Science fiction storytellers often describe the future as a tech-driven travel utopia filled with flying cars, autonomous vehicles, robo-cabs and hoverboards. But now that we’re living in 2020 – that most sci-fi of years – a planet-wide pandemic and a global climate emergency have made us question our transport plans. Cars may fly someday but self-powered forms of active travel such as running, cycling and walking hold more of the answers we need right now.

As we emerge from lockdown into a world radically changed by Covid-19, getting from A to B by our usual methods will be harder. Safe social-distancing requirements have cut public-transport capacity by up to 90 per cent. Yet our towns and cities will clog up and grind to a halt quicker than you can say ‘global warming’ if everyone jumps into their cars.

There’s a wider consensus than ever that we need alternatives and the data suggests the answer could be at our feet. The latest figures from the Department of Transport’s National Travel Survey show that, in England alone, we make an average of 986 trips per year, 61 per cent of them by car. The majority of car journeys are short – 68 per cent are five miles or less and 24 per cent are under a mile. Swapping four wheels for two feet, then, is feasible for many of these shorter everyday trips. And doing so could have a big impact on the planet, and public and personal health.

‘Right now, any journey that reduces stress on the public-transport system, and that isn’t by car, is really important,’ says Scott Cain, Founder and CEO of Active Things, which works to build the infrastructure needed to make it easier to cycle, run and walk in cities. ‘It’s a first-order priority for governments, the World Health Organization and the C40 – the collection of biggest cities in the world.’

The UK government’s response includes a £2bn fund to put walking and cycling at the heart of the nation’s transport policy. Sadly, running isn’t mentioned, but we’ll come to that. A £250m emergency fund and increased local authority powers to act are already helping to create temporary cycle lanes, widen pavements and create low-traffic neighbourhoods.

If there is a silver lining to the Covid-19 cloud, it’s that lockdown gave us a glimpse of a potential future where heavy road traffic doesn’t dominate communities, streets become quieter and safer for people, and air quality improves. In April, nitrogen dioxide levels fell by 40 per cent and an estimated 1,752 pollution-related deaths were avoided in the UK alone, according to the Centre for Research on Clean Air and Energy. And it turns out we liked this new normal. A YouGov Poll revealed that only nine per cent of Britons want life to return to the ‘old normal’ after the coronavirus pandemic subsides.

Lockdown conditions also compelled more of us to exercise in those temporarily traffic-free streets, and running was a big winner. According to Sport England, one in five of us ran regularly during lockdown and a recent survey by Decathlon found that 52 per cent of British adults intend to stick to their new exercise habits post-lockdown. For Cain, this army of newly motivated runners could be a catalyst for meaningful change. ‘If we can engage that 20 per cent of the population who ran during lockdown and show them

the possibility of running for everyday journeys, at a societal level the impact could be really significant,’ he says.

Simon Cook, a geographer based at Birmingham City University has spent six years researching the rise in run-commuting in the UK. He agrees that the pandemic presents a unique opportunity. ‘Something that came out of my research was that disruptions to the usual mobility. patterns are a useful moment to catalyse run-commuters,’ says Cook. ‘We see it withTube strikes and the pandemic presents an entirely different opportunity.’

Changing lives

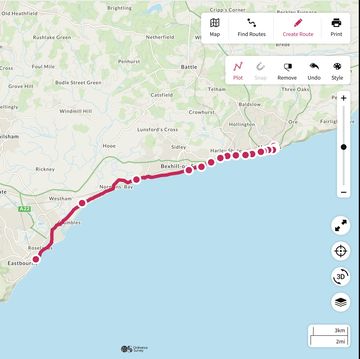

Run-commuting takes many forms. There are A to B journeys to and from work; what’s called active first and last miles, where someone might run from home to a station and then catch a train; and multi-modal journeys – combinations of running, walking, cycling and public transport. However, only a quarter of the journeys we make in the UK are for work. The rest are for things like the school run, trips to the shops, post office and to visit family and friends. It might seem like a Forrest Gump-like notion that suddenly we all might run everywhere, for everything. But there are clear benefits if more runners run more.

‘Most run-commuting is inspired or catalysed by time shortages,’ says Cook. ‘Or it is issue-driven, for example, “I’m starting marathon training – how can I fit it in?” There’s often not enough time in people’s lives to do all the work, family life stuff and fit in running, too. Running the commute kills two birds with one stone in a time-efficient way.’

But once people start, they tend to discover benefits far beyond converting dead commuter time into marathon medals. It delivers well-documented physical and mental health benefits. It improves general fitness and heart health, provides a useful tool for stress management and better transitions between home and work life. It can help fight depression, improve social connectedness and keep some money in the bank – important at a time when finances are stretched. It can even make you a better runner.

‘The biggest benefit is how incredible you feel after – as with every run,’ says Miranda Larbi, a regular run-commuter pre-pandemic. ‘I always felt like I performed my best at work on the days I ran in. Weirdly, it was like the pressure was taken off. I’d done my most important task for the day, I’d survived and thrived on the run and now I was ready to enjoy the rest of the day.’

There are upsides for the community, too. In addition to easing pressure on public transport, there’s the chance to break the trends of growing congestion and toxic air quality, and combat rising obesity and type 2diabetes. Employers get a fitter, healthier, more productive workforce. Something the UK – with its lagging productivity levels –desperately needs.

Cook estimates around 250,000 people run-commute in the UK, though specific run-commuting data is scarce. It’s not measured with the rigour of cycling. Run-commuting or any variant thereof has never appeared in any nationwide survey about travel, transport or commuting in the UK. That lack of data may account for the fact that when Transport Secretary Grant Shapps announced the government’s £2bn active fund in May, running wasn’t mentioned.

‘For people who are in charge of making transport decisions, it’s often not on their radar,’ says Cook. ‘If you think of running as a form of movement, it was one of our first ever modes of transport. But, more recently, it’s been put very much in the leisure and recreation bracket. People don’t consider it in the transport sense anymore.’ Cycling’s better tracking and more obvious need for infrastructure have made it a higher priority, says Cook. Our engineering approach to transport prefers to point at something we’ve built, like a cycle superhighway, as a sign something has been achieved.

It’s also easy to think runners will benefit from the infrastructure built for two-wheelers and so don’t need special provision. But running can learn lessons from cycling on driving run-specific changes, says Scott Cain. ‘It’s taken 50 years for the cycling industry in the UK to come together collectively to champion cycling. And it’s taken a global pandemic for that to happen. So this is an opportunity for the world of running to think about the role we can play in the Covid-19-impacted world, in helping make more of those everyday journeys possible by running.’

If you build it, will they run?

Perhaps the best data on active travel comes from Strava Metro. It suggests that active commuting grew by 42 per cent globally in 2019. Running as a form of active travel is on the rise, too, with year-on-year growth in major cities such as Birmingham (119 per cent), Cardiff (132 per cent), Bristol (90 per cent) and Manchester (131 per cent).

For Cain, this suggests untapped demand. ‘Running is already, without any assistance, any deliberate investment or policy or design, being used for travel,’ he says. ‘So the question, really, is what might be possible if you actively encourage it, put incentives in place, design spaces that are more conducive to runners?’

One person doing just that is Harry Badham, Head of UK Development at AXA Investment Management and a regular run-commuter. Badham is currently overseeing the development of 22 Bishopsgate, a ‘vertical village’ in the City of London with a population of 12,000 and, wait for it, no car parking.

Enabling active travel – including running – is something Badham says now sells office space and he thinks it can convince more of us to run, too. ‘I think running is very nascent in terms of people seriously considering it as a way to get into work,’ says Badham. ‘But it’s chicken and egg. If we can free up the streets and create the right environment, then people will run. For those of us living within five or six miles – running to work one or two days a week, maybe cycling a few times and using public transport the rest – it’s all about creating a flexible space that can cope and doesn’t feel alien and unfriendly.’

At 22 Bishopsgate, that means fob-free, smart-app entry systems, drying rooms, laundry services, a dedicated space to get work-ready (with gym-style shower facilities, locker storage, a towel service) and spaces to cool down and take on some protein after a run. But it will also be brightly decorated and have lifts direct to the main entrance lobby, so runners and riders don’t feel marginalised. ‘When it boils down to it,’ says Badham. ‘It’s the little details that make the difference. ‘Any excuse anyone has not to do exercise, they tend to take it. So you’ve got to make it100 per cent friction free.’

Cook’s research backs this up. ‘For a lot of people considering run-commuting, the issues are that, logistically, it’s very challenging, or it seems very challenging at least,’ he says. But the cultural, emotional and psychological barriers can also be a deterrent. The practical need for access to facilities so you can transition from sweaty, red-faced runner to work-ready mode is important, but confidence, cultural norms and social acceptance play a big part, too. 'An atmosphere of acceptability and a workplace where you can turn up sweaty in Lycra and no one really minds, is essential,’ says Cook. New run-commuters need to know they’re not being judged.

Hannah Beecham, Founder and CEO of RED Together – a 150,000-strong community that empowers people to embrace physical activity to support their mental health – thinks our bosses could hold the key. ‘We’ve done focus groups with PWC, HSBC and Boots employees aspart of RED (Run Every Day) January each year,’ says Beecham. ‘And the resounding thing we always hear is that if their manager is involved, they feel much more relaxed and likely to get involved. If a manager goes out at lunchtime to get active, their employees feel they can take their lunch break [to run]. If the person you’re reporting to embraces it, it sets the tone.’

There are, of course, some people for whom running to work simply isn’t a viable option, either due to the nature of the journey or the nature of their work. Cook’s research also shows that when it comes to galvanising transport, health and sport bodies to concentrate on running, a number of socio-economic and diversity considerations can get in the way, too. ‘There is much less diversity in run-commuting than there is in running,’ says Cook. ‘It’s 90 per cent-plus white and it is higher income groups and males who are doing it. Run-commuters aren’t top priority in terms of the people you perhaps want to have access to active travel or healthy practices. I’m not saying they couldn’t be, but at the minute they’re not.’

For Cain, this is just proof that change is needed. ‘Whatever your age, whatever you physically look like, however you self-identify or what ethnic group you might come from,’ he says, ‘the more people see people of greater diversity and people who look more like them run-commuting, the more they’ll think it is something they can do. And that’s where it begins to become less marginal and more everyday.’

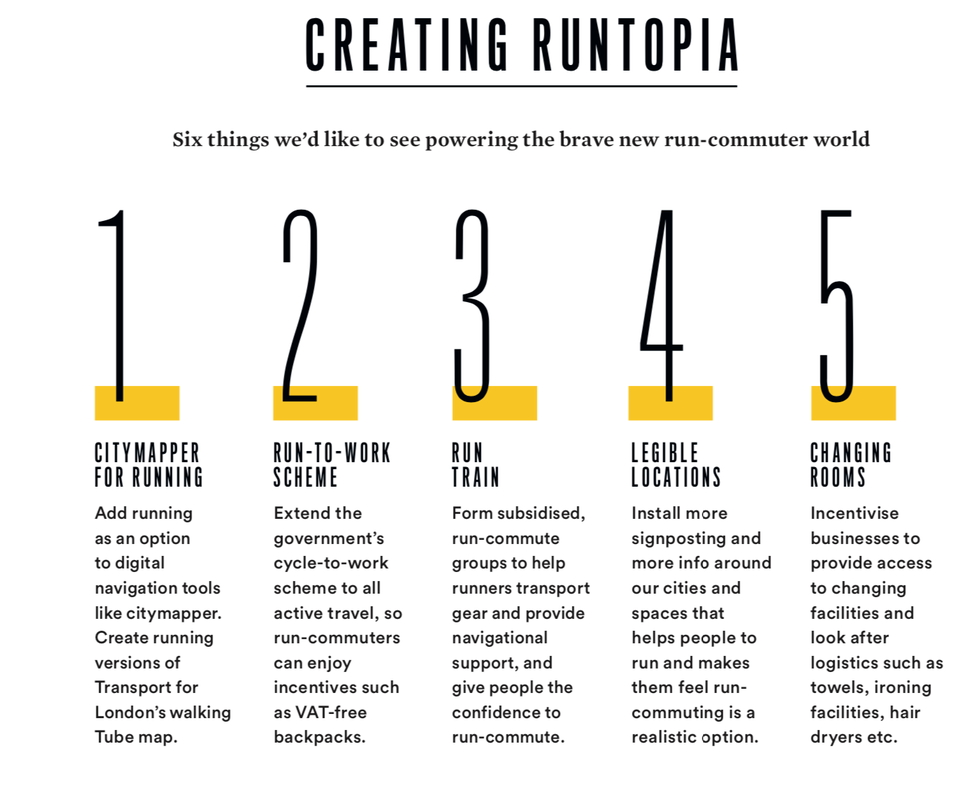

So how do we get to that world where we literally go back to running errands? Nice showers, more run-able streets, more flexible working hours, more run-friendly bosses, better digital tools for route planning might all play a role, but how to make that happen? ‘For me, the biggest thing that could be done is just to discuss run-commuting more,’ says Cook. ‘A lot of people don’t even think about run-commuting as an option. Partly because we don’t think about running as transport, so it’s as much about getting the idea out there that it’s possible, feasible and normal.’

Changing the world could be as simple as doing more of the two things runners love most, running and talking about running. Viva la Run-volution.

#RunSome campaign

Imagine changing your community for the better just by doing more of what you love. No, not eating pizza –we’re talking about running’s potential to transform the planet. That’s why Runner’s World has teamed up with Active Things to launch the #Runsome campaign. We want the running world to unite in a call to arms – and legs – to encourage more people in the UK to run their commutes, errands and other journeys. To get involved, go to Runsome.org, where you can pledge your support, sign up for news updates, find out how to log your run journeys and sign the petition to get the government to recognise running as part of its Active Travel policy alongside cycling and walking. Thanks for being part of the community – and happy running.