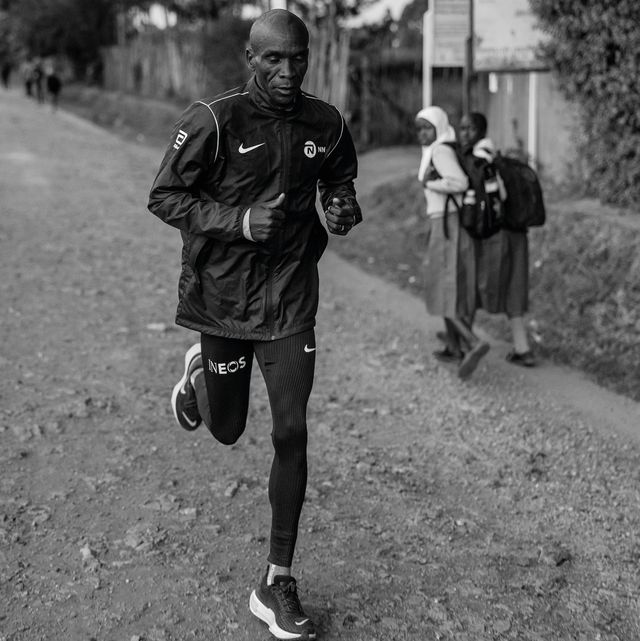

Eliud Kipchoge is the greatest marathon runner ever to lace up a pair of carbon-fibre shoes (or ordinary running shoes, for that matter). Multiple big-city marathon wins, two Olympic Games gold medals, Heart rate training: A runners guide (albeit in a staged, non-eligible event), and the current 42.2km world record-holder. This is a marathon runner who knows how to train.

So when research came out recently that documented Kipchoge’s training, many readers were fascinated, searching painstakingly for the magic formula that makes him the greatest. What secrets might be uncovered and applied to our training to make us faster?

How does Eliud Kipchoge train?

First, there are no secrets. No magic formulas. Second, you’d be ill-advised to mimic the specific content of Kipchoge’s training, given that he’s running 200 to 220km a week – a volume few other humans could get away with. However, we can look behind Kipchoge’s numbers, and identify a couple of key principles that when applied to our training, may make us all better runners.

The first thing that jumps out is how relatively ‘boring’ Kipchoge’s training is. There is a monotony; an abundance of what we might describe as ‘staple’ runs – no bells or whistles, no fancy stuff; he just runs, and accumulates hours and hours of low-intensity training.

And consistency is key. We need to avoid the temptation of tinkering, and rather earn our physiological adaptations through disciplined repetition.

Such repetition goes hand in hand with the second key principle: don’t overdo it. Especially the intensity elements of training. Kipchoge racks up 13 sessions a week, two a day every day except for Sunday, when he takes the afternoon off. But of those 13, 10 are on Thursdays that builds to a fast finishing pace; but everything else is very, very easy – so slow that many club runners would be able to tag along; they range between 4:00 and 5:00 per kilometre.

Which is still quite lively, bearing in mind he’s doing this in Eldoret, at 2,000 metres above sea level. But compare that to his marathon pace of 2:55, and you’ll appreciate just how easy those runs are.

What this means is that Kipchoge gets better at running fast mostly by running slowly.

What are the benefits of running slowly?

There’s physiology behind this – low-intensity training, well within what we call the aerobic training zone, drives adaptations that make us better at endurance running, even when our goal is higher intensity.

The mistake many runners make when they’re aiming to improve is to push too hard too often, as well as not spending enough time in the easiest training zones.

Broadly and most simply, we can divide training into three zones. There is easy training, which is done in Zone 1. At the other end of the spectrum is Zone 3 training, which is what physiologists describe as ‘severe’; once you enter this zone, fatigue is inevitable – it’s a matter of time before the effort becomes too much, and you’re forced to slow down or stop. Think of how you feel during a 5km time trial, or hard intervals. That’s Zone 3.

In between these is Zone 2. This is what we’d call ‘heavy’, but it’s also manageable. You’ll feel like you’re working, and that if you picked the pace up slightly, you’d cross a threshold into Zone 3, where the proverbial bear will jump on your back. But you’re still in control, and you could speed up if you wanted to. You’ll often read about ‘threshold pace’ and ‘tempo runs’ – they fall into this middle zone. See ‘In The Zones’, below, for more on recommended training zones and how to know when you’re hitting each of them.

Why should we spend so little time training at high-intensity?

The way elites train teaches us that in fact, we should spend relatively little time at high intensity. Kipchoge, for instance, spends 85% of his training in Zone 1, and only 15% across Zones 2 and 3. This is a pattern you’ll see in the schedules of almost all the top performers.

The trap that many of us fall into is to allow Zone 1 training to drift up into Zone 2. And I must emphasise, this happens quite easily – push a little hard on a hill, hold that effort over the top, and suddenly a session meant to be an easy recovery day in Zone 1 becomes a moderate day spent half in Zone 1 and half in Zone 2.

Or you’re finishing an easy 8km run, but you feel good; so, 3km from home, you lift the pace just a little, cranking it up progressively, until you finish at around your 10km pace. Over time these efforts accumulate, and your training takes on a 60/30/10 pattern rather than the 85/10/5 of Kipchoge and many other elites.

So what, you say. Well, the problem is that this compromises recovery. If we’re always edging into Zone 2, we get too few days of appropriate aerobic stress. And risk injury and burnout, and dilute our high-intensity efforts – those days when we actually want to push harder – because we’re that little bit fatigued from what was meant to be an easy recovery day, but instead became something tougher.

That’s why Kipchoge spends a lot of his time at a relatively pedestrian 4:30 to 5:00 per kay – it frees him up to really give his hard sessions a proper go. He does those only twice a week: a track session on a Tuesday, and an unstructured fartlek session on a Saturday. There’s a long run Health & Injuries.

How to train like Kipchoge

Train to race – don’t race in training

For practical reasons, we don’t need to completely match Kipchoge’s 85/10/5. Given that we run maybe 50km a week and he runs 200, we don’t suffer the same volume-related stress, so we can afford a little more than 15% higher-intensity training.

For instance, if you were to do two hard sessions (track, hills, 5km time trial) a week, you could quite easily log 10 to 15km in Zones 2 and 3, which would equate to about 20 to 30% of your training. That’s higher than Kipchoge’s numbers; but that’s okay, given our lower total overall running load. The key point is that we must have the discipline to keep that level there, without allowing too many of our easy runs to nudge up into Zone 2.

The moral of the story is a cliché, but it’s true: ‘Train to race – don’t race in training.’ So hold back when you can, in order to go faster when you want to!

How to work out your training zones

Identify your intensity, whether you’re the next Kipchoge or the first you.

Managing training intensity is all about understanding how to identify when you’re moving from a purely aerobic and management training zone into a zone close to your physiological thresholds, and then beyond this into severe exercise. Physiologists have very precise definitions for these boundaries, and various tests can be done and measurements taken to identify what yours are.

But such tests are beyond most people – and honestly, they’re unnecessary, given the range of possible training paces. So instead of being bogged down in the swamp of percentages of VO2 max, If were always edging into Zone 2, we get too few days of appropriate aerobic stress thresholds, here’s a far simpler way to manage your Kipchoge-like training:

If you’re able to hold a conversation in full sentences, without having to interrupt yourself every few words to take a breath, then you’re in Zone 1 – easy training.

If you can talk, but only in broken sentences, then you’re in that middle-threshold zone, Zone 2. (A rule of thumb to follow is ‘10 syllables’ – if you can’t get those out before you need to breathe, then you’re no longer doing a Zone 1 run.)

And then there’s Zone 3, where talking is impossible – and who cares, because the point of Zone 3 is maximum effort. Save your conversations and stories for the finish!

Sleep like your run depends on it

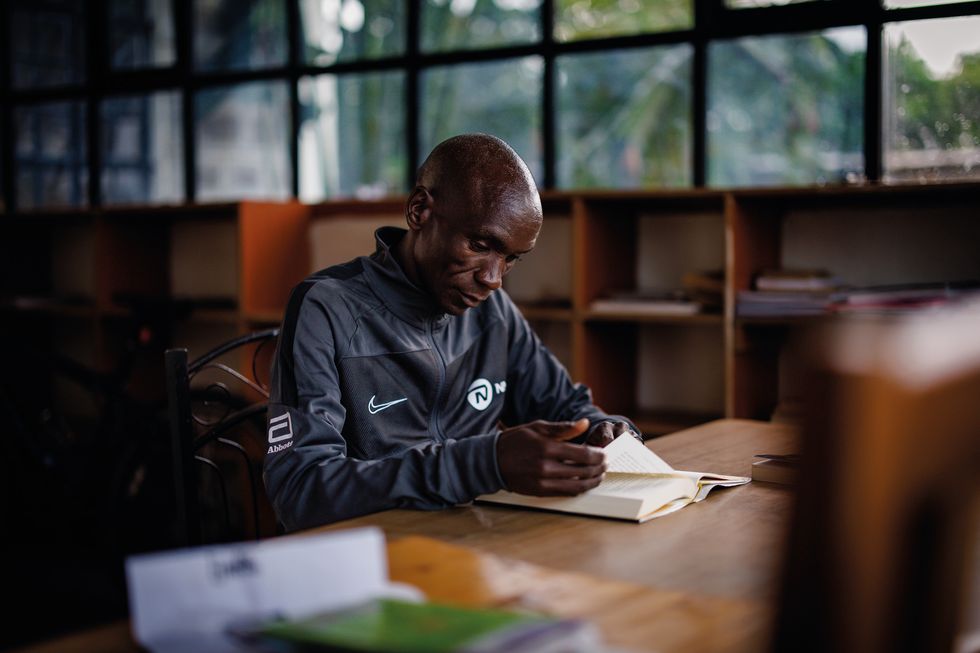

Kipchoge sleeps up to nine hours at night, even after taking up to a two-hour midday nap. Most of us don’t have either the time or 120-mile weekly workload to justify clocking 11 hours of sleep, but we can follow Kipchoge’s sleep hygiene cues.

At least 30 minutes before bed, he turns off all electronics. The habit reduces his exposure to blue light, known to delay the release of melatonin, leading to a decrease in sleepiness, says Kannan Ramar, former president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Then, instead of scrolling through Instagram or Facebook, he winds down by reading at least two chapters of a book.

‘If I have enough sleep, my body and my mind are free of stress and ready to go with the programmes,’ says Kipchoge. While you’re down, your body is doing more than resting. Crucially, your pituitary gland releases growth hormone, which helps your body to grow and repair, says Dr Ramar.

Most runners don’t need a nap if they get the recommended seven to nine hours on a consistent basis, Dr Ramar says. But when you don’t hit that target, naps can help counter – but not completely fix – short-term sleep loss and provide an energy boost for a late-day run, Dr Ramar adds. He suggests a 20-minute nap between midday and 3pm to relieve fatigue. Capping the power nap at 20 minutes will prevent you from entering a deep stage of sleep and feeling groggy after waking, says Dr Ramar.

Revive sore muscles with an ice bath

Twice a week, Kipchoge takes a 10-minute plunge in his camp’s ice baths to aid his post-run recovery. The science behind cold water immersion (CWI) therapy is still being unravelled, but so far it’s promising. ‘Most research shows that, over 48 hours, athletes have reported

What is a good marathon time delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and sometimes corresponding improvements in strength and/or flexibility,’ says Rebecca Stearns, assistant professor of kinesiology at the University of Connecticut, US. Cold water reduces the body’s temperature, which narrows the blood vessels. This flushes metabolic waste from inflammation out of muscles to speed recovery, says Dr Stearns. Water temperature between 10°C and 15°C for 10 to 15 minutes isn’t too uncomfortable and yet cold enough to produce the results, she adds. You can set up an ice bath at home by filling your tub halfway with cold water.

Then, depending on your tap temperature, add ice to bring the temperature down. Dr Sterns suggests trying CWI once or twice a week and checking with your doctor to ensure you don’t have any medical issues that make ice baths unadvisable.

‘It’s very intense,’ says Kipchoge.‘It’s not for everyone. You need to learn to relax and learn to absorb pain.’

Meditate to build mental strength

Kipchoge is an especially mindful runner, says his coach, Patrick Sang. While training and racing, he focuses on his breath and his movements and aims to minimise outside distractions. It’s a skill that helps him embrace the pain and challenges of a marathon.

Mindfulness – a practice of focusing your awareness on the moment with a kind and curious attention and a non-judgemental attitude – can benefit any runner, says Corrie Falcon, director of mindfulness-based training for athletes at the University of San Diego Center for Mindfulness, in the US. Resting your attention on elements of the present moment, such as your breath, heart beat, or even a drip of sweat, can prevent you from getting caught in an inner dialogue mid-training or competition that may unravel your focus.

‘In moments of high stress before or during a race, mindfulness has been shown to reduce the production of stress hormones, reduce blood pressure and heart rate, improve emotional regulation and promote relaxation in the body,’ says neuroscientist and meditation teacher Fhatarah Zinnamon.

Kipchoge credits his focused, spartan lifestyle for developing mindfulness, but it can also be cultivated through a consistent mindfulness routine. Even just 12 minutes of guided meditation five days a week for one month can be effective, says Amishi Jha, a professor of psychology at the University of Miami.

If guided meditation seems outside your comfort zone, Falcon recommends a strategy you can try while running. She describes it as a ‘sense practice’. Run in silence. For two minutes, focus on what you see, then focus on sound, followed by what sensations you feel and then smell. ‘And when you have a thought, label it, “thought” or “thinking” and return to the present-moment experience through the senses,’ Falcon adds.

Upgrade your diet with protein and probiotics

Kipchoge has always maintained a high-carb diet, but after narrowly missing out on breaking the two-hour barrier, running 2:00:25 on the Monza F1 track as part of Nike’s Breaking2 project, he began working with exercise biochemist Armand Bettonviel to improve his nutrition and push his performance. Bettonviel, who develops nutrition plans for elite athletes, sought to up Kipchoge’s protein intake to aid his recovery as well as help to build and maintain lean muscle. ‘I’ve noticed a difference since I started to be serious about nutrition,’ Kipchoge says. ‘Recovery is very fast, I have a lot of energy.’ While the precise detail of Kipchoge’s protein intake is confidential, Bettonviel suggests runners aim for 1.5g to 2g of protein per kilogram of body weight each day.

Kipchoge’s meals feature Kenyan staples such as ugali (corn-flour porridge), potatoes, rice, chapati (wheat flatbread), managu (an iron-rich leafy green), beans, whole-fat milk, eggs, chicken and beef. Meat is only served on about half of the days in the week, so to hit his protein goal, Kipchoge drinks mala, a local sour milk, says Bettonviel. Every 170ml has about 7g of protein, making it comparable to the kefir found in most dairy aisles. Bettonviel also introduced a high-protein porridge to the menu (Kipchoge eats it with fruit after training), made with whey protein and teff, an ancient grain that offers 10g of protein per cooked 180g. You can DIY by mixing half a scoop of protein powder with wholegrain teff

– widely available online – and cook it similarly to porridge.

Build bonus endurance on a bike

For instance, if you were to do two hard sessions track running injury, Kipchoge rides a stationary bike for an hour twice a week after his runs. Cycling is a concentric (shortening) muscle-contraction activity, which is easier for muscles to recover from, says coach Bobby McGee, who has worked with runners and triathletes (including Olympic gold medallist Gwen Jorgensen) for more than three decades. In running, the primary loading is eccentric (lengthening), which is more demanding and damaging. ‘A one-hour endurance run is limited by leg fatigue, not heart and lung fatigue. A two-hour ride doubles the cardio conditioning, but has minimal leg muscle damage,’ says McGee.

Kipchoge spins at an easy pace, which he says also helps reduce muscle soreness. ‘Cycling is a far more effective recovery modality than an easy run, especially for bigger runners with a slower cadence,’ says McGee. You can have too much of a good thing, though: McGee recommends cycling no more than twice weekly and for less than 20% of your overall training time.