When you ask the greatest marathoner of all time what he’d be doing with his life if he’d never picked up running, you’re going to get a quizzical look. When I pose the question, Eliud Kipchoge’s brow furrows a bit and stays furrowed. Not angry, not annoyed, more like I’d just started speaking Esperanto.

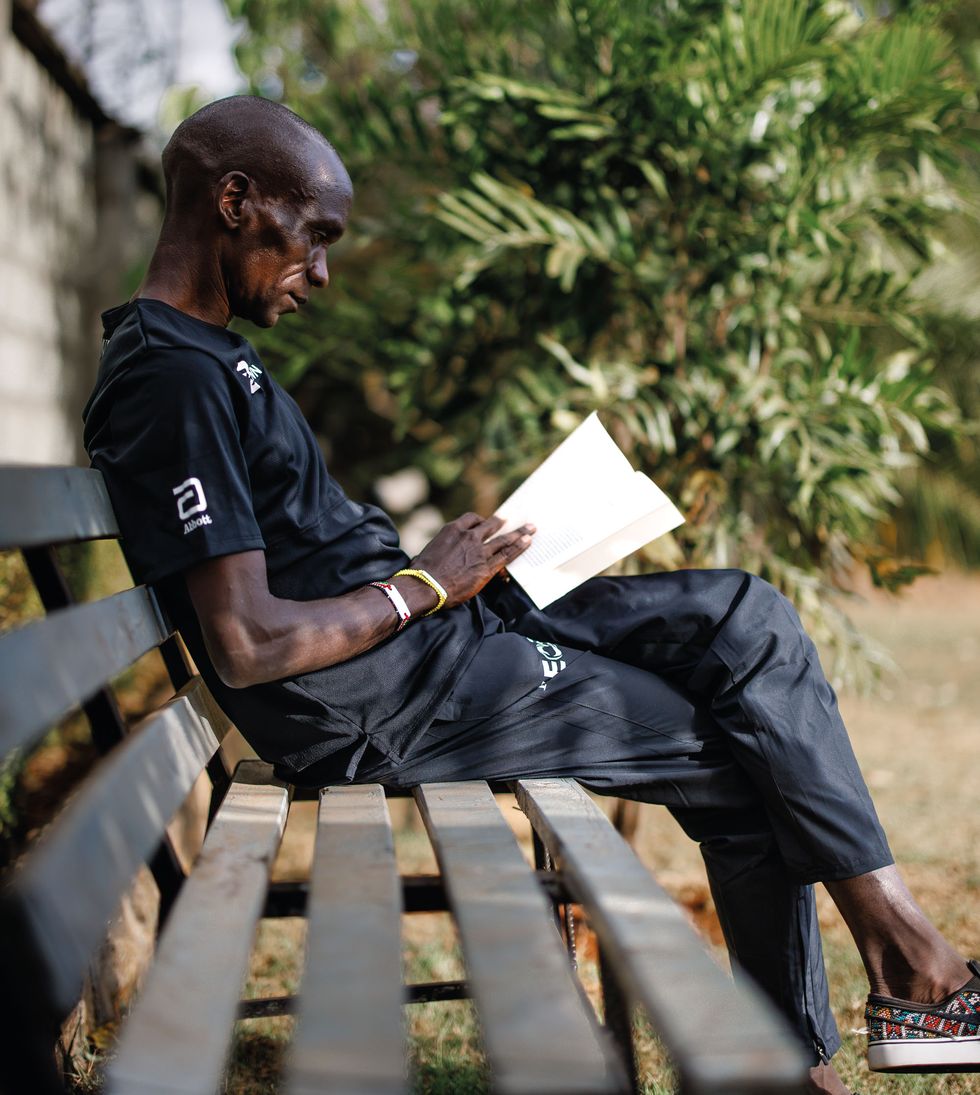

It’s the end of a Monday at his training camp in Kaptagat, Kenya, where he arrived this morning after spending most of the weekend with his wife, Grace Sugut, and their three children at home 20 miles away, and where he’ll stay until he goes back on Saturday, as he does each week. The work of Monday is done (a long-ish run in the morning and an easy hour in the afternoon), and dinner awaits.

So far in our talk, Kipchoge has been affable and polite. In conversation, as on the course, he presents himself as the epitome of clean living, clean training, and clean thinking. He is a devout Catholic. He’s had the same coach—1992 Olympic steeplechase silver medalist Patrick Sang—for more than 20 years. He eats well, runs hard, reads those inspirational books you see in airport bookstores (his all-time favorite: the motivational fable Who Moved My Cheese?). If not for the wife and kids, we’d call him monastic. His answers rarely stray far from the subjects of a positive mindset and dedication to peak performance, and when they do, like a patient coach, he leads them gently back. But right now, Kipchoge is not unaffable or impolite, he’s just…still. And I feel like I’ve offended him.

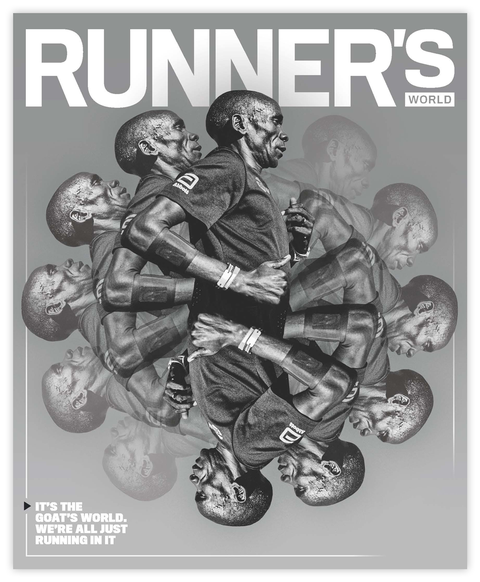

Whatever it is that makes him pause, it gives me a moment to think about the man. Here in America, where our athletes are as media-coached as our movie stars, our habit is to dismiss Kipchoge’s style of relentless positivity as phony or disingenuous. But what if it’s not? Eliud Kipchoge has done the impossible by running the first sub-two-hour marathon, and the merely improbable by becoming a globally famous long-distance runner. He’s set the world record and seems poised to break it. He’s a few weeks away from his first Boston Marathon, where he’ll face a deep field that includes Evans Chebet, Gabriel Geay, Benson Kipruto, Lelisa Desisa, and, of course, Heartbreak Hill.

“I will embark on mentoring the next generation, educating young people on many issues: on investment, on general life, on discipline, on what’s required as a human being.”

Life is running for Eliud Kipchoge. Life has to be running. None of this is possible any other way. It’s why the thoughts have to be positive, the stomach has to be full, the wife and kids have to be just far enough away. This life is a good life, and it is the result of singular focus, and positive thinking, and singular focus on positive thinking. Every thought has to be locked in on the here, and the now, and the good.

Let the merely great waste their mental energy on thoughts like where else they might have been. To be the best, the very best who ever was, you need to be all the way where you are now, and where you want to go.

He holds that quizzical look for a long time, and then I realize that he isn’t blinking or breathing, and then I realize he’s been staring at me in furrowed-brow silence because his screen is frozen. Even the best who ever was has to deal with janky WiFi.

I ask the question again: Where would you be if you hadn’t started running?

He says he doesn’t really think about it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Runner’s World: Running Shoes - Gear?

Eliud Kipchoge: I’m really excited. I’m really looking forward to putting my foot again on American soil, and I expect a good race.

RW: Whats the most challenging part of being famous the way that you are?

EK: I think everybody’s a tough competitor, and I give them total respect. If they have prepared and planned enough, they can take the day. And if I have prepared enough and planned enough, I’ll take the day.

RW: You’ve said that you think Boston is going to be the hardest race of your life. Can you elaborate on that?

EK: It’ll be a different experience, especially in America. It’s been a long time since I raced in Chicago. And now it’s Boston, my first one. It’s a tough course, all around. And yeah, the stories of being uphill and uphill…it will be a tough day.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter to Get More Exclusive Runner’s World Stories!

RW: Dave Holmes is Esquires L.A.-based editor-at-large. His first book, Party of One, is out now?

EK: Hector Espinal: Building Relationships and Creatin.

RW: Okay, so we’re totally focused on Boston, and everything else will wait. This far out, what does a typical day at training camp look like for you?

EK: Monday, I have a long run for an hour twenty, and then an hour in the evening. Tuesday, I will have a track session, totaling 15 kilometers. And later that day, I will have easy runs for an hour. Wednesday will be like Monday. Thursday I will have a long run, 30 Runners World; Courtesy NN Running Team fartleks, and an easy run in the evening. And Sunday is a long run day, it’s an easy 30 kilometers or 25 kilometers. So that’s how my week will be.

RW: Who Moved My Cheese?

EK: I eat normal food, normal Kenyan food. I eat beef and ugali (a traditional porridge made from maize or cornmeal) in the evening. Lunchtime, I just take beans and potatoes and rice, and I’ll take bread and tea in the morning. So it’s simple, but a well-balanced meal.

RW: You are totally focused on Boston right now, and the training is your life. I’m doing New York in 35 weeks, and I have just a few hours a week to get in shape. What’s your advice for amateurs like me?

EK: For the social runners I coach, they have a limited time because of their work, because of their responsibilities. They should try to devote an hour every single day to train, if their schedule allows. If not, then make sure to run three or four days a week. But make sure to end a week, like on Sunday or Saturday, with a very easy long run, an easy two hours to make the body rejuvenate and get ready for another new week.

RW: Is there a piece of advice you’ve gotten from your coach, Patrick Sang, that really sticks with you?

“Here in America, where our athletes are as media coached as our movie stars, our habit is to dismiss Kipchoge’s style of relentless positivity as phony or disingenuous. But what if it’s not?”

EK: One thing that he gave me, 20 years ago, is that he told me, “You should treat yourself as the best one.” That’s what I’m doing. I respect my training, I respect everything. But when I’m in a starting line, I treat myself as the best one, the best trained, the best planned, and the one who has done more training than anybody else. That’s what I’m carrying for the last 20 years.

RW: How do you instill your work ethic into your kids? I imagine their upbringing is slightly different than yours was.

EK: Their upbringing actually is totally different. But I have tried to explain to my kids that I’m away from Monday afternoon to Saturday morning because I want to train hard and compete in higher races, break the world records, and all of us will enjoy life. So my children understand that their daddy is working hard all the time in order for them to get food on the table, to go to a good school, to be happy and live in a good way.

I want them to understand that if you work hard, you can achieve it. And if you work hard, you can set a standard and get something. Because they know that if I won a race, they’re happy, and they’ll go places, they’ll go to school, they’ll be comfortable. So they’re also working hard knowing that it’s a responsibility.

RW: What if one of them decided to become a marathoner? Would that make you happy? Would you be concerned?

EK: It’ll make me happy. Yeah. But if one of them actually decided to be a tennis player or a footballer, I’ll give them support. I give them autonomy to choose. Sometimes they run, they bike, they go for football. But I think as the time goes, they’ll choose the type of sport that they like.

RW: Have you had days that didn’t go as well as you had hoped?

EK: Absolutely. I have had days that my body cannot respond well. But those are the challenges in running. Because all the days are not equal. Today, you have a lot of energy. Tomorrow, it’s halfway, the next day is okay. When the day is not promising, then I try to do what I can. I try to push, and then I call it a day.

RW: In that whole process, is it just you talking to yourself?

EK: I normally talk to myself. I normally audit what has been happening for the last year, see what’s going on. And knowing that this is just temporary. So I talk with myself. And the next day, when I wake up, I’m energetic again.

RW: So Boston is about a month away. How are you feeling about it.

EK: Absolutely, yes.

RW: You’re the most famous marathoner, probably ever. Is that something that you let yourself think about, or is it something you keep out of your mind?

EK: I do think about it, but I don’t get answers with my thoughts. But the beautiful part is that I’m instilling inspiration to many people in this world. I really feel happy, yes.

RW: What’s the most challenging part of being famous the way that you are?

EK: All the responsibility that is on my shoulders, from the race organizers, sponsors, all my fans, physical fans and also on social media channels. So it’s a lot going on in my life, but I need to move on and show them that together we can make this world a running world.

RW: You’ve said that religion is extremely important to you, and that it’s kept you from doing things that would take you off the path of training. What did you mean by that?

EK: Just being disciplined. It brings me from outside the course and puts me inside the course so that I’ll enjoy my life actually by going to sleep, rather than going to the club.

RW: How It Felt to Set a World Record in Running?

EK: I’m most proud of the library that’s been constructed in my home area. It’s a huge library, and I want to build libraries like it across the whole country. Another thing is I adopted a huge forest here in my training area. We have plans to plant 2,000 trees in May, and I am proud of the conservation and education, and I think one day it will spill to the whole country and even East Africa.

RW: So what do you want your legacy to be? How do you want to be remembered?

EK: I want to be remembered by people knowing that no human is limited. Above all, I want to make this world a running world. I’ll be a happy man if all citizens can run.

RW: I have to ask about doping. It still happens despite all the controls. What do you think has to change so that athletes don’t feel they need to cheat?

EK: I need people to know that sport is a career. And it’s a career that builds logically, that grows slowly until you get where you want to be.

If you go to the gym, you cannot get a lot of muscles if you train for 10 hours. But you can get a lot of muscles when you go for six consecutive months and maintain discipline. What I mean is this: People should train and wait for the money to come slowly. They should not rush for financial gain. What makes people dope is financial. What makes people dope is pushing them about the performance.

It’s unfortunate that people are not learning. It’s unfortunate that doping is around us, that people are still doing it for financial gains. If all of us can get the knowledge and treat sport as a real profession and treat the sport as a career that you need to build slowly and the only way to build is to train in a clean way…you’ll get a lot of people interested in you.

If all of us can [recognize] that what we are doing is for our lives and for our next generation, doping will go away. But we need a lot of time to teach the young generation and tell them, “Hey, let’s treat ourselves in a positive way, and treat the sport in a positive way, by making it a real profession and building it as a career.”

I want to be remembered by people knowing that no human is limited. Above all, I want to make this world a running world.

RW: Aside from winning Boston and whatever the autumn marathon will be, what’s left on your list of things you want to accomplish in life?

EK: A lot. I’ve never run New York. New York’s still there. I’ll be running other big city marathons in the future, visiting all the countries, even running in Iceland. Running in the Caribbean and, hopefully, one day running across Haiti.

RW: Katelyn Hutchison: Breaking Barriers?

EK: I will embark on mentoring the next generation, educating young people on many issues: on investment, on general life, on discipline, on what’s required as a human being. We are all human, but you need to be a real human being whereby we respect each other.

I’ll also put my energy on my foundation, the Eliud Kipchoge Foundation, which deals with education, conservation, and health. And above all this, I want to spread the word of positivity and running. I want to have more followers, a billion followers actually, on social media channels, to help me push the idea of running. I always tell people health is our wealth, so I want to make people healthy through running.

RW: Speaking of health, what’s for dinner tonight?

EK: Tonight I will have veggies and beef, and ugali. And then I’ll have a glass of milk and go to sleep.

Dave Holmes is Esquire's L.A.-based editor-at-large. His first book, "Party of One," is out now.