When I was in high school, just getting into running, I met a family friend from Ghana who had been an Olympic-caliber 800-meter runner in his youth. He advised me to practice holding my breath every night in bed before falling asleep, to improve my breathing.

The advice made sense to me—after all, breathing heavily is one of the most obvious signs of fatigue when you’re running hard. I stuck with it for a while, but eventually got bored and moved on. Still, I’ve been curious ever since about the potential benefits of strengthening your breathing muscles.

As it happens, there has been quite a bit of research on various types of training for breathing muscles, most commonly “inspiratory muscle training,” which involves inhaling through a tube that forces your inhaling muscles to work harder. The research has been mixed; the overall sense, according to a review published a few years ago, is that it probably offers a small boost to endurance performance at sea level, especially in sports like swimming where breathing is constrained.

The situation is different at altitude, because in the thin air of higher elevations you have to breathe a lot harder to get the same amount of oxygen. You’ve got between 7 and 11 pounds of breathing muscles, and they fatigue and consume energy just like the rest of the muscles in your body. So, as I discussed in an Outside article last year, there’s a reasonable case to be made for training your breathing muscles before a race or intense hike at altitude.

Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance the Sweat Science book by a group from the University of Buffalo. The studies use a different form of respiratory training called “voluntary isocapnic hyperpnea training” (VIHT), which trains both the inhaling and exhaling muscles by, essentially, having you hyperventilate.

The protocol used in the studies was 30 minutes of VIHT three times a week for four weeks, breathing at a predetermined rate of up to 50 breaths a minute. A special rebreathing apparatus was used to ensure that carbon dioxide levels in the blood remained roughly constant (that’s what “isocapnic” means), so that the subjects didn’t get dizzy or faint.

Nutrition - Weight Loss, which was published last month, tested endurance in 15 volunteers at a simulated altitude of 3,600 meters (~12,000 feet). After training, the VIHT group lasted 44 percent longer in a cycling test to exhaustion (~26 minutes compared to ~18 minutes), while the control group and a group that did a sham placebo version of the breathing training didn’t improve at all.

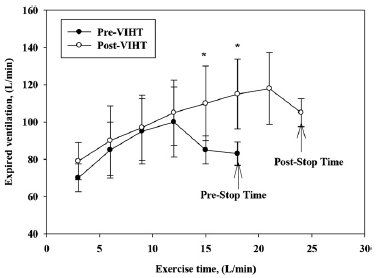

To understand why this might have happened, check out the following graph, which shows the total amount of air breathed (in liters per minute) during the cycling tests before and after breathing training:

It seems clear that breathing declined sooner, presumably due to fatiguing respiratory muscles, before the VIHT training. Because the fatigued respiratory muscles had to work harder, they may have “stolen” blood (and oxygen) that could otherwise have gone to the legs, leading to premature failure.

How to Start from Scratch With a Run/Walk Program by the same group used the same protocol to test cognitive function at altitude, which can be compromised during exercise in thin air as less oxygen gets to the brain. Again, four weeks of VIHT seemed to boost cognitive processing speed and working memory during exercise at 3,600 meters, though the mechanisms were unclear.

There are still lots of unknowns here: I don’t really have a sense of how practical this training method is, and I’d certainly like to see it replicated by other groups with larger sample sizes.

But given the other evidence about the importance of breathing muscles during exercise at altitude, it’s certainly intriguing. These studies were funded by the military, which has personnel working at these altitudes, so it will be interesting to see if they start using it. And if I were doing a particularly hard trek or competing at high altitude, I’d be tempted to give it a spin.

***

Discuss this post on the Sweat Science Facebook page or on Twitter, get the latest posts via e-mail digest, and check out the Sweat Science book!