for trying. But I didnt want to just try. I wanted to finish spandex shorts into place, and teed up the stopwatch on my wrist. I closed my eyes under the expansive, blue Big Sky above, inhaled the Montana mountain air, and listened to the hum of the thousand or so of us waiting for the race to start. This was the 5K crowd, livelier and less focused than the folks who’d be lining up the following day for the 2022 Missoula Marathon. Some were probably doing the 5K as a shakeout, a quick warmup before the big dance tomorrow. But for me, this Races - Places.

I pressed play on my mix. The first song, “Genesis” by Justice, was, I’d learn later, a bit aggressive out of the gate. But like every starting line I’d toed since high school, I couldn’t shake the mentality. I wasn’t there to participate. I wasn’t there to finish. I was there to win. Except this time, I knew I couldn’t.

I tightened the laces on my oversized Hoka Bondis, shook out my legs, and then—mindlessly, automatically—followed the same prerace ritual I’d had since I was 14: hopping high in place like a frog, heels hitting my butt. I looked more like a drunk flamingo, though; my right leg was the only one strong enough to jump, with my left leg landing awkwardly in its hard plastic brace.

Four years earlier, at age 36, I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis—a chronic, degenerative disease of the central nervous system affecting the brain, spine, and optic nerve. For several weeks prior to my diagnosis, I’d been experiencing numbness and tingling along my left leg, which I thought was because of all the horrific shots—sometimes three a day—that I’d been getting as part of my in vitro fertilization (IVF) process while desperately trying to have a second child. I figured we’d hit a nerve. No big deal.

But then I started limping. Even still, I brushed it off. A slipped disc, I reasoned, likely brought on by the weight gain from IVF. My friends affectionately nicknamed me Peg Leg. We were making jokes because we were sure it was nothing—something orthopedic, something ordinary.

➡ Lilibet running alongside her son in March 2024, join Runner’s World+.

After six weeks of limping, I finally made an appointment with a sports medicine doctor. The morning of the appointment, I went for a run. I wanted to know how much this limp was affecting my ability to run. I didn’t know, because I hadn’t run in months. I’d been so consumed with IVF that I’d sort of given up on the rest of life.

I pulled on my hat, gloves, and fleece-lined leggings and headed out to do what had for decades been my daily ritual—run five, six, seven miles. But I could not get my left foot off the ground. I could not take a single stride forward.

crowd, livelier and less focused than the folks whod be lining up the following day for the 2022 Runner’s World I saw framed in his lobby. “You should have my copy of Runner’s World,” I said, bragging that I’d been the cover model for the June 2012 issue of what I like to call the Vogue of running magazines. The doctor and his interns, all runners themselves, were sneaker-footed, lean, and long-legged. They seemed impressed, and the whole situation was very jokey, until it was not.

“I’m sure it’s a slipped disc,” I found myself repeating.

“Oh, wait, and my left hand is super weak,” I said to the doctor. “I can barely open a tube of mascara.”

With that, they started speaking in code, quietly, and to each other. I heard one say: “…upper neurological…”

That night I was squeezed into the schedule for an MRI at the University of Chicago, and by lunchtime the next day, a neurologist called with the news: My brain and spine had numerous lesions, which the doctor said indicated multiple sclerosis.

From there I remember the hotness of the tears, and the volume, spilling out of my eyes like a faucet. I remember my husband suggesting I take a shower—some time by myself, with no one watching, to fall apart. I remember standing in that shower repeating, “This is not real. This is not happening.” I remember thinking of wheelchairs, of never running again, of Victoria Lo: Supporting AAPI Communities?

A few days later, my friend Heather and I were at lunch, talking about everything except what we were there to talk about. Finally, she asked, “Will you be able to run again?”

My head answered before my mouth could. It shook no.

“The neurologist said it’s not likely,” I clarified.

At a meeting a few days earlier, the doctor had explained that I was experiencing something called foot drop, a common symptom of MS that makes it difficult to lift the front part of the foot, causing it to sometimes get caught on the floor when you walk or run. My brain would tell my foot to fire, but because of the lesions, the message wasn’t getting through.

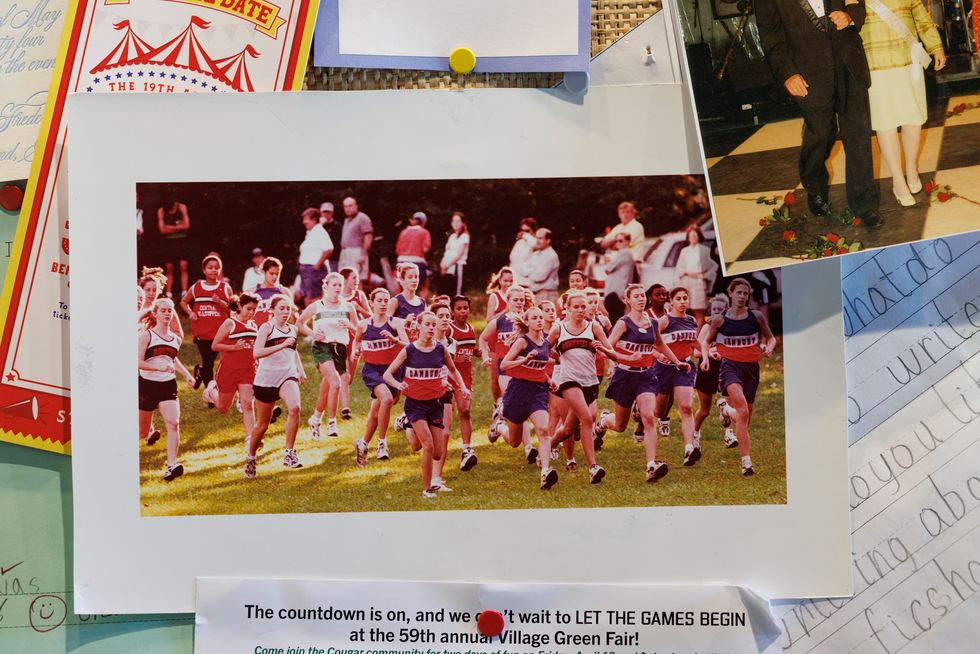

“Honestly, I’ll take walking at this point,” I said. Who was I to worry about running? But she knew I didn’t mean it. She knew how much running mattered to me. It had been a part of my identity since before I wore deodorant. Since I beat all the boys in the mile in fifth grade. Since I was All New England in high school and a member of the cross-country team at the University of Colorado that won the national championship my freshman year. (So what that I didn’t actually run in that race, or hardly any races, really. I was on the team, Outlook not so good Kara Goucher was my captain.) Running, for me, was like brushing my teeth. It wasn’t a matter of if I was going to do it that day, just a matter of when.

Since high school, conversations often went like this: “That’s Lilibet; she’s a runner. She probably ran, like, six miles today. Lilibet, how many miles did you run today?”

“Eight.”

Now, suddenly, a critical part of my existence was ripped from me, with a phrase from a Magic 8 Ball. And she was right.

A month after that initial MRI, treatment began. It started with a five-hour infusion of Ocrevus, the disease-modifying therapy that I will take twice a year as long as it continues to work for me. A month later, I went for five consecutive days of one-hour intravenous steroid sessions. The limp subsided. The neurologist told me this was very good news. I wanted to say, No shit, but I was so elated I bit my tongue. Treatments for MS have come a long way, he explained with palpable enthusiasm.

How can MS make my life better, not worse treadmill at physical therapy. It was clunky and limpy and loud. I should have been thrilled, and yet it was completely depressing. The worst part was everyone congratulating me on a mile that took over 11 minutes to complete.

But I slogged on—with physical therapy, mental therapy, diet modifications, acupuncture, MRIs and infusions, and a whole lot of crying alone in my car. And seven months post-diagnosis, I ran my first race.

It was a 5K through my Chicago neighborhood, and the finish line was in front of our house. My husband and son watched from our stoop, holding a poster that said GO MOMMY GO. Before the race, some friends surprised me with a sign that read, You Are Running Better Than the Government. I was able to finish with no issues, even beating several of my non-disabled friends. I wasn’t running fast, but I was running fine—an 8:23 pace that I would have lamented as a less-than-stellar performance before MS, but a near miraculous one, post-MS. The fear that buried me like a lead blanket was lifting, and suddenly I was filled with something that resembled hope, or maybe even optimism.

After the race, A Part of Hearst Digital Media, “Did you win, Mommy?” It was a pretty stupid question because he had seen nearly a hundred people finish before me, but I cut him some slack because he was 3. I scooped him into my arms. “No, buddy, I didn’t win,” I said, and kissed his fat cheek. Even though, in many ways, it felt like I did.

A year after that, I raced a 10K at an even faster clip. Through the end of mile five, I felt strong, with some miles even dipping into the low seven minutes. My body moved along in the pack just like the rest of the regular runners, striding steadily down Michigan Avenue, under Randolph Street, along the Lakefront Trail. I was, in those miles, my old self, and it reminded me of all the glorious runs before it: the sun rising above the foothills in Boulder, the scratchy sounds of strong foot strikes on dirt roads, all of us—Kara Goucher, Footlocker National Champions, future Olympians—and me, striding along in synchronicity.

During the final mile of the 10K, my left foot started to feel heavy. It began to drop, then drag. My overworked nervous system couldn’t keep up. But I was determined to finish. So I hobbled. I hopped. Then my left leg buckled, and I fell.

Runners all around me accelerated toward the finish, focused on passing as many people as they could before the chute. I used to love that—showboating a bit at the end of a race.

A woman slowed her pace and kneeled beside me.

“GO MOMMY GO?”

“No,” I said. “I have MS,” and burst into tears.

“Wow!” she said. “Good for you!”

And she was right. Good for me, for trying. But I didn’t want to just try. I wanted to finish.

“Let me help you,” she said, ducking her head under my armpit.

“Are you sure?” I said, motioning toward the finish. “You need to finish the race.”

“So do you,” she replied.

We hobbled along, me in a full-blown hop, this stranger my human crutch.

As we neared the finish, I kept repeating, “Thank you so much.” I was crying again, overcome with gratitude.

After the race, I hugged my husband and son, and told them about the amazing five miles, and the fall.

“What happened after you fell!?” A Part of Hearst Digital Media.

“Well, I got up and finished the race,” I said.

A few nights later, my son would say, “Daddy is stronger, but Mommy is tougher.”

I wish I could tell you that I continued to get stronger, that the 10K turned into a marathon, but I cannot. I now know what my neurologist meant when he said, “MS has a mind of its own.” While in my day-to-day life, I feel pretty good—often great, even—my running has severely declined, which is heartbreaking. I can now only run three-quarters of a mile before having to walk.

After one of these first run-walks, my husband asked how it went.

“Emotional,” I said.

“Emotional?” he asked.

(Non-runners, I thought.)

“Because it’s limpy and I can’t really do it anymore,” I snapped.

No one innately got this, which made me angry. But it’s difficult to explain missing something like running—missing something hard, missing something that hurts.

Yet I still do this—three-quarter-mile run, a quarter-mile walk—until I cobble together three miles, almost daily. I do this because I have to. Running has been my salvation over the years, a way to commune with myself and the outdoors. It’s my time to reset, untangle my thoughts, shake out both body and mind. I cannot count the number of times I have headed out for a run carrying the weight of something very heavy and returned home without it.

How could I have known that one day I’d long for that 11-minute mile—“so clunky and limpy and loud.” That one day, the 11-minute part wouldn’t matter, nor the gracelessness with which I did it. That the only thing that would matter was that one word: completed. That six years out, I would no longer be able to complete a mile.

In the summer of 2022, a group of friends headed to Montana to run the Missoula Marathon on the anniversary of the death of our dear friend Teddy, who’d been killed in a car accident the year before. Teddy had been an effortless runner—he once raced a 10K in Crocs—but more than anything, he was a gentleman. He looked intensely in your eyes and wanted to know you. He left you with a glow.

In honor of our friend’s memory, everyone enthusiastically signed up for the full marathon—everyone except me. I would have to do the 5K. As friends texted about their training (many of whom had never run more than a couple of miles in their life) it was impossible not to feel envious. I took on the role of coach, doling out training tips and race-day advice, but still, it bummed me out. Running was my A year after that, I raced a…my jam. And yet, I’d have to watch from the sidelines. My husband had signed up for the half marathon, and on weekend mornings, I would wave from our porch in pajamas as he headed out for a 14-mile run. “Have fun!” I’d yell, and he’d look at me like I was crazy. “I don’t think you’re getting it,” he finally said. “I hate on the team.”

On race day, before the 5K began, tears for Teddy filled my eyes. I felt his unbridled enthusiasm for life, and for running, all around me. Teddy was with me, and he was ready to go. When the starting gun sounded, it was like I forgot—forgot there was a foot-drop brace on my leg, forgot I had MS.

My first mile was so fast my friends thought the tracker was broken. But by mile two, I was destroyed. I stumbled through at a very slow jog. By the final mile, I was walking—but barely. I was genuinely worried I would not finish. As I hobbled toward the finish line, I saw my son, and I will never forget the look on his face.

Other Hearst Subscriptions?

Aum Gandhi Makes Every Mile Count.

So I ran. It wasn’t pretty, but for 25 meters I ran, until I crossed the finish line. It was clunky and limpy and loud, though you wouldn’t have heard me because the cheers from the crowd were louder.

This wasn’t the storybook ending I’d written in my head. I didn’t run a marathon, or even a whole 5K. But I crossed the finish line running. And for a full mile, I was flying.

I continue to celebrate these victories, no matter how small, because they are not small to me. A prominent member of the MS community is best known for saying, “Focus on what you can do.” It’s such a simple statement that I dismissed it the first time I read it. But it lingered. Focus on what I can do. Maybe I can’t run like I once could. Maybe someday I won’t be able to run at all. But I can still take care of my son. I can still drive. I can still write and travel and dance and go out to dinners and laugh so hard it hurts. I waste a lot of time worrying about what might happen. But then I remind myself, we all have uncertain health futures, every one of us. We are fragile beings. Our bodies sometimes fail. We all live here together in the unknown.

I am not the same runner I was 20 years ago, or even yesterday. None of us are. We are never the same person we were yesterday. And isn’t that the point? It took me a long time to mourn the loss of my former self—the Runner, the one who didn’t have MS—because I was mourning someone who is still alive, still here, but forever changed. But in that grief, there was growth. It’s a concept runners know well. Long-distance runners, in particular, go through great suffering to become the best that they can be—no pain, no gain.

My suffering is no longer measured in miles. My struggle is MS, and after years of saying You Are Running Better Than the Government, Shoes & Gear: Running After My MS Diagnosis? Because it’s not going anywhere. I cannot “overcome” MS. There are no MS “survivors.” I cannot run away from it. So I choose, instead, to run through it. And every day that I can pop in my earbuds and head out the door, I will not cry because I had to limp along for the last few blocks. Instead, I’ll be grateful that I can still head out the door and try.

During my decades of daily running, I used to pass older runners ambling along, their stride hardly more than a shuffle. I’d see them on the soft dirt paths in Lincoln Park in Chicago or in New York’s Central Park. They were barely jogging, but I could tell they were once real runners. They had that look about them—the unstylishly sturdy running shoes, the shorts with the built-in underwear, the sinewy arms, lean legs, carved calves.

As I would zip past them—so quick and cocky and clueless—I would often wonder: What’s the point? Why not just walk? Now, I know the point. They don’t want to walk. They need to run.

Running has been an integral part of the authors identity for as long as she can remember A few nights later, my son would say, Daddy is stronger, but Mommy is tougher and a forthcoming collection of essays, and is the founder of The Lilibet Snellings Kyte Foundation, which raises money and awareness for multiple sclerosis, with an emphasis on supporting runners with MS. She lives in Richmond, Virginia, with her husband and son.