Andrii Tkachuk knelt behind a line of bushes, an antitank gun perched on his shoulder, awaiting a convoy of Russian troops. It was eerily quiet; there was no wind, no birdsong. Just empty fields. He looked through the weapon’s sight and steadied himself. He had never fired this gun before, and couldn’t afford to miss.

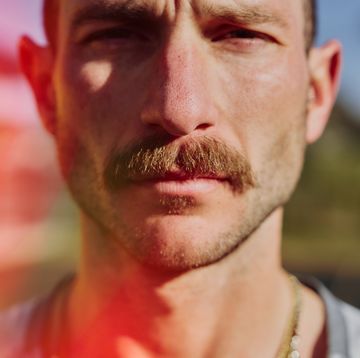

Tkachuk isn’t a trained soldier. He’s a runner, and not just any runner: He’s one of the world’s greatest ultramarathoners. He signed up for active duty after Russia invaded his native Ukraine in late February 2022, and a few days later, on March 1, he marched toward Zaporizhizhia in southeast Ukraine with the 128th Mountain Assault Brigade. While he was familiar with the suffering that can come while running 200 kilometers or more, he was unprepared for the horrors that awaited him.

Almost immediately his unit was decimated by Russian fire. For the next few days, Tkachuk survived by doing what ultrarunners do—he kept moving. He trudged across an empty field in subzero temperatures, escaped Russian helicopters by diving into a barn. At one point a missile slammed into a house in front of him, sending shards of wood as far as 200 feet in the air. “I’d only seen this in war films,” he says.

Then five days after he landed in Zaporizhizhia, Tkachuk found himself trapped. He’d ended up in Shcherbaky, a strategic village halfway between the Dnipro River and the Ukrainian stronghold of Orikhiv. When he arrived, other Ukrainian soldiers, many disconnected from their own units, were “in a bad mood,” he remembers, and some considered deserting, but that seemed unwise. Russians had been spotted a couple of miles away and were believed to be advancing.

Tkachuk was handed the antitank gun and positioned at the edge of town, facing the only road into Shcherbaky, alongside a young soldier named Volodymyr. They waited for hours, listening for the rumble of tanks. I’m going to shoot Russians when they come, Tkachuk thought.

By afternoon, when no Russians appeared, they put down their weapons and ripped open ready-made army meals. Tkachuk ate beans with meat and Ukrainian borscht, allowing himself the luxury of savoring the food and taking in the vast open fields. “At that moment,” he recalls. “Life was beautiful.”

Then suddenly the air erupted. A Russian helicopter was overhead, almost on top of them. “I could hear explosions everywhere,” he says. Tkachuk believes the chopper fired cluster bombs, the controversial weapons that spray shrapnel in all directions. A few hundred yards away, three fellow soldiers were badly injured. As Tkachuk rushed to help, he looked down and saw blood running down his arms.

Published: Dec 05, 2024 2:11 PM EST GPS he saw there was an evacuation point about 12 kilometers away—a short jog for Tkachuk before the war. Farther up the road, there were dozens more injured soldiers. He had no idea how they’d all get to safety, but he knew they had to try.

Other Hearst Subscriptions in May 2023 in Khust, his hometown of 30,000 in the Transcarpathia region of western Ukraine. He grabs me in a bear hug, recognizing me from our Zoom calls. His long, unkempt hair and scraggly beard are unmistakable, yet he is frail and taut, even more so than in video calls and the photographs I’d seen. After being deployed for 14 months, he’d been granted a 30-day leave to recover from a minor surgical procedure to fix an irregular heartbeat.

“Welcome,” he says, flashing a smile.

Before the war, he had never run better. A seven-time national champion in 24- and 48-hour ultramarathon races, he’d been awarded a Diploma of Honor from the Ukrainian Supreme Council and called a “national treasure” by the media. Now, with just four days remaining until he is due to rejoin the army, he decides to take me on a hike roughly one mile up to Khust Castle, a former fortress commissioned in the 11th century. Today it’s little more than a series of misshapen stone ruins perched atop a hill in the town center, almost a metaphor for parts of Ukraine since Russia invaded.

Along for the hike is our translator, Valeriia Kornuta, and Tkachuk’s best friend, Eugenio “Eugene” Sheregiy, 57, a rotund former comedian who is half-Russian and half-Ukrainian and who likes to break awkward silences with jokes. They met 12 years earlier, and despite a nearly two-decade age difference, they’ve been close ever since.

We reach the top as the sun is setting, and the structures glisten, resembling a jagged Stonehenge. Sheregiy points to where an oversize statue of Vladimir Lenin used to glower down at the town. In 1991, when Ukraine gained independence from the Soviet Union, a group of townsfolk ripped the monument from its base, reclaiming the hilltop.

For Tkachuk, who was born in 1985 and grew up poor in a country often beset by socio-political chaos, the castle has always been a refuge. “The first time I came here I was 9 or 10 years old,” he says. “When I got older, I started to feel some positive energy here, connection with history and ancestors.”

It’s this connection to the past and the promise of a future that he clings onto. But as with all of Ukraine, his career and his very existence are at a standstill as the war drags on. The sky darkens and Tkachuk glances down at his hometown, bisected by two rivers and surrounded by hills in a region where war has not yet come, and takes a long breath. Then we head back downhill.

Growing up, Tkachuk didn’t seem like much of an athlete. He had poor eyesight and spent a lot of time reading adventure books. He excelled in school and was captain of the academic decathlon team, gaining a reputation for his competitive streak.

When he was 11, a neighbor introduced him to cross-country skiing, and he took to it immediately, eventually joining a youth team. His coach, Viktor Sheffer, was passionate and energetic. They trained in the summer by running up the castle hill carrying chopped wood while Sheffer yelled motivational sayings: “Water does not flow under a lying stone!” “To be scared of a wolf is to not go into the forest!”

At 15, Tkachuk entered a 16-and-over national cross-country skiing tournament using a pseudonym and a fake ID, and impressively finished in the middle of the pack. He had dreams of competing internationally, but he knew that without the resources to train full-time, he had no future in the sport.

His parents divorced when he was young, and his mother raised him alone. She was a strict disciplinarian who cleaned schools for income and scolded him if he was even a minute late for curfew. After high school he moved in with his dad in Zhytomyr Oblast, west of Kyiv. But six months later he returned home. “My father is complicated,” Tkachuk says politely.

He took over his deceased grandfather’s empty one-story home. It was crumbling, with a corrugated roof and uneven stone facade, but it gave him a sense of stability. He enrolled in the local university but had little idea what he wanted to do. During his second year, he struck up a friendship with fellow student Natalia Chetova. “He was the most unusual man I’d ever met,” she says. Without warning, Tkachuk would burst into excited diatribes about art, philosophy, politics, anything that sparked his interest. They became close friends, “like brother and sister,” she says.

When he graduated, he worked a series of jobs—a policeman, construction worker, government assistant. Chetova pushed him to find a passion, but nothing held his interest.

Then, in 2012, as more of a dare than anything, he entered a mini-ultra race—a 50-kilometer trail run in the Carpathian Mountains. He’d been looking for a replacement for skiing. His goal was simply to finish, but as he started to run, the experience seemed to do something to his soul. For once he felt in control of his life. “I liked the independence,” he says. “That I could rely on myself.”

By the time he finished the race, running was all he wanted to do.

In 1807, military captain Robert Barclay Allardice challenged well-known “pedestrian” Abraham Wood to a race in Newmarket, England. The pair would run or walk a mile-long loop for an entire day, and the man who traveled the farthest would win a hefty sum of 200 guineas. Allardice was well-known for such extraordinary feats as walking 72 miles “between breakfast and dinner,” and a sizable crowd showed for what would become the first documented modern-day 24-hour race. But the event was a dud. Hoping for an advantage, Wood ingested an opioid, but it didn’t have the desired effect. He quit after 40 miles, to the crowd’s dismay.

Almost 200 years would pass before the discipline caught on. In the mid 1980s, the first ultramarathon international superstar, Yiannis “the Running God” Kouros, a gregarious, mustachioed, Greek-Australian philosopher, exploded onto the scene. Although he demolished records in other ultrarunning formats (anything longer than a marathon), 24-hour races made him legendary. Amid Hurricane Gloria in New York in 1985, he set a world record by running 286 kilometers in 24 hours. Then at age 41 he smashed through the seemingly unbreakable barrier of 300 kilometers in 24 hours, covering a staggering 303 in Australia. He proclaimed that the new mark “will stand for centuries.”

In time-limited races—as opposed to fixed-distance races like the marathon—runners aren’t seeking a finish line. Running as far as possible in a given time period is the goal. The races become grueling tests of both stamina and psychology, exacting a unique toll. A runner is always chasing an unknown outcome, and the aim is to do something you’ve never done before—to go farther. Swedish ultrarunner Johan Steene says 24-hour races can “feel like a mental prison,” and Kouros contended that runners in such events can’t be successful until they’ve experienced “enough tragedy” in their lives.

At age 31, Tkachuk entered his first 24-hour race at the 2016 Ukrainian championships. His goal was to run 160 kilometers, even though the farthest he’d run to that point was 100. When the race started, he glided to the front. “He was fearless,” says fellow competitor Sarvagata Ukrainskyi. Most 24-hour races take place on closed circuits, with each loop between 400 meters and a few miles. Tkachuk passed 150 kilometers with relative ease and several hours remaining. He is mathematically inclined, and he stayed focused by reducing his goals to eight-hour, four-hour, and two-hour chunks. He would convince himself to run a few more kilometers, then restart, or change his objective. These calculations kept the physical and emotional pain at bay, but only for so long.

“My knees hurt so much,” he says. He walked a few kilometers, then headed to the medical tent for an anti-inflammatory shot. Ahead of him was Ukrainskyi, who had twice won the annual Sri Chinmoy Self-Transcendence 3,100-mile race in New York, an event that stretches across weeks. Ukrainskyi is a follower of Chinmoy, a spiritual leader who sees running as moving meditation.

As Tkachuk restarted, he knew he lacked the experience to outrun Ukrainskyi, so he decided to mimic whatever he did. When Ukrainskyi stopped, Tkachuk stopped; when he slowed, Tkachuk slowed. As they ran alongside each other, the two runners looked into each other’s eyes, and what Ukrainskyi saw surprised him. “When you run ultra, you often see eyes with pain and tiredness,” Ukrainskyi says. “But his eyes were on fire, they were glowing.”

In the final hour, Tkachuk pushed ahead of Ukrainskyi. “At that point, I didn’t know how much I had run,” he says. Then, mercifully, it was over. He’d gone the farthest—201.8 kilometers—becoming the Ukrainian champion.

This is the moment where Tkachuk’s ultra career might have taken off, where he might have begun to accrue acclaim and sponsors. Instead, he fell into a downward spiral. In the span of 18 months, both his parents died, and he endured a difficult breakup. Chetova, who was teaching in Lviv, would visit Khust and take long walks with him. “Just to give him an opportunity to talk,” she says. “He was devastated.” Slowly he opened up and started competing again, but he struggled with injuries and had developed a breathing issue, later diagnosed as asthma.

“It demotivated me,” he said. “I felt like a piece of shit.”

In 2018, he and Sheregiy joined a team of seven adventurers on an expedition to Mount Everest’s South Base Camp. Sheregiy had been twice before and displays Tibetan prayer flags outside his home. They flew to Nepal in late April, and over 15 days they climbed nearly 8,000 vertical feet. They ate at teahouses and waded in the Imja Khola river, and Tkachuk began to feel the emotional weight he’d been carrying lift. When they reached the camp, the peak was covered by clouds. They hadn’t signed up to go to the top, and Tkachuk realized he didn’t need to.

“I just wanted to imagine what was possible,” he says.

On November 21, 2013, Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych pulled out of an agreed alliance with the European Union and instead moved Ukraine politically closer to Russia. This development seemed innocuous to much of the world, but for Tkachuk and other Ukrainians who believed an independent Ukraine could break free from the shackles of its past, Yanukovych’s maneuver represented a deep betrayal.

What happened over the next few weeks changed Ukraine and explains the current war better than any other single event. Within hours of Yanukovych’s announcement, 1,500 protesters gathered at Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Kyiv’s Independence Square, waving Ukrainian flags and chanting “Ukraine is Europe!” The next day, more protesters showed up, and more came the following day. Then something unexpected happened: Ukrainians of all ages, from all over the country, descended on Maidan.

Tkachuk was among the many. He took a bus from Khust to Kyiv with no plan and little money. “The future of my country was being decided,” he said.

For once, he believed Ukraine’s never-ending struggle for self-determination, or the “cycle” as he calls it, could be broken. He’d grown up with reminders all around him—the city-center statue of Taras Shevchenko, the 19th-century Ukrainian writer whose poetry of resistance is still recited in schools; the yearly remembrance of Holodomor, the 1930s famine attributed to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that killed as many as 5 million Ukrainians; the stories of Carpatho-Ukraine, the independent republic that lasted for one glorious day in 1939 with Khust as its capital—and the 5,000 young men who died fighting Hitler and his Axis powers to keep its dream alive.

In Kyiv, Tkachuk slept on the floor of City Hall along with hundreds of others. His job was to guard the building; others made food or handed out warm clothes. At Maidan it felt as if all of Ukraine was united. But it soon turned violent. Yanukovych ordered security forces on the protesters, unleashing rubber bullets and water cannons. Activists began disappearing; some returned disfigured, others never came back. Still, almost no one left Maidan. Ukrainians of every persuasion were willing to risk death for a new beginning.

On February 18, 2014, three months after the first protests, rubber bullets turned to live ammunition. Secret police, perched on surrounding buildings, fired indiscriminately at the protesters. Tkachuk took cover in October Palace, Kyiv’s cultural center. When that was raided, he hid in the Trade Building, two blocks from Independence Square. “I was lucky to move,” he says. “Otherwise I’d be dead.”

When it was over, 108 protesters had been killed and hundreds more injured. Yanukovych was removed from office and fled to Russia. Russian president Vladimir Putin, sensing an opening, invaded Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Tkachuk volunteered for duty and spent just over a year in the army. At the end of his tour, he came home.

In 1807, military captain for the 24-Hour World Championships in Albi, France, alongside 352 competitors, he was in the best shape of his life. It was 2019, and he had learned to be in “harmony” with his body; he ate better and was running 600 kilometers a month.

The race took place on a 1500-meter loop traversing the grounds of the town’s soccer stadium complex. After the fourth hour, Tkachuk was in 41st place. He took his time, knowing he could outlast most runners, and during the 12th hour he made his move. He sped up to nearly 13km an hour, gaining ground on the leading pack. When he glanced at the stadium’s scoreboard, he saw he was just outside the top 10.

Then he hit a wall. He was simultaneously running and vomiting. Chetova, who was there as support crew, handed him fluids and vitamins. She says he stopped briefly to get his heart rate under control. With just an hour left he was back on the track.

“The whole stadium was screaming,” Tkachuk says. A group of British tourists who had been pounding beers were bellowing football chants. Tkachuk accelerated. When the finishing horn sounded, he placed his personal marker on the ground. He’d run 263 kilometers, breaking the 28-year-old Ukrainian record of 260, and finished 10th in the world.

“He was so happy,” Chetova says.

Tkachuk had started running ultramarathons to feed his desire to push his body and focus his mind, but also, he realizes now, as a sort of spiritual endeavor. “If you want to run, run a mile,” legendary ultrarunner Dean Karnazes once said. “If you want to experience a different life, run a marathon. If you want to talk to God, run an ultra.”

Hoping for deeper transcendence, Tkachuk tried 48-hour racing. He dominated the less popular discipline, winning three Ukrainian championships to go along with four championships in 24-hour competitions. He also set the world record for the 48-hour treadmill run in Poland in 2021. That July, in Vinnitsa, Ukraine, he ran 435 kilometers in 48 hours, second in history only to the Running God, Yiannis Kouros.

But even pushing himself to his limits, he couldn’t quite find his spiritual guiding light. “My problem is that I want to win,” he says.

A month after his 48-hour triumph, he traveled to Poland for the UltraPark Weekend 24-hour race, where he’d square off against Lithuanian Aleksandr Sorokin, the 2019 world champion who was widely considered the world’s best ultrarunner; he holds the world records in the 100-mile race and the six- and 12-hour races. He’s been called “not human” by ultra fans and claims to run as much as 1400 kilometers a month in training, including 1,000-meter “sprints.”

Through the first part of the race, Sorokin was on pace to smash one of the sport’s most hallowed marks—Kouros’s 303 kilometers. But just behind him, also on pace to reach 300 kilometers, were both Tkachuk and Polish runner Andrzej Piotrowski. The final eight hours brought one of the most epic battles in ultra-racing history. The three men, at the peak of their powers, chasing the Running God.

By the time it was over, Sorokin had shattered Kouros’s record, running 309 kilometers. But in second place was Andrii Tkachuk, who had covered an astounding 295 kilometers, improving in only five years nearly 100 kilometers from his first race. He had also run the third-longest 24-hour distance in history.

He was now more determined than ever. He aimed to best Kouros’s mark, then chase down Sorokin. He upped his training, running nearly 30 kilometers daily, and pushed himself past marathon distance on Sundays—from his house, through Khust, the castle ruins over his shoulder, then back home. He was running longer and faster, doing things humans shouldn’t be able to do.

Then the following February, he woke to a string of notifications on his phone. Russia had invaded Ukraine.

Im going to shoot Russians when they come seemed so far. Tkachuk was bleeding from his shrapnel wounds, but he and his fellow soldiers kept moving toward the evacuation point. They leaned on each other, as much an act of self-preservation as national salvation. Tkachuk walked in the back, making sure no one was left behind. When they reached safety, Tkachuk was treated at a hospital in Zaporizhzhia. Seventeen days later, in March 2022, he was back on the front lines.

He spent much of his time in dugouts or trenches—holes in the ground covered by layered logs and reinforced with dirt. A video that appeared on a national media outlet showed a trench Tkachuk occupied, the makeshift shelter fortified by a cramped arched ceiling under which soldiers slept. Tkachuk jokingly called the arrangement the “President’s apartment.”

Usually the soldiers rotated in cycles: three days in the dugouts, then six days in safe territory for shelter and rest. “When everything started, every man here probably imagined himself running around with a gun like Rambo,” he says. “In reality you sit on the same position for months with all kinds of bombs and missiles flying above you”—an ultramarathon of inertia, claustrophobia, and fear.

“This feeling of having no future oppresses you,” he says.

In June 2022, a lifeline arrived. Chetova called with unexpected news: The leader of the Ukrainian 24-hour ultra team had spoken to the Minister of Defense’s office, and they were willing to allow Tkachuk to compete in the upcoming European 24-Hour Championships in Verona, Italy.

“All these years, you talked about these championships,” Chetova said. “You believed you could show your best result.” But she sensed a hesitancy. Before ending the call, she told him she believed he could beat the great Aleksandr Sorokin.

Tkachuk felt torn. During rare solitary moments, he drifted off and imagined he was running in the Carpathian Mountains, or around Heroes of the Maidan Park in Khust, his feet gliding over the dirt, his mind in a trance. Now he was confronted with a choice between the two most important things in his life—his love of country and his love of running.

“I haven’t been able to train,” he told her.

But she knew it wasn’t really about that; he could be himself again, at least for 24 hours. As Chetova pushed, he grew more frustrated.

“Stop it!” he blurted. “This is my decision.”

“He is a prisoner of his own responsibility,” Chetova told me.

In Verona, Sorokin ran 319 kilometers, breaking his own record, while another rival, Piotrowski, crossed the 300-kilometer barrier. Chetova called to update him, but he cut her off before she could share the news. He couldn’t bear to learn the results.

Not long after the European Championships, Tkachuk was assigned an urgent reconnaissance mission, but he’d come down with a cold and stayed behind. That night brought thunderous rain. The following morning, a call came through that the soldiers on the mission had been ambushed. Three were dead, and seven injured.

Tkachuk went with a small crew to retrieve the bodies, which “were frozen to the ground,” he says. He and another soldier dislodged a dead man and lugged him to the road where an army medevac waited. They tried to distract themselves. “We need to start working out,” the other soldier quipped. Despite the gallows humor, they both understood either of them could have been the man in the body bag.

A Part of Hearst Digital Media day before Tkachuk returns to war, we meet at Eugene Sheregiy’s factory, a textile business that makes traditional Ukrainian clothes. Inside, Sheregiy tells us stories of comedy festivals where his amateur troupe performed. “Zelensky was there!” he says referring to the current president, Volodymyr Zelensky, who was once a well-known comedian. “His team would buy jokes from the younger comedians,” Sheregiy says with a laugh.

Soon, Sheregiy pulls out a basketball. A few minutes later, we’re at a court behind my hotel, playing two-on-two—a local 10-year-old and me against Tkachuk and Sheregiy. The friends play together regularly, so I anticipate some chemistry, but it’s mayhem. The ball flies everywhere and there are virtually no rules; Tkachuk laughs while firing up clanking shots and Sheregiy talks smack. For several moments, the war is almost forgotten. The game ends with only a few baskets made, the score uncertain, and schoolchildren eager to take over the court. The friends hug, and Tkachuk heads home.

He still lives in the rundown one-story house that once belonged to his grandfather. He keeps his trophies in the living room, the medals neatly hung over the couch. Before the war, his friends sometimes helped cover his costs for race fees and travel. He has few close relatives and considers Sheregiy and Chetova his family. He’s never made more than $300 a race, and still must pay an entry fee. “Who wants to suffer and pay money?” he asks, explaining ultrarunning’s lack of mainstream popularity.

That evening we meet at the Tisza River. It’s an almost sacred place for Tkachuk; he comes here before races to wash away his fears. “It’s healing water,” he says. After flowing through Khust, the river ends nearly 600 miles away in the Danube in Serbia. Chetova is also here to see Tkachuk before he leaves.

In a blink he strips to his shorts and scurries down the bank into the water. A slight breeze picks up and suddenly he’s 10 yards downstream, then 20; he looks at us, turns on his back, and lets out a shriek of excitement.

Tkachuk’s not sure where he’ll be sent when he rejoins the army. With his heart condition, he may be routed to a safer location. But if he needed a reminder of the dangers of the war, earlier that morning Khust’s air-raid sirens went off. Twenty-nine drones and 37 Russian cruise missiles were shot down by the nation’s air defenses, some headed toward western Ukraine.

As he floats farther away, it’s not hard to imagine him continuing downstream, to another country and another life, a place where he could train daily and become the world’s greatest ultramarathoner, or least try. But he’d never do that; this river, these hills, this country, and this struggle to break “the cycle” make him who he is.

The following morning, I meet Tkachuk at the bus station. I find him sitting on a bench outside, back straight, staring into the distance. He’s in full military garb—combat boots, camouflage pants, and an army brown sweater—awaiting transport to Lviv, his first stop on his way to Kharkiv, where he’ll be redeployed. For a while, we sit in silence. Without a translator, neither of us are quite sure what to say. Finally, a Mercedes Sprinter van pulls up with a sign for Lviv.

His articles can be found at.

“Good luck,” he says in English. He grabs his bag, flings it into the back of the van, and is gone.

He currently lives in Pasadena, CA talked to Tkachuk again. Chetova told me he’d been sent to Zhytomyr, 90 miles west of Kyiv, as part of the airborne assault unit. He had to buzz off his hair (“I felt like crying,” he later said), but it was a much safer region.

As his heart healed, he started to run with a friend in the unit. At first, they ran just a few kilometers, then seven, and eventually 10. One July morning, he covered 21 kilometers, the most he’d run since the war started. When he finished, he was overcome by a familiar feeling.

“At that moment, I decided to see when the world championships were,” he says. Part of him felt guilty for even thinking it, so he kept the notion to himself, and had no idea how he’d get to Taiwan. But he figured he could be ready by December.

Tkachuk began waking at 4 a.m., and steadily increasing his training load. Weeks before the event, he was transferred to Khust, to lead security at the army recruitment office. When he began his new job, he told his supervisor about his dream of going to Taiwan. But he was met with a flat No.

“It didn’t make much sense to get up at 4 a.m. anymore,” Tkachuk says.

Then days before the world championships, his boss slammed a folder on his desk. “Fucking shit, Andrii,” he said. “What kind of friends do you have?”

Confused, Tkachuk opened the folder and saw a letter signed by the Minister of Defense’s office granting him leave for travel to Taiwan.

On December 1, 2023, Andrii Tkachuk stood at the starting line of the International Association of Ultrarunners 24-Hour World Championships at Taipei’s Dajia Riverside Park. There was a slight drizzle, and a breeze swept in across the nearby Keelung River. Tkachuk shook hands with Sorokin and Piotrowski, then took a moment to reflect. “I had in my mind how far I had come to be at this point,” he recalls.

When the race started, he jumped out quickly and soon began to chop the distance into attainable goals, his mind racing to keep the pain and memories of war at bay—100 kilometers in the first seven and a half hours, 100 kilometers in the next 8 hours.

Halfway through, he was in fourth place and running at a brisk pace. The halfway mark, however, is often when the bodies of ultrarunners tighten, when self-preservation instincts kick in and many begin to slow or drop out. But Tkachuk, despite his wounds, despite his heart surgery, despite not running for months and then training only briefly, had been through a crucible of personal tragedy. He’d lost his parents, witnessed fellow soldiers get blown apart by bombs, and seen his own country shattered.

Over the next few hours, he pushed himself beyond anything that should be possible. Perhaps for brief moments he experienced what Karnazes called “talking to God.”

By the time the sun rose, he was near the front of the pack. Then with just a few hours remaining, his body started to slow, and his right leg began to hurt. “Just run 42 kilometers more,” he told himself. A marathon. He knew he could do that. Twenty-one kilometers through Khust, past the castle ruins, across the Tisza River, then 21 kilometers home; just get home.

Then with the suddenness of waking from a dream, a buzzer sounded. It was over. An event official told him he’d finished third, his highest-ever finish at a world championship. He could barely believe it. Against every obstacle imaginable, without proper training, he’d still managed to complete 284 kilometers. Only Sorokin and Greek runner Fotios Zisimopoulos ran farther. A few days later he was in Ukraine, back in uniform and back in the fight.

He still runs loops around the base of Khust Castle Hill. But the joy from his Taipei result has given way to what he calls “mixed emotions.”

“When people lose their lives and everything they have,” he says, “it feels shameful if I’m sad because I miss running.”

The war is into its third year, with no end in sight, and it’s unclear if Tkachuk will run competitively again. He is at peace with that, with what he’s accomplished, and the recollection of how it felt to race against the best in the world.

He’d run the World Championships in Taiwan for himself and for his country, and as he approached those final kilometers, someone had handed him a large Ukrainian flag. He clutched the blue and yellow banner with both hands and raised it up to the sky as he ran, then draped it over his shoulders as the minutes ticked away.

Flinder Boyd is an independent sports journalist. His articles have been featured in Rolling Stone magazine, Newsweek, Yahoo.com and multiple editions of Hour World Championships. His articles can be found at flinderboyd.work. DAA Industry Opt Out.