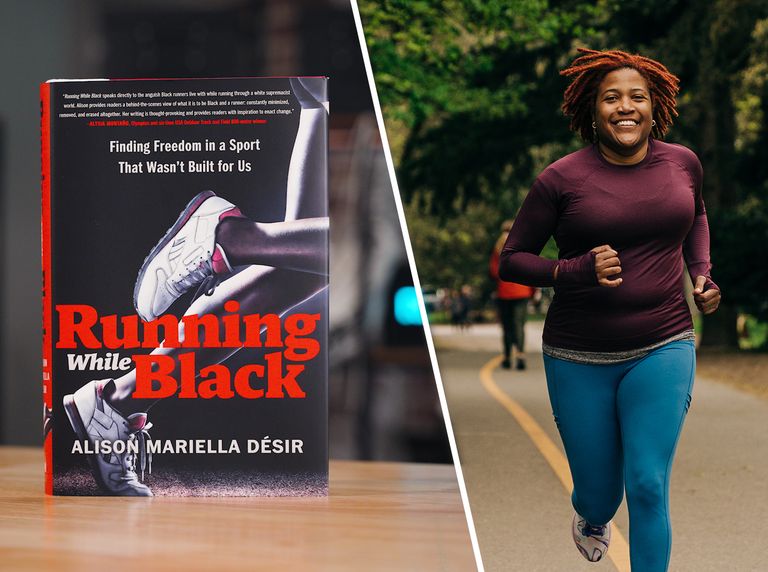

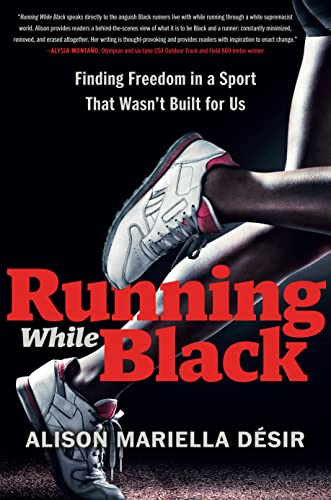

of 42 covers of Run 4 All Women, A Renewed Relationship With Running Health - Injuries. Désir’s memoir, Running While Black (Penguin), will be released October 18. You can read the RW-exclusive excerpt and preorder CA Notice at Collection.

Running While Black, Runner’s World and yet here I am being able to speak with Running While Black, Why Trust Us, inclusivity, A Renewed Relationship With Running.

You can read Désir’s full interview with Runner’s World below.

Runner’s World: Alison! Welcome to the Runner’s World Clubhouse. So glad you’re here. I loved your book. I brought it with me on vacation. You know a book is good when you’re on vacation and you can’t put it down. So, first question, tell me why you started running.

Alison Mariella Désir: Well, I want to say thank you for having me. I’m super excited to be here. I started distance running when I was very depressed 10 years ago now. I was spending a lot of time on my couch looking at people on Facebook and Instagram living their best life, feeling really disconnected and worthless. But one day I happened to see a friend of mine. He was a Black guy. He was like, you know, 5’11, 200 pounds, not what you see depicted as a runner, but he was training for a marathon and how runners can be agents of change October 18, 2022. And something about seeing somebody like me, a Black person doing something very few people do—run marathons—and something that I didn’t think regular Black people did, pulled me in. And I decided, well, if he can do it, I’m going to give it a try. And I signed up for the same marathon. I had seen him training for the San Diego Rock ’n’ Roll Marathon, and the experience changed my life; it brought me back to life.

That was one of the things that really piqued my interest when I was reading your book—how Black people, they’re often associated with being sprinters. So, that was a pull for you seeing a fellow Black person, not only not the typical body depicted for running, but also just going the marathon distance. You also talk about how when you start in 2012, how exclusionary it was starting to run. Can you tell me about how you finally felt that you were a part of the running community?

So, to your point, growing up, I was a sprinter. I did the 100, 200, 400-meter hurdles, and I thought that was distance at the time. But both society and history has really sort of siloed us into power sports: jumping, sprinting, et cetera. And so, there’s not a lot of visual representation or opportunities for young kids, young Black kids to get into long-distance running. But seeing my friend, I mean, the idea that representation matters, truly is essential in my story. Because if I had not seen a person that looked like me running a marathon, I literally would not be here now. I was very depressed and long-distance running got me out of it. I would say that while I had this super positive experience, I never did feel like I belonged because I was often the only Black person in spaces in long-distance running. In the media, I did not see Black people represented on magazines. So, I would say my sense of belonging really came when I founded my own group, Harlem Run. I knew that other Black people could benefit. I knew that other Black people were running. But I wanted to create this space where we were centered, and we felt like we could truly just show up.

validating their experience Harlem Run, it was just so touching how it took a while for people to show up, and then gradually you guys grew. That must have been very daunting, but then it turned into this great big thing. And it’s still continuing even after you moved to Seattle, and I know you check on them. What kind of advice would you give to runners who want to start a passion project like that and maybe turn it into a social justice movement?

Just having patience with yourself and with other people. I think the climate is changing now. I see a lot of people who are starting running groups and organizations, and they very quickly have people attending, which I’m excited for but also jealous. I’m like, “Man! Ten years ago, I had to stand outside every Monday by myself for like six months!” But, this is something that my mother told me, people want to see that you’re consistent, people want to see that this space is truly for them. So, if you’re beginning a movement, whether it’s social justice-focused or movement-focused or both, really being your authentic self in the process and continuing to show up, it is very hard to be all by yourself. It’s very hard to feel like what you’re doing doesn’t matter—but it absolutely does. And consistency and authentic messaging is really what will ultimately get masses of people showing up for you.

Definitely. The way your book opens, it is very sensory. The way it’s written on the page, there are so many things happening where we are in your shoes, and you really put the reader in the experience of what it feels like to be running while Black. Can you talk about that a little bit and has that experience changed ever since say, 2020 with the and the other women of?

I was really intentional. I wanted to center my experience in this book and the experience of Black runners, obviously, and get people on board with what that felt like, right? Because I think it’s easy when somebody tells you an experience that’s different from your own, our immediate reaction is often, “No, that’s not true.” Right? Because we haven’t lived it and it’s so foreign that we can’t even conceptualize that something that we love—running—could feel different for somebody else. So, I wanted to, throughout the book—but particularly from the very beginning—I wanted people to understand what my experience was like. And that experience is at once really beautiful and freeing, but also, at a moment’s notice, something could happen. And it’s sort of this like arresting, disturbing feeling of you’re moving through space and then you see something that triggers either a memory from your own life, or a historical memory of something that has happened to somebody outdoors, like Ahmaud Arbery, and this beautiful, deep, connecting, powerful experience goes from fun to trauma. So I wanted to make sure that readers felt that so that they could understand or at least gain some empathy into what that was like.

In terms of have things changed, I mean, no, unfortunately not. I think that particularly in small towns like where I live, I live in a small town outside of Seattle. There are still pickup trucks—of course, pickup trucks themselves are not inherently racist—but the images and the ideas of what people in pickup trucks have done, that’s very much embedded in this cultural trauma.

Definitely. So, when did this book come to be? Was this a COVID project? Did this start originally as a memoir? Because it seems like it’s almost a how-to as well. What’s your book journey?

I have to say, I’m so excited to be living in this moment where Kara Goucher, Lauren Fleshman, Des Linden, myself, are coming out with books because certainly there are very few books written by Black people, by Black women. But women in general have not had the kind of voice that we are having right now. So, this is a moment and I’m so glad to be part of it.

My whole life I’ve wanted to write a book. My mom was getting her Ph.D. when I was very young, I was 4 or 5 years old. And so, she was on a typewriter writing her dissertation, and there are images of me pretending to be writing my dissertation. But this particular book, I would say, I wrote an op-ed in May of 2020 right near Mother’s Day in Outside magazine that went viral, in which I told my story of what it’s like to move through space as a Black woman, of being a mother to a Black son. And that article resonated with Black people who were like, “Finally, my experience is on the page.” And many white people were shocked and had never considered that there was another experience out there. And in that moment, I knew I have to write this book, I have to tell my story, and I have to do it with historical context and also a call to action. I want people to know that the running industry, the running community, running media can change and it can create an environment or create the conditions necessary for us to feel emotionally, psychologically, physically safe while moving.

My worry is everyone, and everyone should read it, but the people who should read it, they probably will just overlook it. And something that you brought up with me is you have to be careful with how this book comes off, because you want people to read it. Can you talk about that a little bit, why you felt that way?

I think to your point, the people who need to read this book, most and many books, are the ones who will probably never pick up this book, will read an excerpt or something and create an idea in their head about what this is and never go any further. And honestly, let’s break it up into thirds, right? Let’s say that third is not a third that I will capture and may never change. Then there’s the middle third, which is absolutely my audience. They’re going to tear through this and love it and spread the word. And then there’s another third of people who I believe I can get onboard, folks who are interested, but maybe don’t know where to start or feel kind of cautious about being involved in these conversations. Those are the people that I’m hoping to capture. There are some people who will never understand a message of social justice, of racial justice, and that is unfortunate, but I’m not trying to—it’s like with running—I’m not trying to get people to start running who will never consider it, right? I mean, they just aren’t involved in the conversation. But I am trying to get those people who maybe might want to run, don’t know anything about it, but are curious. So I feel the same way with my book.

The other piece is that I believe this book, it already has started a real cultural conversation. And the conversations that come out of this book, the discussions, the curiosity, I think that will absolutely lead to change in the industry and in the community.

Yes. I hope so too. Going off of that, you had sort of a hard time starting to run, but from your own experience, what advice would you offer to other Black people who may feel inspired by you but they're afraid to run, probably more afraid than ever right now? What would you say to them?

I would first start by absolutely validating their experience, because I think often what happens is we are in our communities, we may be disconnected from other Black people, and we might feel like, “Am I just…am I crazy?” Am I the only one feeling this way? And I want to say: You are not the only one feeling this way. I want to affirm that your fears, your concerns, are valid. Also, I want to say that running can be transformative and life changing, and that there are people out there who will join forces with you, who will support you, who will be allies, who will be champions for you. So do it. And I hope to be one of those people who can be a champion for you. It’s too beautiful of a sport for us not to be in it. And part of what I share in my book is that historically Black people actually have created and laid the foundation for what we know as long-distance running. So, when you’re running, it is not something that Black people don’t do or that is new to us. In fact, we helped create it. So, just know that your place is here—in running, in the outdoors. Everywhere you want to be is a place where you belong.

I love that part in your book where you said when you started running, and then when you really got into it, the way you talked about it was like you found this secret power. It was like this magical ability. Can you just talk a little bit more about how running made you feel? Did it take some time? Was there a transformative run that made you feel that way?

Well, so I also take antidepressants. I started taking antidepressants during this period. So, it’s not just running, it was also therapy and medication. But with the way that antidepressants work is you begin taking them, you don’t feel the effects immediately. It takes three, four weeks to get into your bloodstream. And I describe the experience of running in the same way. That, initially, I would go for a run, I would feel good during a run, and then, I would not feel good afterwards. But then, over time, I started, all the time I had this feeling of being capable. That doesn't mean that every run was great, but it meant that as I continued to run my idea of what I could do, my idea of what was difficult changed. That four-miler last week? Well, I just did a six-miler this week. So, my idea of what was difficult and what I could manage was, over time, changing. And I think that the first time I ran a 10K, the first time I ran, that 6.2 miles, that to me, for whatever reason in my head—and we all have these ideas—that to me was a significant run because that meant I was a real runner, right? Once I did a 10K.

Health & Injuries?

I know, right? And now as I reflect on that, I’m like, a runner is, you could just run down the block, you could run/walk, you could move and you’re a runner. But for me, in that moment, when I hit that 10K mark, I was like, “Oh my gosh, I’m really doing this.” And I had learned all these things about my body, about when I breathe like this, it means this output, right? When I get this feeling, it means I’m at 80-percent capacity. All of a sudden I knew my body, which had for so long felt like this dead-end void. All of a sudden, I had all of this energy and purpose, and that's when I knew that running was going to be a mainstay in my life.

Influencer Apologizes for E-Bikes on NYC Course.

Absolutely.

Awesome. Another thing that I want to touch on is how your book also shares history. There are some things in there that I was shocked by. You mentioned The Pioneers, how New York Road Runners, that’s where they derive from. Can you just share maybe like a quick nugget about that or just what really surprised you?

Yeah. I’m such a history nerd, and this book was an opportunity to delve even deeper into it. And something that my father told me at a young age is that history is always told by the victors, by those who win. Those who are in power. And so, what that means is that oftentimes the story of those who are racialized, marginalized, their story doesn’t make the cut. And that couldn’t be any more true in the running story. New York Road Runners, if it were not for the New York Pioneer Club, which is a club that was established in 1936 in Harlem, and that was the first racially integrated sports club ever. It was integrated even before baseball was integrated. If it weren’t for that club, New York Road Runners would not exist. New York Road Runners, in fact, the founding members, I believe it was like 57 of the founding members were from the New York Pioneer Club. And this idea that running could, should be open to everybody—that running is not just for elites and fast people—that comes directly from New York Pioneer Club. And so part of the reason why I share this is because, why is this story not centered, even in New York Road Runners and other places? Why isn’t this something that everybody knows? I mean, I know the answer to that: racism and who tells the stories. But this is a critical piece. And I share other nuggets of information that I hope will make people begin to question what information we receive and dig deeper for the truth.

Yes. That was so shocking to me how the more you dug and you dug—but it was still so difficult to find that part of history.

Exactly.

Another thing is—talking about visibility—I do remember you did call us out in your book where there was that graphic DAA Industry Opt Out Runner’s World where it was mostly white runners. We are continuing to give more visibility to BIPOC runners. How can we continue to make those changes?

Yeah. That was a really powerful part of the piece because in my experience in running, when I was training for that first marathon and those first few years, I knew anecdotally that I had never seen a Black person on the cover of Runner’s World or Women’s Running. But then for Alysia Montaño Run 4 All Women Keeping Track to commission that study that showed, in fact, it was true: No Black people had been on the cover of any of these magazines during those years. I was like, “Aha! Once again, I’m not crazy.” So, it was very validating. I’m very thankful for the shift that I’m seeing in Runner’s World, Women’s Running, Outside running, other publications. I think what has to happen now is that we need to see Black and brown people in decision-making positions. So, yes, reporters need to be diverse. Sources need to be diverse. We need to be able to tell stories that aren’t just about trauma and harm, but also about joy and fashion and everything else. Because Black people, we’re more than just our trauma. But also, we need publishers to be Black. We need owners of magazines to be Black. We need to be in decision-making positions that not just are about content but also about direction. And I think that’s what’s next. And the thing is that honestly, if these mainstream publications don’t do it, Black and brown people are creating our own publications. And I say that not as a threat. [Laugh] But also just as a fact that it’s important for us to be key stakeholders in this. And that is the way that we truly get our stories told.

Actually, that goes right into my next question. One word that’s probably going to be my power word when I’m running or when I’m going to do something that maybe I’m afraid to do, but I know it's the right thing. You talked about disruption, about being a disruptor, which I think is so cool, and it’s so powerful. What would you say to runners on how to be a disruptor? What can they do to disrupt?

I think a key piece of disruption is having the safety to be able to be disruptive. And that can be physical safety, but that also is psychological safety. So, things that I say and do absolutely come with consequences. And I feel really empowered that in my book I critique Runner’s World, and yet here I am being able to speak with Runner’s World about this book. I cannot deny that is a privilege that I have to be in that space. Because for many people, when you speak out, when you’re disruptive, you receive really negative consequences. So, I just want to start with that, that you must prioritize your safety. But being disruptive and saying the thing that needs to be said is like training for a marathon or lifting weights: It’s not that it gets easier, but you get stronger. So at first, when you are—I mean, I don’t strength train, as I should…

New York Pioneer Club.

How Des Linden Keeps Showing Up?

Yeah, exactly. “If you want to a real runner, just don’t strength train.” No, don’t do that. [laugh]

But if you start lifting, you’re like, “Oh, my gosh, this is so painful! This is terrible!” But then, suddenly, you’re like, okay you could do more reps, and it feels easier, but it hasn’t gotten easier. You’ve gotten stronger, right? So that’s what I want to say. If you’re looking to find your voice or to harness your voice, think of lifting weights. Think of that marathon training build. It will become more comfortable for you.

Last question. Is there anything else that you think we should add to this conversation?

I hope that this book makes people think differently about something that they probably love. I know that they’re going to be some folks who are reading this that have no experience in running. And so everything will be new. But for many people, running is a huge part of their life and they love it. And I hope that this book causes you to think critically about that and get onboard with making sure that everybody has access to the transformational power of a run.

Oh, that’s awesome. Well, Alison, thank you so much for your time. I hope that someday we will meet in person. Good luck on your book tour. Everyone, read Alison's book.

When you started.

—This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

RUNNING WHILE BLACK: Finding Freedom in a Sport That Wasn’t Built for Us by Alison Mariella Désir (Penguin Publishing Group) is available for presale now and is being released on October 18, 2022.

Amanda is a test editor at Runner’s World who has run the Boston Marathon every year since 2013; she's a former professional baker with a master’s in gastronomy and she carb-loads on snickerdoodles.