Dan Lawson had been running for eight days with barely any sleep, starting at Land’s End in Cornwall, and was now somewhere north of Inverness in Scotland, on his way towards John O’Groats, the most northeasterly tip of mainland Britain. He had got to within about 80 miles of the finish and was on course to break the time he considered the record for running the famous route – the 10 days, two hours and 25 minutes it took Richard Brown to run it in 1995. But for the first time since he started, he began to doubt he could do it.

‘As the light went and the temperature dropped that evening, Dan started to slow,’ recalls Lawson’s coach, Robbie Britton, who accompanied him on a bike almost the entire way. ‘After eight days of relentless motion he was faltering. He didn’t actually look like he could make it. It was partly his body, but also his head. He felt he was running too slow, that he was better off walking, but at walking pace the record just wouldn’t happen.’

Lawson also remembers the wheels coming off. ‘I’d had this nice feeling the whole way,’ says Lawson, ‘this sense that everything was going to be OK. But that evening I just lost it.’

Luckily, his support crew realised the danger and got him to eat a big meal and to have a sleep. ‘He was properly hungry for the first time in the whole trip and we made sure he was full,’ says Britton. ‘Then we all settled down for a three-hour kip.’

‘It was the best sleep I’d had the whole way,’ says Lawson. ‘Afterwards, it was strange, but for about 10 minutes something had gone in my head: I just couldn’t transition from a walk to a run. But then I worked it out, and the nice feeling came back. It was like getting this big hug from the universe.’

In the end he reached the famous signpost at John O’Groats over five hours ahead of his target, running the entire length of Britain in nine days, 21 hours and 14 minutes.

The history of Land’s End To John O’Groats challenges

Ever since brothers John and Robert Naylor completed the first recorded journey on foot from one end of the British mainland to the other in 1871, the idea has captured people’s imaginations. But it wasn’t until 1960 that the challenge became firmly lodged in the British public’s consciousness.

In the first few months of that year, the road between Land’s End and John O’Groats witnessed a frenzy of activity. It all began with eccentric vegan campaigner Dr Barbara Moore, who set off from John O’Groats in early January and walked the route in 23 days, arriving at Land’s End to cheering crowds and television news cameras.

Impressed by Moore’s efforts, the holiday park owner Billy Butlin decided to hold a race along the same route, and so just a few weeks later, on 26 February, 1960, over 700 competitors lined up in John O’Groats ready to take on the challenge, some of them more prepared than others. Butlin had offered generous prize money for the fastest finishers, and the competition was fierce, with lots of cheating uncovered along the way. The majority of the starters dropped out before the end – 150 of them on the first day – and the race was eventually won by Jimmy Musgrave, a 38-year-old glass packer from Doncaster. He collected £1,000 in prize money – enough to buy a house in 1960 – having completed the race in 14 days, 14 hours and 32 minutes, covering more than 60 miles a day. The first woman, a 19-year-old apprentice hairdresser from Liverpool, Wendy Lewis, finished just over two days later and also collected £1,000.

These days, while some, like Lawson and Brown, run it looking to set records, others are in search of a different challenge or do it to raise money for charity, from Ian Botham walking the route to much fanfare in 1985, to the three friends completing the route on skateboards in 21 days, to the man who walked while hitting golf balls the entire way, taking seven weeks.

Since the world went into lockdown and races everywhere were cancelled, the world of ultra running has turned its attention towards what are known as FKTs, or fastest known times. Almost every week there has been a new record set on routes across the country, such as Damian Hall’s FKT on the 268-mile Pennine Way, Sabrina Verjee’s women’s FKT on the same route or Beth Pascall breaking the women’s record on the legendary Bob Graham Round in the Lake District.

Yet few FKTs are as iconic – and, as we’ll discover, as controversial – as Land’s End to John O’ Groats (known as LEJOG, or JOGLE if it’s run the other way around). Carla Molinaro, who in July, just a few weeks before Lawson’s run set a new women’s record on the route, says: ‘At the beginning of lockdown, I realised I had a year totally free [of races], so I looked at a map and thought, there it is, end to end, simple.’

Molinaro said she needed the space of a year without races not so much to train for LEJOG, but to recover from the effort afterwards. ‘I knew it might destroy me,’ she says. In the event she completed the run in 12 days, 30 minutes and 14 seconds, beating the previous record set by Sharon Gayter in 2019. She also beat the 2008 time set by Mimi Anderson, whose book, Beyond Impossible, Few FKTs are as iconic and as controversial as Land’s End to John O’ Groats.

The Long and grinding road

Molinaro may have felt it was going to ‘destroy’ her after seeing what had happened on previous record attempts. As you can imagine, running LEJOG is no picnic. It’s around 840 miles, depending on the exact route you take, with around 30,000ft of elevation, and most of it run on major A roads – often dual carriageways – meaning that as well as fatigue, sleep deprivation, the weather and everything else you would expect to battle through on such a long run, the whole thing is done in close proximity to busy, fast-moving traffic.

In 2019, James Williams set out to break the official Guinness World Record run on the route, set by Andrew Rivett in 2001, of nine days, 2 hours and 26 minutes. He planned to start off running 100 miles a day to give himself some leeway to falter near the end, and he was on schedule for the first few days. But by day five he had been reduced to walking at a pace he says ‘even a snail would be embarrassed by’.

‘I remember crying in a layby along an A-road somewhere in Shropshire,’ he says. ‘I was in such a bad way, and so far from the end, that dropping out was the only obvious choice.’

Despite six months of intensive training, Williams, a 2:30 marathon runner, had run himself into the ground.

The year before, in 2018, Dan Lawson himself had discovered just how tough the challenge was when he made his first attempt to break the record, starting on that occasion in John O’ Groats. ‘I did it that way round as I had this idea in my head that it would be all downhill,’ he says, only half joking. ‘Also, as I live in the south, it would be like I was running home.’

For his 2020 attempt, he says he realised his mistake. ‘The second time I went with the science,’ he explains. ‘Most of the records start in Land’s End because the prevailing wind is south-westerly.’

Lawson is a brilliant athlete, the European 24-hour champion and the record holder in the 145-mile Grand Union Canal Race. But eight days in to his 2018 attempt to break the official Guinness World Record, he says he imploded. Andy Persson, who was running with him around that point, says he looked terrible, his face was all puffed up and he was getting slower and slower. He stopped with just under 200 miles remaining.

The road between Land’s End and John O’ Groats is littered with such tales of physical breakdown. The late Don Ritchie, who Scott Jurek described, in an obituary in the Somehow he carried and set a then-record of 10 days, 15 hours and 25 minutes, as ‘a legend on the roads’ and ‘a very humble, understated badass of the sport’, wrote a detailed account of his record-breaking run in 1989. Describing day five of his attempt, he detailed the state he had by then run himself into: ‘Apart from my bronchitis, and intestinal blood loss, I was now beginning to get stomach pains, despite regular eating. I worried that I might be developing an ulcer. Also the inside of my mouth was very sensitive, almost raw, so it was an effort to eat.’

celebrities who love to run.

All of these tales from this long and winding road make Andrew Rivett’s official Guiness World Record run of just over nine days seem almost unreal. And to many, including Lawson himself, it is.

What is the real Land’s End to John O’Groats record?

When Lawson broke down in 2018 attempting to beat Rivett’s official Guinness World Record, journalist Will Cockerell decided to investigate the little-known Rivett, to find out how he had managed this incredible feat of endurance running. Drilling into the stats and comparing the time to some of the greatest ultrarunning performances in history, Cockerell, a historian and statistician, felt that when you broke it down and analysed it, Rivett’s time topped the lot, and should be considered one of the greatest achievements in sport.

Cockerell wrote a number of articles and blogs on the subject making the point: ‘The world record for 1,000 miles is 10 days and 10 hours by the legendary “Running god” Yiannis Kouros, at a rate of 95.7 miles a day,’ he wrote. ‘It triggered the book, The Six-Day Run of the Century. Rivett ran quicker than Kouros at 96.2 miles a day for only 126 miles less.’

On top of this, Kouros was running around a virtually flat, traffic-free Flushing Meadows park in New York, and he is widely regarded as the greatest ultrarunner in history, with multiple long-standing world records to his name. Rivett, on the other hand, has no other running performances before or since his LEJOG effort to suggest he was capable of outdoing the likes of Lawson and Kouros. Rivett’s best result for a 24-hour race – which he ran four times – is 135 miles. That would leave him trailing 27 miles behind Lawson on his best day, and a whopping 53 miles behind Kouros.

For Cockerell, it just didn’t stack up, so he contacted Guinness World Records about his doubts. However, they replied that after looking into it they saw no clear evidence of malpractice and the record would stand.

Yet Cockerell hasn’t let it lie. He says Guinness’s verification method in 2002 was far from thorough, with Rivett simply needing to get witnesses to sign a logbook saying they saw him go by, and to present photos of him running at various points along the route. ‘If you relate their times to a 100m race,’ says Cockerell, ‘then Dan Lawson is a 9.9-second runner. Rivett’s time, if you do the maths, which was 17 hours faster than Dan’s, is the equivalent of 9.1. It’s intergalactic.’

Cockerell’s conviction that Rivett’s time is somehow a mistake has led him to start a petition to get the record removed from the books. ‘I feel this wonderful event has been stolen,’ he says, explaining why he is persisting so doggedly. ‘I was coaching James Williams and I watched him humiliate himself going for the record. People are hurting themselves trying to beat it. It’s not right.’

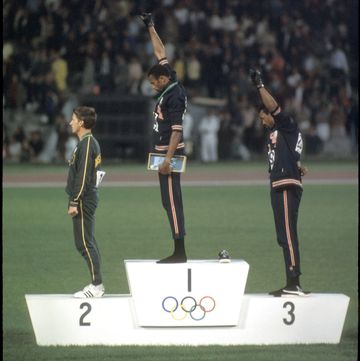

Williams himself is less convinced, however. ‘I'd rather not comment [on Rivett’s record],’ he says. ‘But what I will say is I don't agree that it is impossible to break. It's an amazing time. But then, so are most records. Usain Bolt's 100m time is amazing. But you don't hear many people say it's impossible. Paula Radcliffe's marathon record was amazing, but it was broken. And there are plenty of other examples. With the right training, the right logistics, the right weather, support and lots of other factors, I believe that the record can be broken.’

Through all of the furore, Rivett and his former coach, Ivor Lloyd, have refused to make any comments, although Lloyd says he will be publishing a full account of Rivett’s run ‘in due course’ and, he says, ‘setting the record straight regarding some of the ridiculous and wildly inaccurate allegations made against both of us’.

While Guinness World Records are sticking by Rivett’s time, the official recorder of FKTs for the ultrarunning community, the website fastestknowntime.com, has taken it down and now shows Lawson’s 2020 time as the record.

Lawson says that for his second attempt at LEJOG, he decided to ignore Rivett’s time, and instead try to beat the time he – and most people in the ultra running community – regarded as the real record, set by his friend and mentor Richard Brown in 1995.

‘There was a point near the end,’ says Lawson, ‘when the crew were saying that if we pushed a bit harder, maybe did an extra 15 miles a day, then we could beat it [Rivett’s record]. But I was thinking, “it’s not real”. Trying to beat it, makes it real.’

Lawson says that most of the time he didn’t think about Rivett’s record at all, and the only occasion it got to him was when he was walking around at Land’s End just before the start and saw a picture of Rivett celebrating his run. ‘That made me angry,’ he says. ‘That should have been Richard.’

Dan Lawson isn’t generally a man given to anger, however, and he soon refocused on the higher ideals he hoped to promote with his monumental efforts. Rather than use his run as an opportunity to raise money, Lawson, who runs a community project called ReRun Clothing, that sells, reuses and recycles old running kit, simply asked people not to buy anything while he was out running.

‘Even if people didn’t do it,’ he says, ‘that message hopefully got people thinking, and it fits with the ethos of ReRun, which is about trying to consume less and reduce waste.’ Lawson embodied the message by running the full distance in second-hand clothes and shoes that people had given away, probably thinking their running days were numbered.

Dodging the traffic

Lawson didn’t have to look far for reminders of human impact on the planet on his run. Right from the start, anyone following his run via photos and videos on social media would have noticed how close he was to the traffic. It didn’t look much fun, and couldn’t have made the running easy?

‘For the first hour on the A30 [in Cornwall],’ he says, ‘you’re like, “Woah, this is a bit dicey”. You can feel the wind of the lorries going by, knocking you to the side. But then you get used to it. It just becomes background noise,’ he says. ‘And then, when you get a brief moment when there are no cars, say just for 30 seconds, you really appreciate it. It’s like, “Wow, it’s really beautiful”. It’s almost worth all the noise for those moments of peace.’

Lawson says he was so focused on running the straightest, shortest route, that he would often run straight across roundabouts and junctions without stopping. ‘My crew were telling me to be careful, but I didn’t care, I was just focussed on the finish. Then when I got really tired, I was thinking, well, if I get knocked down, at least it will be a chance to lie down.’

Asked what were the high points of his run, Lawson replies: ‘The whole thing was a high, but the best thing was the people who came out to run with me. Some would just stop their cars and run along for a short while, while others turned up and ran 80km. In some ways the people define the journey more than the landscape even. Best winter running gear.’

Although he didn’t always have the energy to chat back, Lawson says the right people always turned up at the right moment. ‘Sometimes I would just listen to them talking. It was like having a podcast on, people talking to each other and me just grunting. You’re looking forward, so there’s not much eye contact, but you can feel their energy. For example, when I was running through Carlisle one evening, this bodyguard who had done protection work in Iraq ran alongside me, and I just felt safe, protected.’

Molinaro had a similar experience on her record-breaking run, saying that it was the people who came out to join her that made the run so special. ‘Complete strangers kept bringing me cake,’ she says. ‘I didn’t think I’d ever say this, but we ended up having too much cake.’

While she spent the first three nights sleeping in her support van, people following her run online started fundraising to pay for a hotel room for her each night. ‘If there was one within a 10-minute drive of where I stopped, then we went there,’ she says. ‘Just to be able to stand up to change – which I couldn’t in the van – was a luxury. It may have delayed us a little, but having a shower made me feel fresh again and made all the difference.’

On such a long run, there is obviously a lot of eating to be done. Lawson says he tried not to stop moving, picking up his food from his support van and eating it while walking along the road. He says he mostly ate toasted sandwiches, plain pasta and some sports fuel. ‘And always fish and chips at the end of every night.’

Molinaro says she ate every 30 minutes on her run. ‘Not a lot, maybe a quarter of a sandwich,’ she says. ‘I just kept topping up, which worked well, except I got ulcers in my mouth from chewing so much.’

For Lawson the biggest issue was chafing, since the weather was hot and muggy most of the way. ‘There were times when Check out the trailer for. But nothing really worked, as I was sweating so much.’

To attempt to run over 800 miles at any pace requires a lot of training, but to try to break a record like this requires a special level of dedication. For six months prior to his attempt in 2019, Williams got up at 4am every day and ran over 300 miles per week, including 31-mile commutes to work. And that still wasn’t enough.

Williams, who hasn’t given up on his dream to break the record, says the main thing he needs to do before trying it again is to get ‘a lot, lot more experience’.

‘I always knew that I was giving myself a very short amount of time to train for the challenge. And that my experience wasn't where it should be. So, I'll be taking part in a lot more longer distance, multi-day challenges before I make another attempt.’

This is where Lawson had the advantage, as he has been competing as a top ultrarunner for many years. In fact, he didn’t significantly alter his normal training before attempting LEJOG. ‘It’s really hard to train for something like this,’ he says. ‘You just have to have legs conditioned from years of ultra running. You need to be used to feeling terrible.’

He also says that having tried it once, but having failed, really helped him the second time round. ‘It gave me a real determination, not to give up again,’ he says. ‘Charlotte [his partner] and Mick [one of his crew] were there last time, so I couldn’t put them through that again. That was a real driving force.’

After failing on his first attempt, coming back for more is admirable. What about Molinaro, would she do it again? ‘After I finished, I got my crew to film me promising myself I’d never do it again,’ she says. ‘But now, I’m not so sure. I think I could do it quicker!’

Whether it’s Molinaro, Williams, Lawson or others who write them, you can be sure that even without Billy Butlin’s pot of gold, there will be more chapters to come in the story of LEJOG. For some, the lure of history and the clamouring, insistent challenge of our island’s geography will always outweigh the pain – and the traffic. But for now Dan Lawson can give his legs a well-deserved rest and bask in that ‘big hug from the universe’.

Health & Injuries Breaking 10, the excellent film about Dan Lawson's LEJOG run and you can watch the full movie here,