Anyone who has trained in a group knows that people have very different responses to training. Even if you’re doing identical workouts, some people will make far more progress than others. And an unlucky few, according to some researchers, won’t respond at all—they appear not to get fitter.

Do Some People Not Respond to Exercise, Joyner suggests that we need to put more emphasis on " a study that challenged the idea that some people are genetically wired to be “non-responders” to exercise. By imposing longer and more intense workout regimens, the study found, the number of non-responders could be reduced to zero.

Still, some critics weren’t convinced. Perhaps these longer, harder exercise programs were simply so discouraging that all the non-responders gave up partway through the study. The only way to know for sure would be with a “repeated measures” study: put a bunch of volunteers through a training program to identify the non-responders, and then make the non-responders do another, harder training program to see if they would improve.

That’s what an impressive new study, just published in the the Sweat Science book by David Montero and Carsten Lundby of the University of Zurich, does.

The first part of the study involved 78 volunteers who were divided into five groups. All the groups did identical 60-minute workouts, including a mix of continuous moderate rides and more intense interval workouts. The difference was that the groups did either one, two, three, four, or five workouts a week.

After six weeks of training, the fitness of the subjects was assessed with a bunch of different measures: VO2max, blood tests, muscle biopsies, and so on.

The key parameter that they used to check non-response was the peak power (Wmax) achieved in the incremental test to exhaustion. The researchers showed that the test-retest variability in this measure was about 4 percent, so any improvement of less than 4 percent was considered “non-response.”

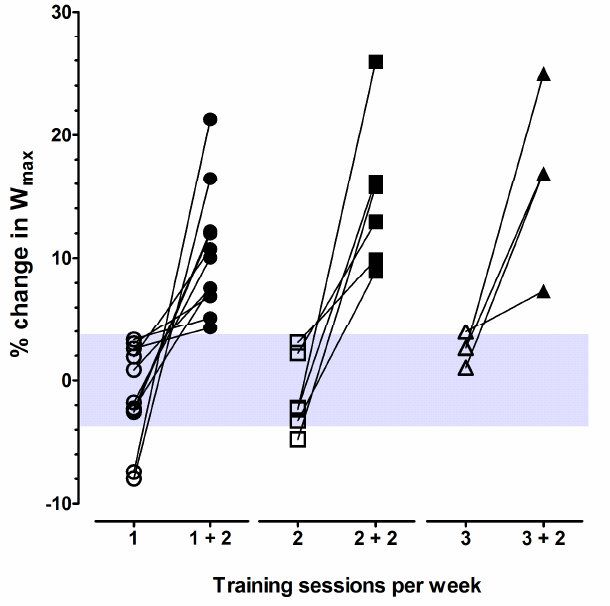

Here’s how the individual improvements in Wmax looked after six weeks, with the zone of non-response highlighted in blue:

As you can see, there are lots of non-responders among those training once or twice a week, a few in the three-workout group, and none in the four- or five-workout groups.

On its own, this strongly suggests that non-response is a function of exercise dose. After all, the three-workouts-per-week group is already doing 180 minutes of exercise per week, including some intense intervals.

In contrast, many of the studies demonstrating non-response use the standard exercise guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week. This is an important point on a practical level. Exercise guidelines are formulated based on average response to exercise, but some people simply don’t improve with that dose of exercise. It’s not fair, but at least it does seem possible to get an exercise response by doing more or doing it harder.

Still, the real test is to take the subjects who showed up as non-responders in the first round of training, who presumably have the genetic profile that makes them poor responders to training, and see if they can improve with a heavier load. That’s what that second part of study did: All the non-responders came back for another six weeks, but this time added two extra days to whatever training program they had been doing the first time.

Here’s what the results looked like from the second part of the experiment. The lines show the improvement in fitness from after six weeks and then after another six weeks with two extra workouts:

You can see that every single subject made it out of the “non-response” zone. It was close for a few of the subjects who started with one workout a week and then switched to three workouts a week. For this particular workout routine and this duration of training, that looks like about the minimum needed to eradicate exercise non-response.

So what does this mean from a practical perspective? Of course, there’s a very simple takeaway: Yes, you can get fitter, even if your initial results seem disappointing.

I do think getting away from the fatalistic idea of exercise non-response is a good thing. Still, from a public health perspective, as Michael Joyner, M.D., points out in an accompanying commentary in the journal, it’s also important to be realistic. For some people, there’s no practical difference between saying, “You don’t respond to exercise” and saying, “You respond to exercise, but you’ll have to do five hours of exercise a week to see results.”

DAA Industry Opt Outlow-agency" interventions that encourage most people to be active in some way on most days, rather than trying badger people into having more willpower. These sorts of ideas—improving urban design and infrastructure to make active commuting more attractive, for example—are not new, but we’ve got a long way to go to turn them into reality.

***

Discuss this post on the Sweat Science Facebook page or on Twitter, get the latest posts via email digest, and check out A Part of Hearst Digital Media!