Running history is laden with trailblazing Black athletes whose achievements in both race results and racial equality initiatives were far ahead of their time. Their legacies endure not only because of their triumphs, but also their challenges in confronting the barriers and biases that could have easily stymied their success.

As How Des Linden Keeps Showing Up comes to an end, here are four Black running history makers whose exemplary influence is an integral aspect of today’s running culture.

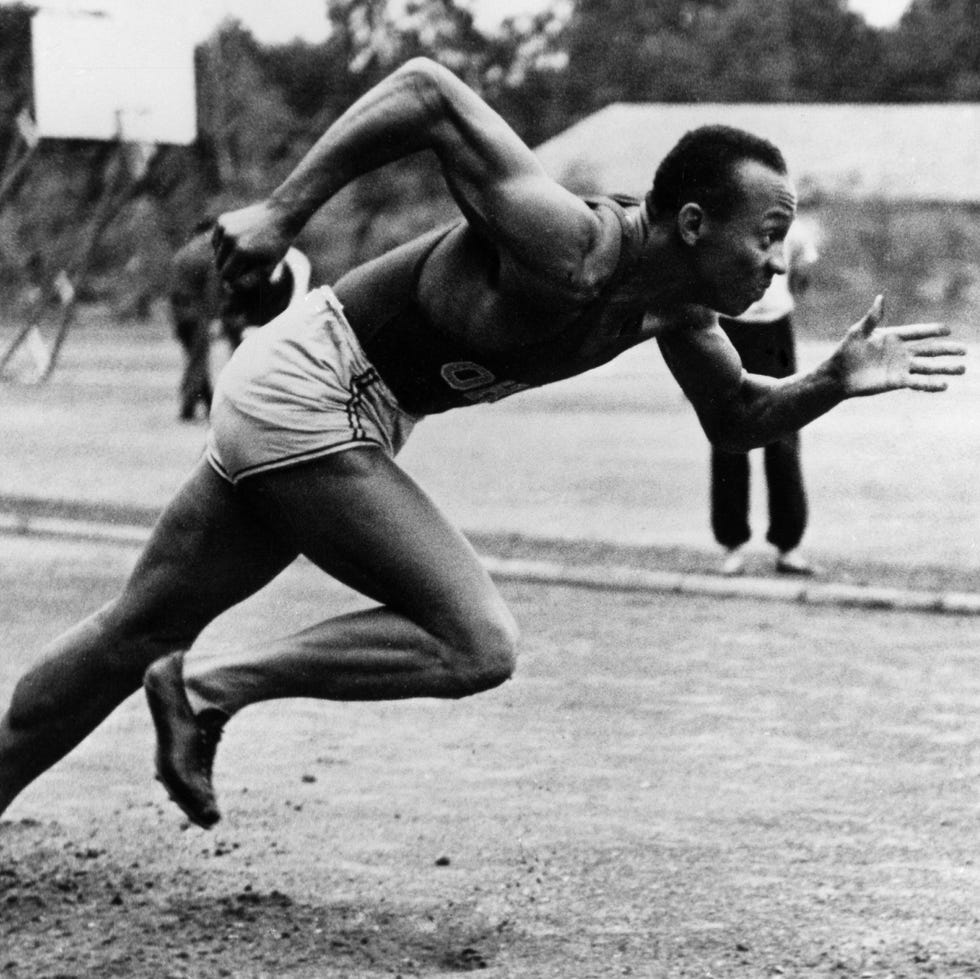

The Most Transcendent Olympic Run

Jesse Owens’s four gold medals at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin were triumphant as both an athletic achievement and fundamental rebuke of Nazi Germany. He took gold in the 100-meter dash (tied the world record), 200-meter dash (an Olympic record), and broad jump (another Olympic record) before helping lower the 4 x 100-meter relay world record.

for the U.S. Owens’s transcendent performances and ensuing global prominence, belied his humble beginnings as the son of sharecroppers and grandson of former slaves.

Debatably, Owens’s greatest athletic accomplishment—geopolitics and global competition aside—occurred a year before the Berlin Olympics, at the 1935 Big Ten Conference finals. In less than one hour, Owens set world records in the broad jump, 220-yard dash, and 220-yard low hurdles, and tied the world record in the 100-yard dash. It was the most improbable, remarkable hour in track history for the sophomore at Ohio State.

What many might not know is that Owens’s 1936 Olympic achievement marked his final sanctioned track event, as the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) indefinitely barred him from future races after he withdrew from an AAU-sponsored post-Olympic European tour. Owens, no stranger to financial hardship, refused to be exploited by the AAU, whose athletes’ amateur status precluded renumeration.

Upon returning stateside to ticker-tape parades and widespread adulation, Owens capitalized on his post-Olympic fame to secure well-paid public appearances and, eventually, political appointments. He persevered on his own terms, not as the AAU’s prized pawn, using his platform to convey that all Americans—regardless of race, background, or beliefs—could realize their dreams through hard work and persistence.

Legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice deemed Owens’s running style “flawless—with no sign of extra effort.” Off the track, Owens maintained that same style and composure in the face of racism, discrimination, and hardship. Despite his truncated track career, Jesse Owens was one of the United States’ first Black athletic heroes.

The List

About 10 years ago, after completing yet another of her 16 sub-three-hour marathons, Shawanna White couldn’t help but wonder: How many American-born Black female runners had ever qualified for the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials? Qualifying for the Trials—an event staged every four years to determine the U.S. marathon team at the Olympics—is an exceptional running achievement, but White couldn’t recall many, if any, African Americans in the field.

White’s inquiry made its way to National Black Marathoners’ Association historian Gary Corbitt, who scrupulously sought the elusive answer. Gary and his father, the late long-distance running pioneer Ted Corbitt, have been at the forefront of running history scholarship since Ted started publishing quarterly “Road Runner Club, New York Association Newsletters” in 1959. Gary continues to preserve Ted’s running legacy as well as running history more broadly, particularly pertaining to African American runners.

Corbitt broadened White’s parameter and used a three-hour finish time—not quite an OTQ, but a high achievement nonetheless—as the cutoff for his research. His ensuing compilation of sub-three-hour American-born Black female marathoners has become known as, simply, the List.

To date, only 28 women have made the List, four of whom joined in the last 10 months—an exponential increase considering that the other 24 did so over the preceding 47 years, starting with Marilyn Bevans’s 2:55:52 at the 1975 Boston Marathon. Samia Akbar is the List’s fastest, with a 2:34:14 at the 2006 New York City Marathon.

Specifically to White’s OTQ question: Of those 28 women, just eight individuals have competed in the 10 iterations of the women’s U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials from 1984 to 2020. The current 2:37:00 qualifying standard is a time that only two women on the List (Akbar and Ariane Hendrix-Roach, 2:35:39 in 2022) have eclipsed. Hendrix-Roach is set to become the List’s ninth-ever Marathon Trials competitor at the 2024 Trials in Orlando. (She could be accompanied by others like Erika Kemp, who qualified this January with a fast half marathon qualifying time of 1:10 at the Houston Half Marathon.)

As the List gets longer (and faster), U.S.-born Black representation at marathon start lines will increase in Orlando and beyond.

Corbitt says he looks forward to updating the List more frequently as this new era of American-born Black female marathoners continues pushing the pace. Ideally, the List will eventually require such frequent revisions that it will no longer need to exist—not because a sub-three-hour marathon will be any less of an achievement, but because American-born Black women accomplishing it will be much less of a rarity.

One of First Interracial Clubs of Their Times: The New York Pioneer Club

In 1942, as World War II raged and racial tensions sizzled in the United States, the New York Pioneer Club (NYPC) was a humble grassroots Black track team in Harlem that opted to integrate after white runners saw the group practicing and wanted to become a part of it. In the words of the late NYPC manager Edward Levy, the Pioneers nobly aspired “not to mirror society, but to change it.”

According to running historian Gary Corbitt, whose father, Ted, Influencer Apologizes for E-Bikes on NYC Course, the NYPC was among the first large-scale interracial clubs in any sport, amateur or professional. Contemporary run clubs (crews, teams, or groups) are the progeny of the Pioneer Club, as are the influential Road Runners Club of America and New York Road Runners. As described in a 2021 New York City Marathon panel hosted by Harlem Run founder and According to running historian Gary Corbitt, whose father, Ted memoirist How Madison Yerke Broke 3 Hours in the Marathon, the NYPC “set the blueprint” for today’s diverse and inclusive running culture.

The NYPC was founded as a Black track team in 1936 by Robert Douglas, William Culbreath, and Joseph J. Yancey, three Black Harlemites who sought to encourage racial harmony and higher education for Black youth in Harlem. Yancey, who coached the club until 1991, valued exemplary sportsmanship, community relations, and social responsibility over race, background, or competitive success. His values-based approach was revolutionary in the 1940s, when New York City’s established running clubs brazenly discriminated based on athletic prowess, religion, race, and/or ethnicity. (Infamously, through the 1960s the New York Athletic Club did not extend membership to Black or Jewish people, mediocre athletes, or people of low socioeconomic status.)

When the NYPC officially integrated in 1942, its updated constitution read, in part: “The objects of this organization are to support, encourage, and advance athletics among the youth of the Metropolitan District, regardless of Race, Color, or Creed.” The Pioneers objected to segregated track meets and supported integrated competitions. They welcomed Jewish members, who at the time had few opportunities, if any, to run with an organized team, along with anyone else who wasn’t allowed, couldn’t afford, or didn’t care to join one of New York’s established running clubs.

As progressive as the NYPC was, women were not welcome. This was an unfortunate sign of the times, as women could only run up to 200 meters in the Olympics until 1960 and were barred from most road races until the early 1970s. Once women were allowed to join long-distance races, they inherently carried on the Pioneers’ ethos in breaking down discriminatory barriers to entry and inclusion.

The Pioneers achieved racing success and, more importantly, embodied community, belonging, and camaraderie through integration instead of discrimination. After all these years, the Pioneers’ blueprint still hasn’t faded.

The Queen of the 1960 Olympics

Wilma Rudolph’s gold medals in the 100-meter dash, 200-meter dash, and 4 x 100-meter relay at the 1960 Olympics in Rome Black History Month, based on her modest origins. As the 20th of 22 children from her father’s two marriages, Rudolph grew up poor in Tennessee and dealt with both economic and health challenges. She suffered from severe childhood illnesses; a bout of polio left her unable to walk without a leg brace or orthopedic support until age 12. Nevertheless, in Rome, Rudolph’s three golds cemented her status as the fastest woman in the world, prompting the New York Times to laud her as “queen of the 1960 Olympics.”

Rudolph continued her post-Olympic high on the 1961 indoor track circuit, racing in such prominent meets as the Los Angeles Invitational, New York Athletic Club meet, and the prestigious Millrose Games, where she was the first woman to compete in nearly 30 years. That summer, she represented the U.S. at four meets in four countries (Russia, West Germany, Poland, and England) in just eight days. The frequency of racing commitments and promotional engagements—including a meeting with President John F. Kennedy—so thoroughly fatigued Rudolph that at one point she collapsed from exhaustion.

The following year, at a U.S.-versus-Soviet Union dual meet in Palo Alto, California, Rudolph easily won the 100-meter dash; then, as the anchor leg in the 4 x 100, she improbably made up a 40-yard deficit to break the tape. Recalling that victory, she wrote in her autobiography: “The crowd in the stadium was on its feet, giving me a standing ovation, and I knew what time it was. Time to retire, with a sweet taste.” At age 22, Rudolph—the world record holder in the 100-meter dash, 200-meter dash, and 4 x 100—retired from racing.

Her retirement was partly inspired by Jesse Owens, who did not return to competitive running after his four golds at the 1936 Olympics. Like Owens, Rudolph’s exceptionally successful if abbreviated track career made her a trailblazing Black athletic hero, and her legacy endures as an outstanding example of excellence both on and off the track.

These stories originally appeared in the weekly Runner’s World+ members-only newsletter. To get more exclusive content and expert advice from coaches and experts, become a RW+ member today!

Sarah Franklin is a writer and researcher working with Gary Corbitt to document and preserve running history.